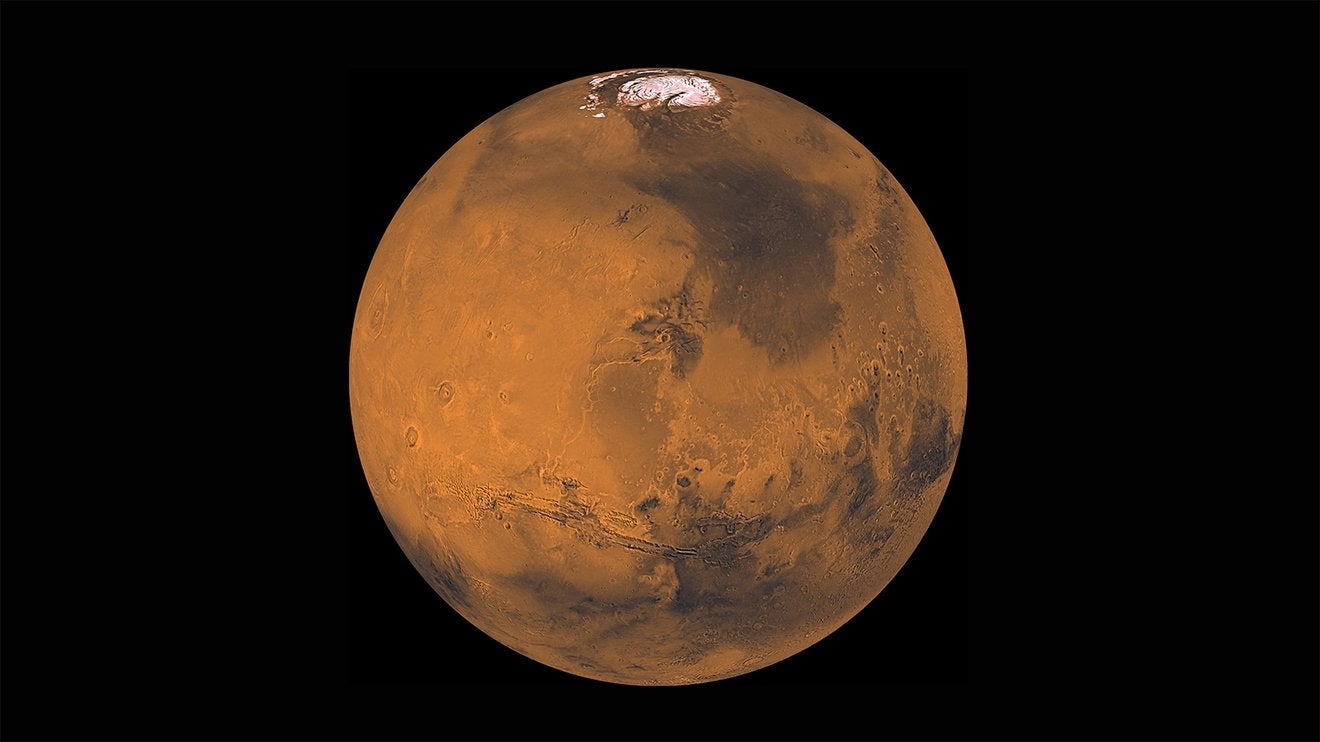

Scientists might have been wrong about perhaps the most obvious thing about Mars: the red colour behind its nickname

Earthlings have known about the existence of Mars, the fourth planet from the sun it also orbits, since ancient times.

Although the celestial body is located 140 million miles away from Earth, there’s a lot that astronomers know about it. For example, it’s a dusty red color.

But, new research from the European Space Agency is challenging humanity’s understanding of why Mars is called the Red Planet.

“Mars is still the Red Planet. It’s just that our understanding of why Mars is red has been transformed,” Adomas Valantinas, a post-doctoral fellow at Brown University, said in a statement.

Valantinas is the lead author of the findings published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

The red dust on Mars is mostly rust, which forms in a similar way to how it does on earth. Known as iron oxide, the material has been broken down and spread across the planet for millions of years by dust storms.

But, the exact chemical make up of the iron oxide has been debated in recent years. Previous observations did not find evidence of water contained within the element.

However, using spacecraft observations and new lab techniques, scientists now say that the red color is better suited to iron oxides that contain water. That mineral is known as ferrihydrite, which forms in the presence of cool water.

“We were trying to create a replica martian dust in the laboratory using different types of iron oxide. We found that ferrihydrite mixed with basalt, a volcanic rock, best fits the minerals seen by spacecraft at Mars,” said Valantinas.

But, because ferrihydrite could only have formed when water was still present on the surface, the researcher said Mars rusted earlier than they previously thought.

“Moreover, the ferrihydrite remains stable under present-day conditions on Mars,” he noted.

The replica Martian dust was created using an advanced grinder, which reduced the dust to the equivalent of one one-hundredth of a human hair. They analyzed the samples using the same techniques as orbiting spacecraft. Data was then used from the agency’s Trace Gas Orbiter, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and rover data to determine particle size and composition to create the right size dust in the lab.

Newly-collected samples will help them to learn more down the line. Although, they may have to wait a few years before they can come back to Earth.

“Some of the samples already collected by NASA’s Perseverance rover and awaiting return to Earth include dust; once we get these precious samples into the lab, we’ll be able to measure exactly how much ferrihydrite the dust contains, and what this means for our understanding of the history of water – and the possibility for life – on Mars,” Colin Wilson, Trace Gas Orbiter and Mars Express project scientist, said.