Donald Trump will return to the White House as the first-ever criminally convicted president after his sentencing in a Manhattan courtroom, where the judge presiding over his criminal hush money trial declined to send him to jail but preserved the jury’s historic verdict against the president-elect.

New York Justice Juan Merchan told the former president on January 10 that “the only lawful sentence” remaining for his crimes is that of an unconditional discharge.

“I wish you godspeed as you serve a second term in office,” he said before leaving the court.

The 30-minute hearing marked a delayed conclusion to the first-ever successful criminal prosecution of a former president, and the only criminal case against Trump to reach a trial.

Trump was forced to attend every day of the proceedings, where he sat with his arms folded, or leaning against the table in front of him, as he stared blankly, shut his eyes, or craned his neck to look at the jury and the witnesses testifying in front of him.

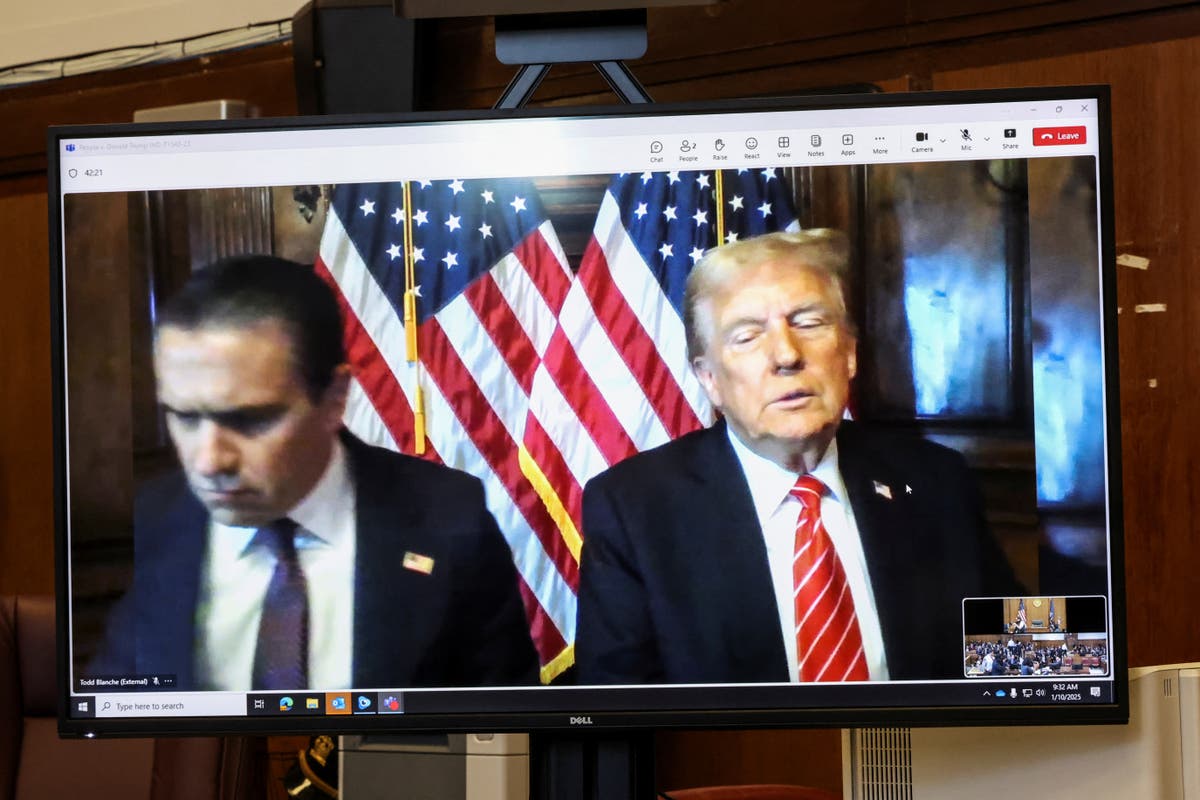

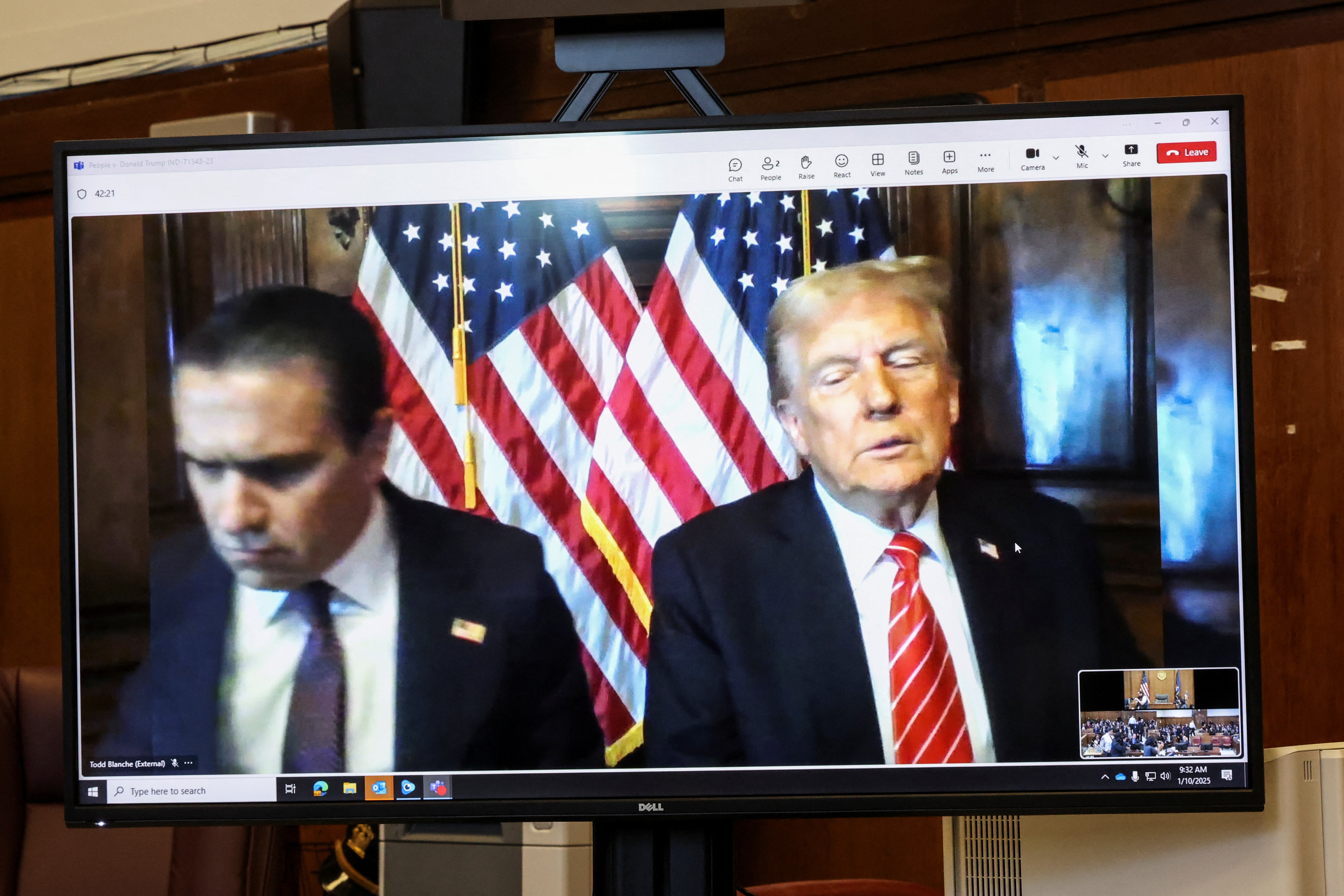

But on January 10, the courthouse once again packed with reporters and lawyers, Trump was nowhere to be seen.

Roughly 12 hours before the hearing, the Supreme Court narrowly declined his demand to pause the proceedings, arguing that his conviction and sentence in the long-running criminal case unconstitutionally interfere with his upcoming presidency.

With all of his options exhausted, Trump had no choice but to endure Merchan’s final decision, securing the first-ever criminal sentencing of a president in U.S. history.

More than seven months after a jury of 12 New Yorkers found Trump guilty of falsifying business records, the president-elect was handed an “unconditional discharge.”

The ruling preserves the jury’s unanimous verdict without any criminal consequences for the president-elect, but he will return to the White House with the stain of 34 felony convictions.

“The sanctity of a jury’s verdict and deference to it is bedrock principle in our nation’s jurisprudence,” prosecutor Joshua Steinglass told the court on Friday.

On May 30, a unanimous jury convicted Trump on all 34 counts of falsifying business records in connection with a scheme to silence adult film star Stormy Daniels, whose story about having sex with Trump threatened to derail his 2016 presidential campaign.

Trump’s then-attorney Michael Cohen paid Daniels $130,000 for the rights to her story; Trump reimbursed Cohen in a series of checks, some of which were cut from the White House.

Those reimbursements were falsely recorded in accounting records as “legal expenses,” fulfilling a conspiracy to unlawfully influence the 2016 presidential election.

Emails, phone records, text messages, invoices, checks with Trump’s Sharpie-inked signature and other documents — including a hand-written note from his accountants that outlined the math for Cohen’s checks — gave jurors the paper trail.

Jurors also heard testimony from former National Enquirer publisher David Pecker, who promised to be the campaign’s “eyes and ears” by using his tabloid to “catch and kill” negative stories about Trump that he never intended to publish. He spent roughly $180,000 purchasing two scandalous stories but refused to spend more by getting involved with Daniels.

Trump’s former White House aide Hope Hicks — who testified to the campaign’s damage control after the release of the so-called Access Hollywood tape — told jurors that Trump did not want the story from Daniels to come out before Election Day.

Cohen — who said he frequently sought approval for his “loyalty” to “the boss” — agreed to pay Daniels out of his own pocket, took out a home line of credit to front the cash, and created a shell company from which he could transfer the funds to Daniels’ attorney.

Trump and Daniels also signed a nondisclosure agreement that blocked her from taking her story public, and her damning testimony in his criminal trial detailed exactly what Trump sought to keep secret, according to prosecutors.

Daniels herself sat just feet away from Trump during her extraordinary testimony recalling a story that Trump spent tens of thousands of dollars trying to stop from becoming public.

She recalled, in detail, the brief but disturbing sex she allegedly had with the former president after a celebrity golf tournament in Lake Tahoe nearly 20 years ago. She was unflappable under cross examination from Trump’s attorneys, who sought to undermine her account and force her to admit she was making it up.

“If that story were untrue, I would have written it to be a lot better,” she said.

After two days of deliberations, the jury’s foreperson quietly replied “guilty” 34 times.

Dramatic courtroom action only played to the reporters and a handful of members of the public who could get inside the courthouse during the weeks-long trial, but the hallways lined with cameras gave Trump a prominent sounding board for campaign speeches to cast himself as a victim of a politically motivated prosecution designed to keep him out of office.

He delivered rambling remarks to reporters in the hallway each day of the trial, and his attorneys drew out flattering depictions of the former president and his business in witness testimony and in their opening and closing statements to jurors.

A trial gag order that blocked him from publicly attacking witnesses and jurors did not stop him from doing so. After he was fined $10,000 and threatened with jailtime, a parade of high-profile allies joined him at the courthouse to attack prosecutors and judges on his behalf.

Trump’s third campaign for the presidency relied on a narrative of political persecution and retribution against a justice system he accuses of conspiring against him.

One month after the jury’s verdict, on the final day of its term, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority issued its landmark decision on presidential “immunity” that Trump has since wielded in attempts to shut down the cases against him.

The Supreme Court’s “immunity” decision partially shields Trump and any other presidents from criminal prosecution for actions considered “official” duties while in office, and provides a presumption of “immunity” for acts in the “outer perimeter” of those “official” duties.

There is no immunity, presumptive or otherwise, for a president’s “unofficial” acts.

Hours after the Supreme Court’s ruling on July 1, Trump’s attorneys argued that evidence used against him at trial should fall under the scope of the high court’s decision.