I’ve been journeying through The National Archives inspired by historian Corinne Fowler’s latest talk with us, about her work ‘Walking through countryside’s forgotten colonial histories’. Collections experts Philippa Hellawell, Elizabeth Haines and Chris Day have joined me to re-enact one of Fowler’s walks – in the archive.

Make sure you’ve read Part 1 and Part 2 of this blog first before reading on.

Ready? This is our final stop. Please note that it refers to violence and dehumanising treatment towards Australia’s Aboriginal peoples.

Third stop: Tolpuddle, Van Diemen’s Land, with Elizabeth Haines

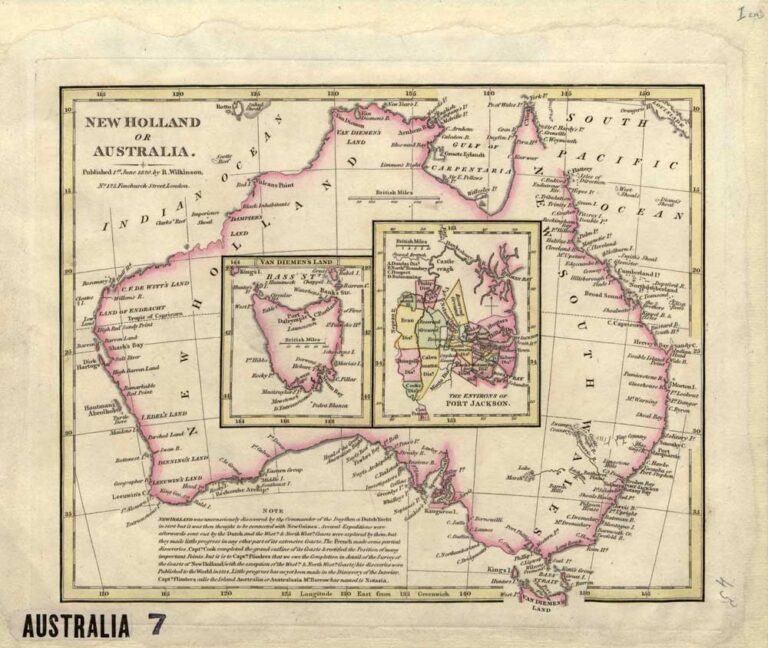

As Chris Day previously explained, five of the six labourers from Tolpuddle were sentenced to be transported to New South Wales. Their leader, George Loveless, was sent to Van Diemen’s Land – known today as Tasmania.

Approaching the end of the walk, we can have a closer look at Van Diemen’s Land and the related colonial records held at The National Archives. I am joined by Dr Elizabeth Haines, specialist in records of the British Empire and Commonwealth. She has chosen two records that speak to the legacy that the creation of the Van Diemen’s Land penal colony had for Aboriginal Tasmanians.

Elizabeth: George Lawless connects Dorset to Van Diemen’s Land through his transportation there in the 1830s. He arrived towards the end of four decades of violence, during which Aboriginal Tasmanians were entirely dispossessed from their lands and livelihoods in order to establish colonial settlements.

It is estimated that in1803, when the British first settled in Tasmania, there were 4,000 to 15,000 Aboriginals (by different accounts). By the time George Lawless arrived on the island as a convict, there were fewer than 400 Aboriginal individuals remaining. During that same period the number of settlers and convicts reached more than 24,000.

This violence, which has been described as genocide, took multiple forms. Aboriginal women and children were stolen into servitude by sealers and stockmen (cattle and sheep herders). Aboriginal communities were fenced out of their traditional hunting grounds and food reserves by farmers. Violence and reprisals followed.

By the late 1820s the British Governor, George Arthur, had declared that those Aboriginal people who resisted colonial rule were ‘open enemies’, who were banished from settled districts and who could be killed without sanction.

Record MPG 1/519 – Map of ‘Military Operations against the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Van Diemen’s Land’, 1831

This map depicts a campaign initiated by Governor Arthur, known as the ‘Black Line’, that took place in October 1830. In this campaign more than 2,000 settlers were recruited to sweep across the island and force all Aborigines southwards into Tasman’s Peninsula. The campaign was very unsuccessful in its stated intent, yet the map remains a powerful visualisation of the processes of dispossession.

At the bottom righthand corner of the map you can see Tasman’s Peninsula, where Arthur hoped to drive the Aboriginals in 1830. The peninsula is not far from where Loveless arrived in Van Diemen’s Land (Hobart) and where he laboured as a convict in Newtown and Glenayr.

It is striking that in the eradication of Aboriginal landscapes, many placenames from Dorset were transposed onto the island including Bridport, Lulworth and Weymouth.

Record CO 280/133 f.171-172 – Colonial Office: Tasmania. Original Correspondence

It is very difficult to find Aboriginal perspectives on this history in our collections, or even any Aboriginal voices from that period. However, in correspondence sent from Tasmania to London in 1841 we have a copy of a request made by Dalrymple Johnson (who was petitioning on behalf of her mother Woretemoeteyenner or Mrs Briggs).

Woretemoeteyenner had been among the 200 remaining Tasmanian Aboriginal people who were forcibly resettled to a ‘camp’, Wybalenna, in 1833. By 1847, only 40 were still living. Dalrymple is petitioning for her mother to leave the camp and join her in Perth, a request that was eventually granted.

A few years after Loveless returned to England, Woretemoeteyenner was reunited with her daughter. However, in Woretemoeteyenner’s journey of thousands of kilometers from Tasmania to Perth, we see the further displacement of Aboriginal families and communities away from their homes and their heritage. The Dorset placenames that can be seen on the map in MPG 1/519, however, remain in Tasmania today.

Surprising connections

Moving between only six records, this journey has allowed us to travel far across time and space, from 17th-century Barbados to late 19th-century Tasmania. Records that speak of injustices and punishments but also (marginal) liberation, who represent the voices of the oppressors but also those, usually silenced, of the oppressed. Records that wouldn’t normally have been brought together when studying history chronologically, but that can surprisingly speak to each other once gathered together, following a walk in the Dorset countryside.

I would like to thank all staff who have kindly helped with this project: historians and collections experts Philippa Hellawell, Elizabeth Haines and Chris Day, who have chosen some walk-inspired records, Karen James who granted access to the repository and retrieved the records, Holly Staynor for the audio recording logistical support and our Blog team for putting this into nice blogposts. Finally, a special thanks to Corinne Fowler whose book and work has been our inspiration.