Inspired by our recent event with historian Corinne Fowler about her work ‘Walking through countryside’s forgotten colonial histories’, I invited collections experts Philippa Hellawell, Elizabeth Haines and Chris Day to join me to re-enact one of Fowler’s walks – in the archive.

If you haven’t already, I suggest joining the walk from its beginning in Part 1 of my blog.

When you’re ready, let’s move on to our next stop…

Second stop: On the way to Tolpuddle, with Chris Day

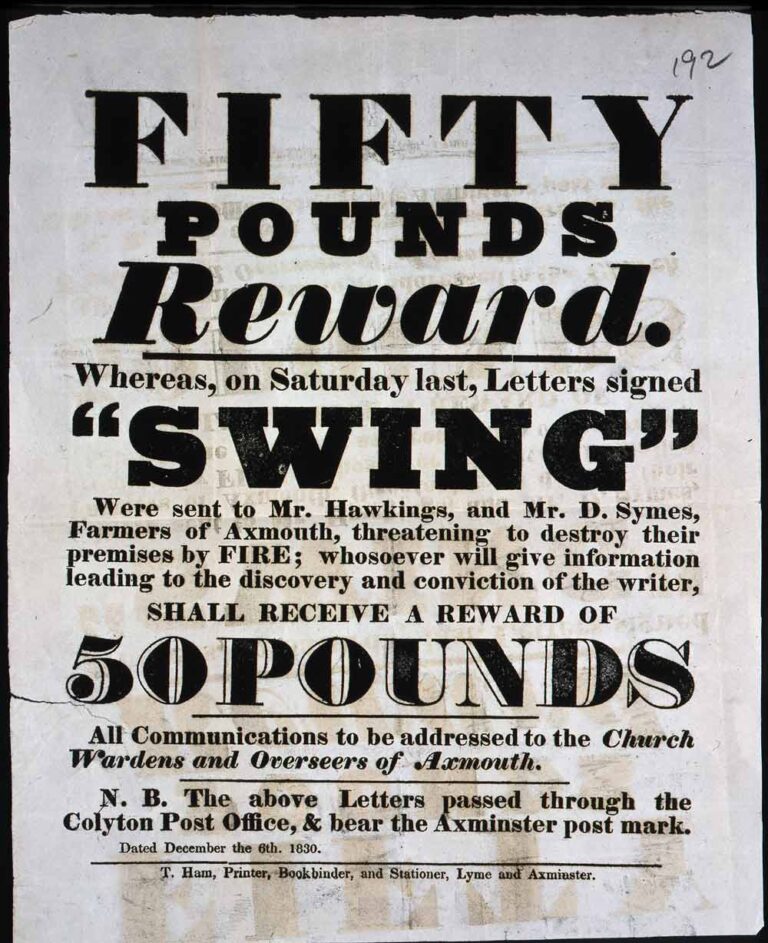

While heading to Tolpuddle, Fowler remembers that following the 1794 Enclosure Acts, social disturbances spread around southern England. This development impacted on labourers’ wages, and along with fluctuations in grain prices and mechanization, led to protests and strikes. Among these were the ‘Swing Riots’ of 1830–1, which saw a wave of arson across Southern England. Suspicion fell on workers often, and they were persecuted.

Until 1824 the ‘combination’ of workers into trade unions had been illegal, a reaction to the threat of the French Revolution. When George Loveless and five other agricultural workers in Dorset decided to form a Friendly Society (a kind of union) in 1833 to organise against their lowering wages, they swore a secret oath, as was traditional.

A local magistrate got wind of this and informed the Home Office. Loveless and his friends were arrested and convicted of swearing unlawful oaths, under an obscure law passed in the wake of a naval mutiny in 1797. They were sentenced to be transported to Australia.

To learn more about the history of the Tolpuddle Martyrs and the birth of trade unionism I’m joined by Chris Day, a historian of 19th-century Britain, who has two records to share.

Record HO 52/24 ff. 53–54 – Counties Correspondence, 1834

Chris: Prior to the late-19th century, Britain had no court of appeal. Clemency and pardons after criminal convictions were a matter for the Royal Prerogative of Mercy, operated by the Home Secretary.

Thousands of people petitioned on behalf of themselves, their loved ones and neighbors, or for people they thought had suffered an injustice, so that they might receive a shorter sentence, a pardon, or be saved from the gallows or transportation.

Immediately after the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ convictions, petitions flooded into the Home Office. The packet containing those relating to James Brine, the Lovelesses, Standfields, and James Hammett contains some 61 separate documents. Included is this letter from the Martyrs’ leader, George Loveless, sent to a supporter and then forwarded to the Home Office.

Record HO 17/24/29 – Criminal Petitions, 1836

Chris: Loveless writes from the coast of Van Diemen’s Land (modern day Tasmania) where he had been transported, separated from his comrades. It had taken 101 days to get there from Portsmouth and he was clearly glad that the arduous journey was behind him, and that he would soon go ashore and be ‘separated from the company I have been in for the last seventeen weeks’. He was, after all, a political prisoner, being treated like a common criminal.

Even across the world, though, Loveless endured persecution and conspiratorial suspicion for his legal trade union activity. He tells how he was examined before Magistrates on his arrival who threatened him with punishment, lest he ‘tell them by what sign the “Trades Union” could assemble in bodies all over the Kingdom at once’, as if they were a revolutionary army. Loveless remains defiant however, telling his supporters, ‘fear not Brother he that is for me is more than all that is against me’.

He was right. Over 800,000 people signed petitions in favour of the Martyrs’ reprieve, and marches and other demonstrations were held for them. They were pardoned in March 1836 and returned to England in the following years.

Finish our walk in Part 3

Come along for the third and final part of our walk, as we stay in Van Diemen’s Land and look for the voices of Aboriginal people from Tasmania in the archive…