No one has ever made a good movie,” said Robert Altman. He had, of course, made a dozen or so great ones himself – Nashville, M*A*S*H, Gosford Park among them – and many others that are, by most metrics, good. What the Oscar-winning filmmaker meant, he later explained, is that cinema as he saw it was indebted to other artforms; that, at that time in the 1970s, cinema had yet to step out of the trappings of theatre and become its own inimitable thing.

And yet, Altman’s oeuvre is as purely cinematic as they come. His films – often ensemble-led patchworks of American life – were singular and forward-looking, imposing his signature style onto genres as diverse as antiwar satires, detective noirs, psychological thrillers, and westerns. He was an independent filmmaker through and through – one with a company of first-rate, idiosyncratic collaborators and a near-mystical ability to get an unlikely project financed; The New York Times once branded him the “pirate king of American filmmaking”. Altman died in 2006, and would have turned 100 this month. His influence, though, continues to be seen in many of the best American films of today.

Compared with some of the other filmmakers to emerge from the New Hollywood revolution, however, Altman is relatively underappreciated. M*A*S*H* (1970) – his breakthrough film and a commercial success he would never quite replicate – gave him some level of celebrity at a time when filmmakers were just starting to achieve the sort of profile only previously afforded to stars. But it wouldn’t last, and while contemporaries such as Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese remain iron-clad household names, Robert Altman is a name only really spoken by cinephiles.

Age may well be a factor: Altman was 20 years the senior of many New Hollywood filmmakers, the Scorseses and Spielbergs who have continued making popular films well into the 21st century. But this age differential is also what set him apart from many of his peers. His films were humanist and world-wise; they were, almost always, films for adults. Before M*A*S*H, Altman – who’d been a bomber pilot during World War II – had enjoyed a few early forays into the film industry (a script credit on the 1948 noir Bodyguard; a James Dean documentary and his obscure drama debut The Delinquents in 1957), but had mostly cut his teeth working on industrial films and TV shows, as well as directing theatre.

He was far from the only director to get his start in this way (Spielberg famously made his debut on an episode of Columbo), nor did he award it any undue significance: in later years, he credited his time in television with teaching him the technical fundamentals while producing little of creative note.

But these early years, in many ways, laid out the blueprint for what followed. It’s noteworthy that Alfred Hitchcock spotted something in him, hiring him to direct two episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents in the mid-fifties. Altman’s work on industrial films saw him experiment with unconventional sound mixes – including the naturalistic “overlapping dialogue” that would later become his signature. Meanwhile, his work as a theatre director would inform much of his mid-career period, when, in the Eighties, he started adapting stage plays for the screen.

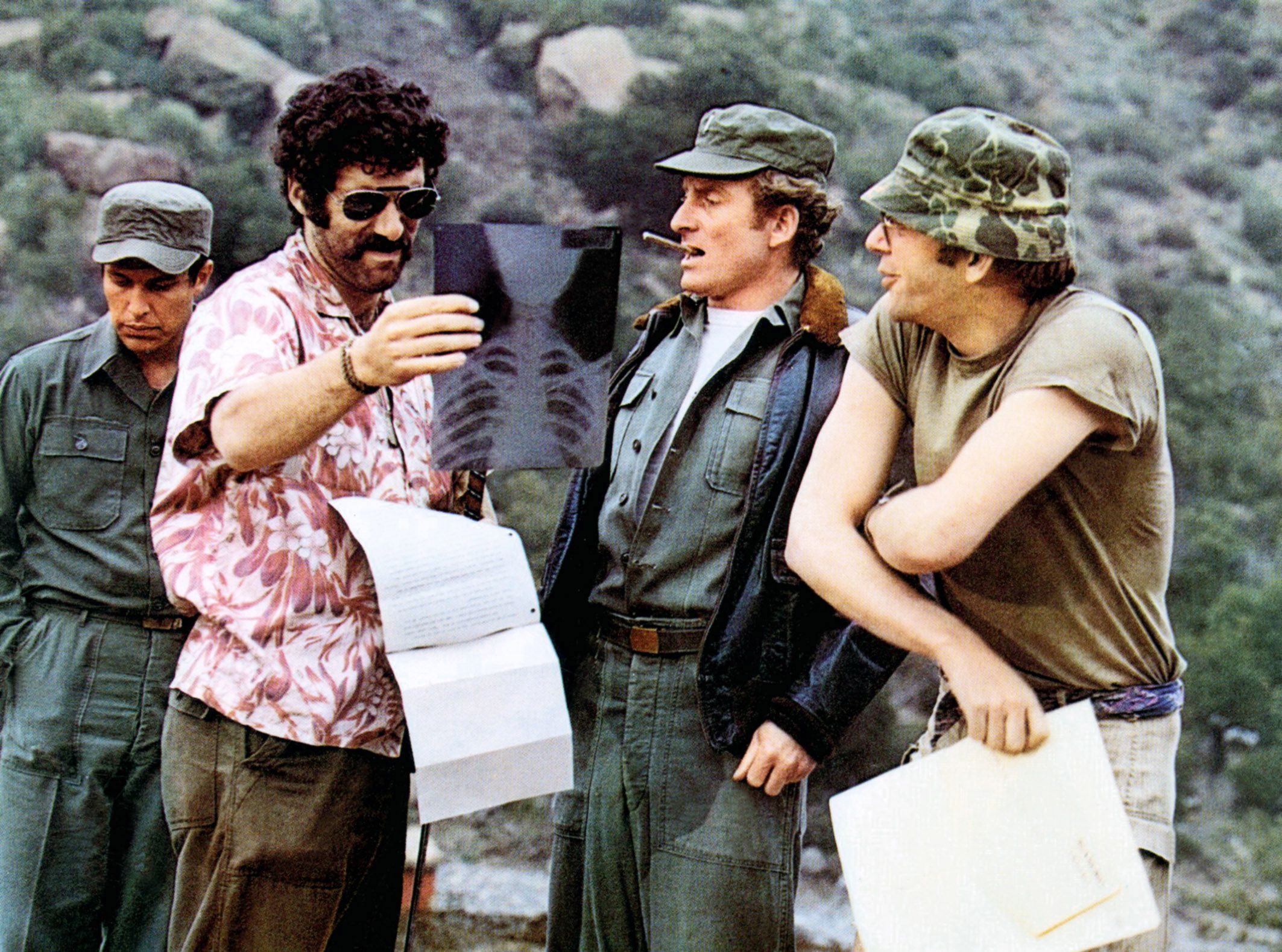

When he did make the jump to films in earnest, it was a rocky transition. He was fired from the 1967 sci-fi Countdown after filming was complete: studio executives baulked at the overlapping dialogue, believing it to be technical incompetence on his part. His next film, the psychological drama That Cold Day in the Park, did at least see Altman complete the project, but reviews were mostly damning. Then, in 1970, came M*A*S*H. An irreverent war dramedy starring Donald Sutherland, Tom Skerritt, and Elliott Gould, M*A*S*H satirised the Vietnam war through the lens of the Korean one. Several directors had turned down the project before it fell at Altman’s feet; no doubt they later regretted it.

The decade that followed this produced one of the all-time great directorial runs. McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971), which starred Warren Beatty as an enterprising gambler and Julie Christie as a brothel madam, has endured as one of the finest revisionist westerns ever made; The Long Goodbye (1973), a languid take on noir starring Gould (a frequent Altman collaborator) as Philip Marlowe, is likewise revered within its own genre. Nashville, a slow, sprawling look at the US country music scene, is a work of staggering social, political and emotional depth. What’s more, it took Altman’s ensemble-cast ethos – the eschewing of a protagonist in favour of a web of interweaving supporting characters – to new heights.

Those films – plus the dark, disturbing 3 Women (1977) – may be the most well-known of Altman’s Seventies trove, but there’s gold, too, in the margins: the bizarre, ambitious Brewster McCloud (1970), for instance, in which Bud Cort attempts to fly using mechanical wings, or the hypnotically watchable gambling drama California Split (1974), another Gould-fronted venture. All films were different, but all immediately identifiable as his handiwork – as much as, say, a Wes Anderson film might be today. “Once [Altman’s style] is understood, it can be recognised in almost any one part of any film he makes,” wrote Robert Kolker in A Cinema of Loneliness. “He stands with [Stanley] Kubrick as one of the few American filmmakers to confirm the fragile legitimacy of the auteur theory with such a visible expression of coherence in his work.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

That golden run – and indeed Altman’s standing in the film industry at large – hit a roadblock in 1980, with the release of Popeye. The film, a musical adaptation of the classic nautical cartoons, starring Robin Williams as the spinach-gulping strongman, was a tricky proposition: Altman’s predilection for muffled, authentic dialogue went against the very fundamentals of screen musicals. Though it has now been reappraised by many critics and fans of Altman, Popeye was, at the time, a disaster, and the 1980s saw the director assume a markedly lower profile in Hollywood.

It would be wrong, though, to attribute this solely to Popeye. Even at the peak of his powers, Altman’s uncommercial, independent-minded films were not an easy sell for many studio executives; when negotiating a deal for a movie in the late 1970s, Altman was told by an exec that “we don’t want this to seem too much like a Robert Altman movie”. His 1980 film HealtH was produced as part of a multi-film deal with Fox, but the studio refused to distribute it; Altman ended up taking it to screen at colleges and festivals himself.

In the doldrums, he remained prolific, even if most of his 1980s films are dimly remembered. He increasingly turned back to the small screen, for TV movies and the 1988 political mockumentary miniseries Tanner ’88. Then, in 1992, film-industry satire The Player catapulted him back into the affections of the industry and the public. The following year, Short Cuts – a brilliant adaptation of several Raymond Carver short stories – proved it wasn’t a fluke. And while the final stretch of Altman’s career may have had a few misses, he went out on a resounding high: Gosford Park (2001), a period murder mystery, is among his most acclaimed films, while A Prairie Home Companion (2006), his final film, was a fittingly sophisticated meditation on death.

For the making of A Prairie Home Companion, Altman was shadowed by the filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson, who was hired as a standby director should Altman die during production. This in itself was testament to Altman’s hallowed-elder-statesman status at the time: the fact that one of Hollywood’s buzziest young filmmakers would be willing to simply play backup. Of course, Altman carried particular weight with Anderson; Altman’s creative influence is all over Anderson’s early work, particularly the ensemble-led LA odyssey Magnolia (1999), and the electric porn-star drama Boogie Nights (1997).

Anderson’s films – including the elegiac stoner noir Inherent Vice and the thorny age-gap romance Licorice Pizza – are among the best modern films to pull from Altman’s bag of tricks. But the vestiges of Altman’s style can be seen everywhere these days, in films such as Knives Out, The Big Short, even The Menu – or any of the ensemble-led works of Wes Anderson. Indie drama Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point, a quiet contender for one of the best films of 2024, is thoroughly Altmanesque.

This legacy extends, too, beyond just movies, and into some of the finest television around. HBO western Deadwood, one of the very best TV shows ever made, would not exist without McCabe & Mrs Miller; Altmanesque touches can be seen in The Wire and, more recently, in Nathan Fielder’s phenomenal The Curse. Altman may have had an on-and-off relationship with TV himself, but it wouldn’t be quite the same without him.

It may still be true that no one has “made a good movie”, in the sense that Altman meant it – perhaps, outside of the experimental sphere, cinema will always be indebted to other artforms: to theatre, and music, and visual art. But this doesn’t matter. Altman’s films were themselves rich in music and a sense of theatre – and boy, were they good.