In the days before Christmas 1986, a 30-year-old man approached a church in a Manchester suburb seeking safe haven under the ancient “right of sanctuary”.

Viraj Mendis, who had overstayed his visa, feared he would be jailed or even killed if he went back to his home country of Sri Lanka, which was in the grip of civil war.

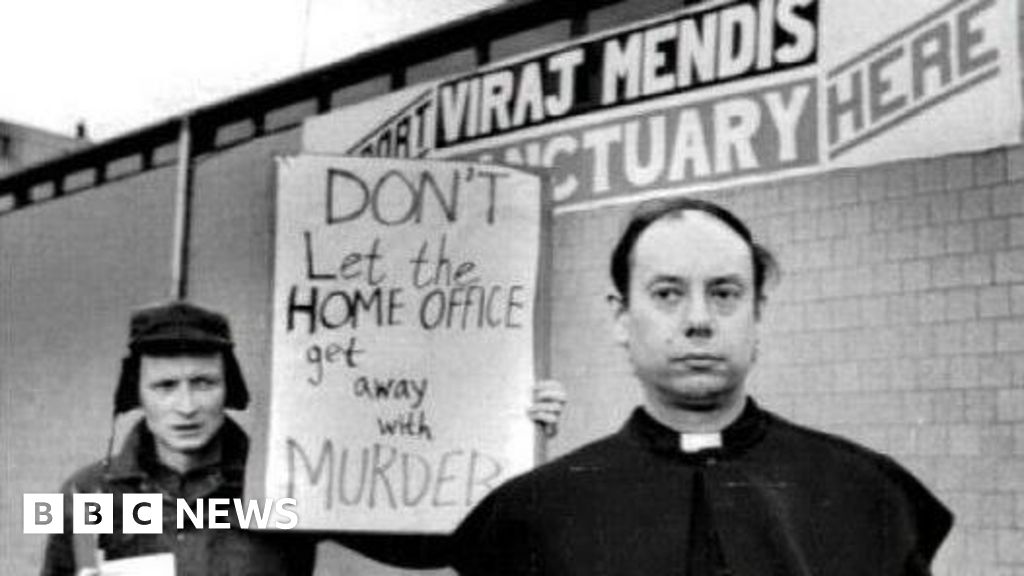

His plea to the Church of the Ascension in Hulme posed a dilemma for its vicar, Father John Methuen, and parish leaders.

The right of sanctuary – which had seen churches provide refuge for fugitives from the law – had long been without any legal force. But for the church, there was a moral and spiritual imperative.

What followed was a stand-off that thrust the church into the international spotlight, pitted members of the community against each other, and culminated in the Home Office storming the church to remove Mendis.

It was a case that sparked widespread debate about the UK’s asylum and immigration policies and human rights – a debate that continues to this day.

“We felt we could not stand by and see him go to probable death without taking a stand for him,” said Fr John.

In Sri Lanka, fighting between the ruling Sinhalese and the minority Tamils was escalating.

Mendis – who had come to Manchester as a student and was active in anti-deportation campaigns – was Sinhalese but he supported the Tamil cause, and claimed this made him a target.

As word about his sanctuary in the church spread, a group called the Viraj Mendis Defence Campaign (VMDC) grew around him.

Members would keep watch over him inside the church 24 hours a day.

He did not leave once in over two years, with meals and clothes brought to him by supporters.

But as the campaign picked up media attention, the risks to Mendis and his supporters increased.

The church received racist phone calls, bomb threats and, only a few months into the sanctuary, a gang attacked it and stabbed a VMDC member.

Chris Procter, who chaired the VMDC, said Mendis’s self-imprisonment took its toll.

“He never went outside. He didn’t have much exercise. He lost weight,” he said.

“So physically, he declined.

“But I don’t think his resolve ever declined at all.”

Over the two years, VMDC members staged marches, and the debate show Kilroy was filmed in the church.

But the vicar’s decision to keep a supporter of the Revolutionary Communist Group in a House of God did not go down well with some locals, nor some members of the Church of England hierarchy or government.

On 18 January 1989, after 760 days, police battered down the doors with sledgehammers and removed Mendis from the vestry.

Tracy Lazard, who was doing her first watch over Mendis at the time, said 100 officers came “just running towards the glass doors and I’m on the other side on a chair on my own”.

“I just started screaming,” she said.

Martin Gaffney, who was a sergeant with Greater Manchester Police, was part of the dawn raid.

“There comes a point where the police, the Home Office have to make a decision and as unpalatable as that might be, it has to be made,” he said

“I have no doubt that our Home Office and various agencies had lots and lots of assurances from Sri Lanka that nothing would actually happen to Viraj when he went back.

“I believed at the time I was doing the right thing.”

Mendis was deported back to Sri Lanka two days later.

Several VMDC supporters flew out to stay with him and protect him, and he would later marry his Mancunian partner Karen while in hiding.

“We had a couple of raids on the house,” she said.

“One day they came into the house, and I hid Viraj in the toilet, and me and my sister-in-law were in there and they came in with their rifle butts.

“They were turning the kids’ beds over. It was absolutely terrifying.”

Mendis believed his case became so well known the Sri Lankan authorities dared not harm him.

He moved to Germany in 1990 and continued to defend and advocate for the rights of refugees.

In one his final interviews before his death on 16 August 2024, featured in the podcast Sanctuary: An Act Of Defiance, Mendis said the “only reason I’m alive is because of the campaign”.

“All I can say is I’m extremely thankful and extremely honoured that they did this,” he said.

- The interview with Mendis was carried out by Ciaran Tracey, who has shared the recording with the .