Congressional investigations and White House threats are “chilling” Palestinian advocacy on Columbia University’s campus, according to lawyers for student activists, who are calling on a federal judge to block their disciplinary records from getting into the hands of Republican lawmakers.

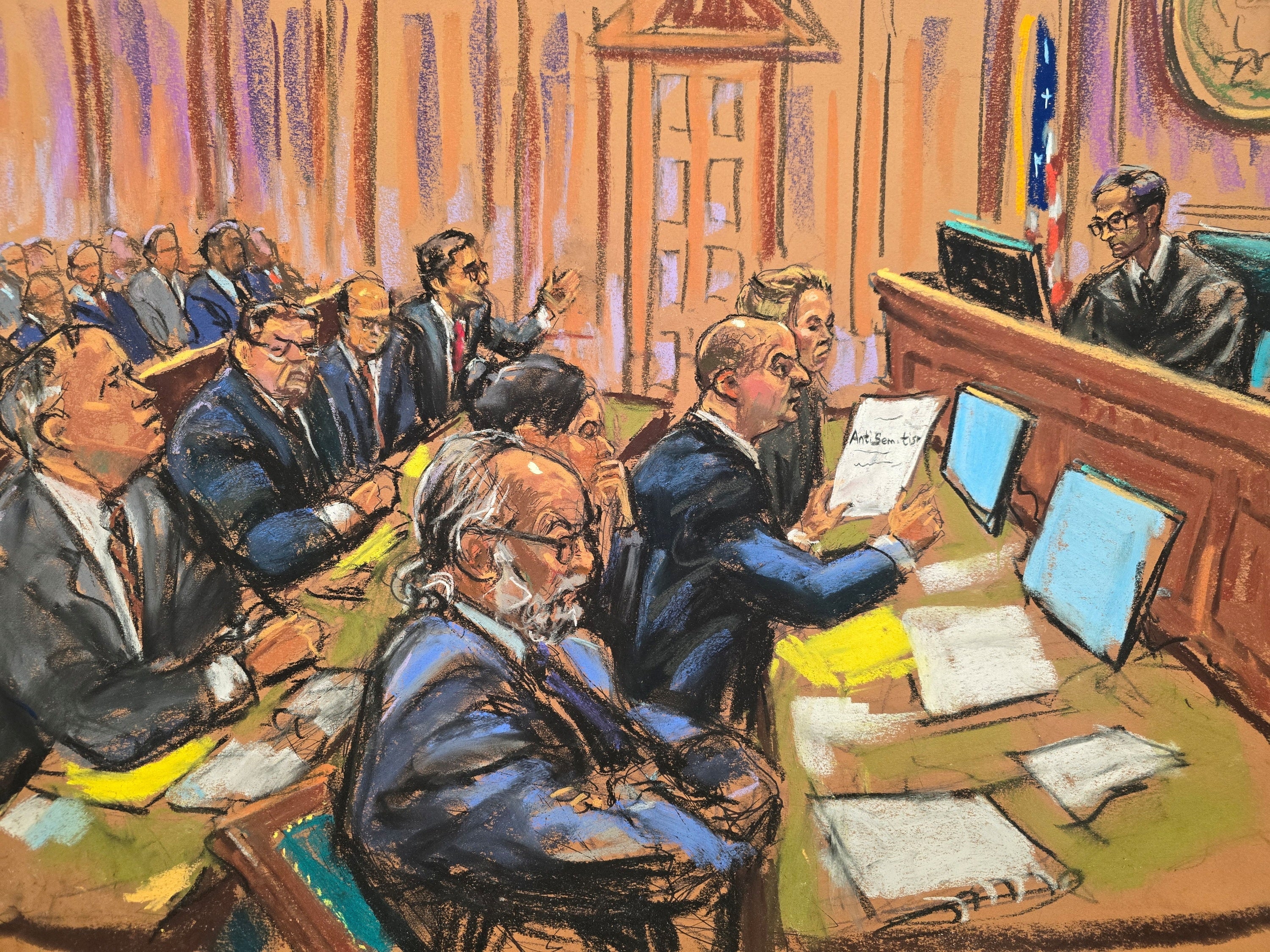

Attorneys for several students — including Mahmoud Khalil, a lawful permanent resident threatened with his removal from the country for supporting campus protests — called on a federal judge in New York City on Tuesday to block the release of those records, fearing they would be used to intimidate, harass and surveil demonstrators in an attempt to suppress campus speech in support of Palestine and against Israel’s ongoing campaign in Gaza.

Student activists are “demonized” for protected speech, according to attorney Amy Greer, who is also representing Khalil in his case against his detention.

“They feel targeted,” she told District Judge Arun Subramanian. “They are frightened when they see their own identities targeted or vilified.”

Last month, the Republican-led House Committee on Education and Workforce demanded that Columbia produce student disciplinary records surrounding campus demonstrations that followed Hamas attacks in Israel on October 7, 2023, and suggested that the school would lose federal funding if it didn’t comply.

House Republicans and Donald Trump’s administration are conflating criticism of Israel with antisemitism and using a “hammer” to “basically repress all speech critical of Israel” while smearing student activists — many of whom are Jewish themselves — as “pro-Hamas” and “anti-American,” Greer said Tuesday.

The hearing came as a separate federal judge in Manhattan blocked the Trump administration from deporting Yunseo Chung, another Columbia student and lawful permanent resident who was the victim of the government’s “shocking overreach,” vilifying her political views and constitutionally protected right to protest, according to her attorneys

Attorney Ramzi Kassem, who represents Chung and Khalil, told reporters outside the courthouse that a temporary restraining order that blocks the government from detaining and deporting Chung is “fair and just.”

“The court did the sensible thing,” he said. “Until further order of the court, [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] will not be able to take further steps to detain her, and we will continue to fight as hard as we need to to vindicate her constitutional rights in court.”

University professors and academic organizations from across the country also filed a lawsuit Tuesday in Massachusetts, alleging the Trump administration is violating the First Amendment through a “climate of fear and repression” on college campuses.

“Out of fear that they might be arrested and deported for lawful expression and association, some noncitizen students and faculty have stopped attending public protests or resigned from campus groups that engage in political advocacy,” according to the lawsuit.

“Others have declined opportunities to publish commentary and scholarship, stopped contributing to classroom discussions, or deleted past work from online databases and websites,” attorneys wrote. “Many now hesitate to address political issues on social media, or even in private texts. The [policy], in other words, is accomplishing its purpose: it is terrorizing students and faculty for their exercise of First Amendment rights in the past, intimidating them from exercising those rights now, and silencing political viewpoints that the government disfavor.”

Greer echoed those arguments in Subramanian’s courtroom.

The actions at Columbia, “coerced” by Republican officials, have had a “profound effect” on student activists, she said.

Shortly after the students’ lawsuit was filed earlier this month, Columbia announced that students involved with the occupation of a campus building last fall now face “multi-year suspensions, temporary degree revocations, and expulsions.”

Columbia also appeared to cede to the Trump administration’s demands for sweeping changes at the university under threat of losing $400 million in federal funds over its “continued inaction in the face of persistent harassment of Jewish students.”

The administration cannot “hold Columbia hostage” for $400 million, Greer said.

Lawyers for Columbia argued that “many” of the actions announced in a statement following Trump’s threats “were the product of months and months of work.”

Asked by the judge whether Columbia would have ever taken those actions without an implicit threat of losing federal funding, Miller called the scenario a “hypothetical.”

“I don’t think it’s a hypothetical,” Judge Subramanian replied.

Miller paused and consulted with another attorney.

“The best way to put it is all actions announced were actions under review and development,” he said.

The letter “crystallized” Columbia’s efforts and the timing for announcing them, according to Miller.

Lawyers for the committee denied that its February letter to Columbia presented any threat. The university has already delivered the committee a “sizable amount” of information that is under review, but it remains unclear what the committee plans to do with it.

All of that information has been anonymized, according to attorneys for Columbia and the committee.

But students at Columbia are “some of the most surveilled people in the country right now,” Greer said.

Even if the information is anonymized, by placing the students in certain times and places, “somebody is going to recognize that,” said Greer, noting pressure from pro-Israel groups like Betar and Canary Mission that have launched social media campaigns targeting activists.

Department of Justice lawyer Harry Graver argued that the actions at the center of the letters to the university “have nothing to do with protected speech” and are instead “unlawful conduct.”

“This is about antisemitic harassment and violence,” he said.