Kamala Harris’s collapse Tuesday evening was shocking to many in the political press, who had expected a tight election but one that, if anything, looked to be trending in her favor heading into Election Day.

There were real — or so it was thought — signs of her impending success, analysts thought. Buoying the wave of assumptions were two polls released over the weekend showing Harris in a dominant position — one, the J. Ann Selzer-run Des Moines Register poll, showed the vice president leading by 3 percentage points in Iowa. Another, from The New York Times and Siena College, showed her ahead slightly in several battleground states, while Donald Trump had a clear lead in just two: Georgia and Arizona.

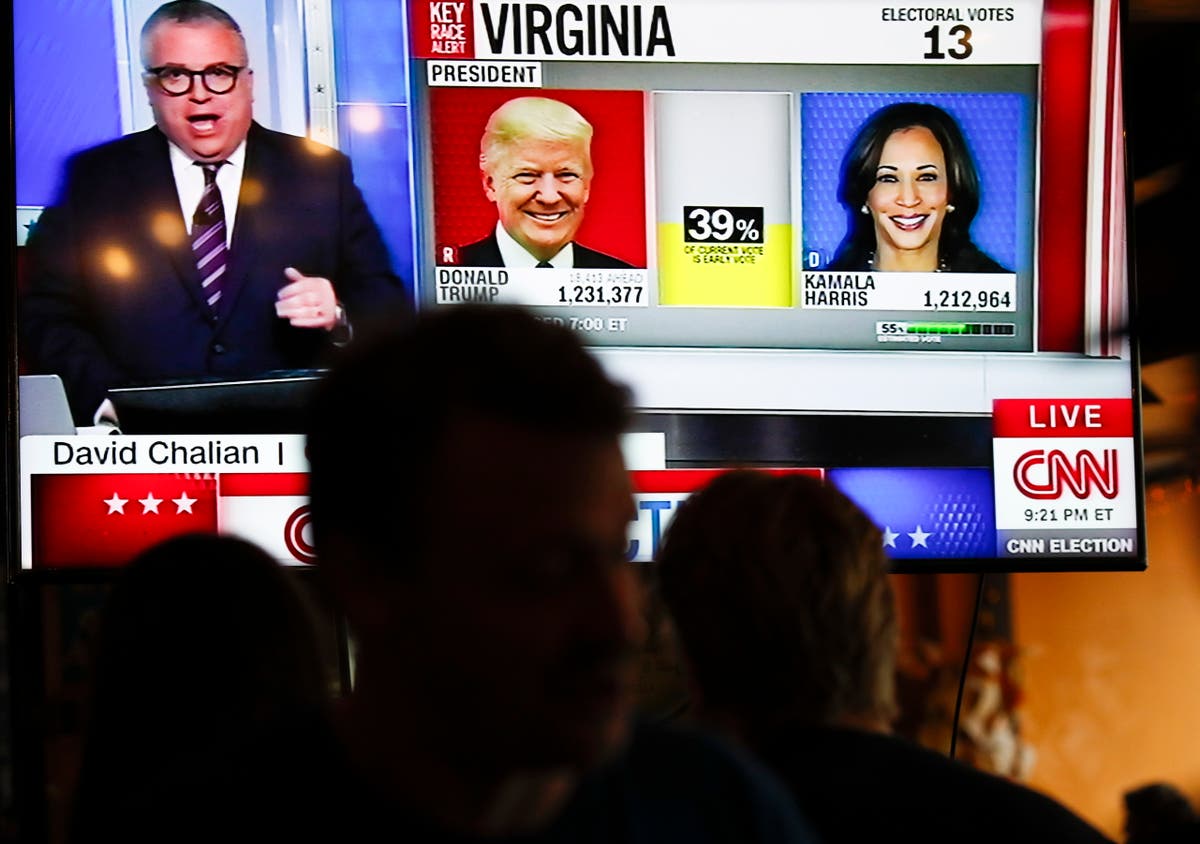

Trump ended up winning both Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, and led in Michigan, Arizona and Nevada as the vice president prepared to concede on Wednesday.

It wasn’t just battleground states where there were gaps between the polling and the actual results. In Maryland, a solidly blue state and the site of a key victory for Democrats in the Senate this cycle, Harris underperformed an average of polls by 1.2 percent while her opponent overperformed his average by 4.1 percent. Unsurprisingly, local polling outfits run out of UMBC and UMD-College Park were the closest to the real results. The Senate race was a similar story: Larry Hogan, the Republican, outperformed every survey of the race, some by quite significant margins.

In New Jersey, another blue bastion, the polling errors were egregious. Just about every poll of the state either widely overestimated or underestimated one candidate’s support. A Rutgers survey in mid-October was off by double digits from Trump’s final percentage; the one October 2-28 ActiVote poll which did get Trump’s final total within the margin of error also had the vice president 6 percentage points higher than her final total.

So what happened? Selzer, whose poll was off by more than 15 points at press time, reflected serenely: “The poll findings we produced for The Des Moines Register and Mediacom did not match what the Iowa electorate ultimately decided in the voting booth today. I’ll be reviewing data from multiple sources with hopes of learning why that happened. And I welcome what that process might teach me.”

The founder of J.L. Partners, one of the few polling firms to accurately predict Donald Trump’s victory in the popular vote, gave a clearer explanation (but an old one) to Newsweek.

“The key thing is people made the same mistakes they did in 2016,” said James Johnson. “They understated the Trump voter who is less likely to be engaged politically, and crucially, more likely to be busy, not spending 20 minutes talking to pollsters… people working a pretty common job or, as the case of many Hispanic voters, juggling two or three jobs at a time.”

Was it underestimating Trump support? Overestimating Democratic turnout? Maybe both of those explanations, at their root, have the same cause: polling firms are increasingly bad at contacting less politically engaged voters. And unlike the talking heads which make up the political media (myself included!), most voters are not highly engaged with politics.

Whichever way those voters skew, politically, is far less likely to be picked up accurately by a pollster. Selzer, for example, famously refuses to contact voters via any method besides a live call — in an age of seemingly nonstop spam calls, it’s a method that just feels inherently dubious.

Whatever the case, it’s clear that some pollsters and, more importantly, the political media needs to get a lot better at talking to low-propensity voters and people who are tuned out from the political news bubble. It’s a challenging prospect, but we risk veering sharply into irrelevance if we don’t.