A pensioner who has spent nearly 40 years behind bars has had his murder conviction overturned in what’s thought to be the longest-running miscarriage of justice in British history.

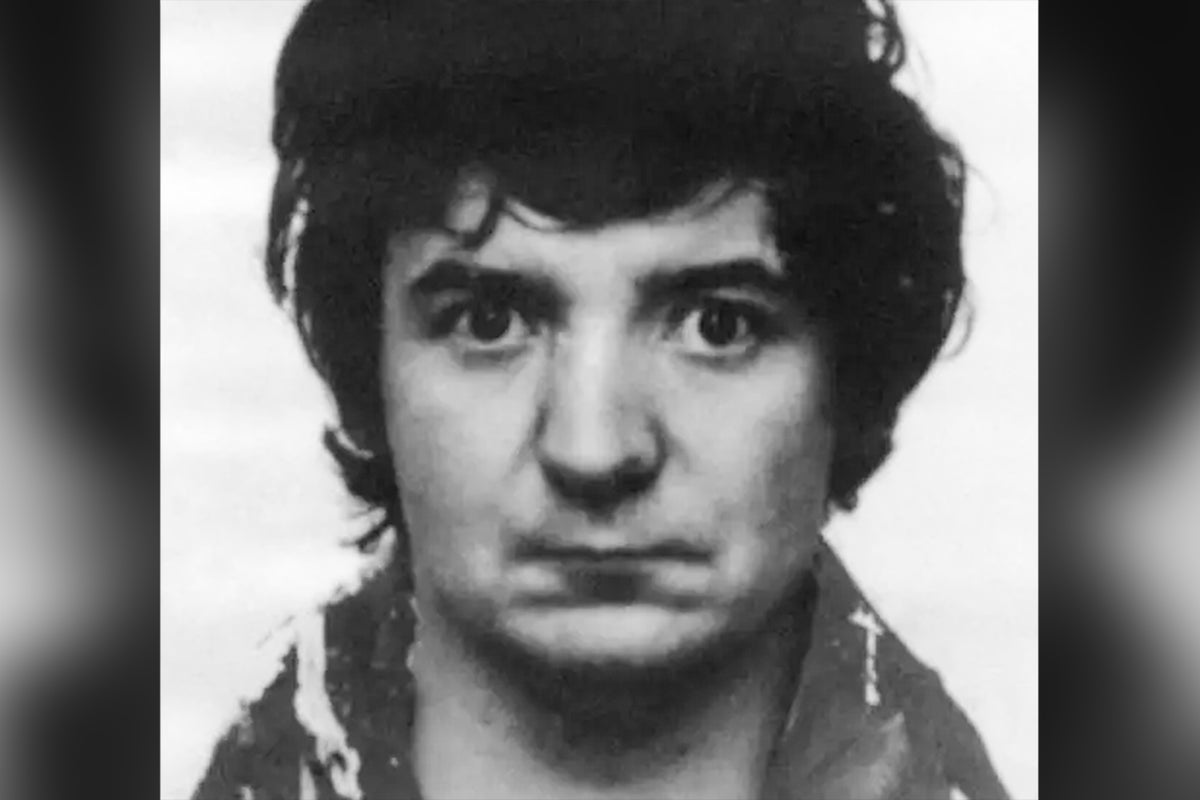

Peter Sullivan was convicted of murdering Diane Sindall in Bebington, near Merseyside, in August 1986, but new tests revealed his DNA was not present in samples preserved from the crime scene.

Now aged 68, he has served 38 years in prison and has previously tried to overturn his conviction twice, over concerns around analysis of bite marks and the manner in which his police interviews were conducted.

Sullivan appealed against his conviction for a third time – 17 years after his first attempt to overturn it – after the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) referred his case to the Court of Appeal.

As the decision was given, Mr Sullivan, who attended the hearing via videolink from HMP Wakefield, held his hand to his mouth and appeared tearful while members of his family embraced.

A part-time florist and barmaid, Ms Sindall was brutally raped and murdered after she had finished a shift at the pub. The 21-year-old, who was engaged to be married, had started walking to a petrol station after her van had broken down when she met her attacker.

She was beaten to death, with her body left partially clothed and mutilated in a “frenzied” assault. Some of her belongings were later found burnt in woodland on Bidston Hill, about five miles away.

Semen which was discovered on her abdomen had been partly diluted by rainfall, and therefore had not been possible to test until 2024.

It was alleged during his 1987 trial that Mr Sullivan had spent the day drinking heavily after losing a darts match, and had armed himself with a crowbar before a chance encounter with Miss Sindall.

Mr Sullivan, who was aged 29 at the time, initially denied the attack but later signed a confession, but has since maintained his innocence. He was convicted on the basis of his retracted admission, circumstantial evidence around his whereabouts, and the assertion that a bite mark appeared to match his teeth.

He was jailed for life and has remained behind bars, despite being handed a minimum term of 16 years.

In November the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) said that Sullivan’s conviction had been referred to the Court of Appeal on the basis of DNA evidence.

Samples taken at the time of the murder were re-examined and a DNA profile that did not match Sullivan was found, the commission said.

Sullivan applied to the body to have his case re-examined in 2021, raising concerns about police interviews, bite mark evidence and the murder weapon.

He claimed he had not been provided with an appropriate adult during interviews and was initially denied legal representation.

Speaking to the court, his barrister Jason Pitter KC said that Mr Sullivan was “mentally handicapped” and a well-known fantasist, and gave “blatantly wrong answers and inconsistencies” when questioned.

“To summarise, the appellant was extremely vulnerable in an interrogative situation, because of his limited intellectual functioning, combined with his problems with self-expression, his disposition to acquiesce, to yield, to be influenced, manipulated and controlled and his internal pressure to speak without reflection and his tendency to engage in make-believe to an extreme extent.”

He continued: “What he was saying was nonsense, in plain terms.”

In written submissions for the hearing on Tuesday, the CPS said the new DNA evidence is “reliable” and that it “does not seek to argue that this evidence is not capable of undermining the safety of Mr Sullivan’s conviction”.

Duncan Atkinson KC, for the CPS, said: “The respondent considers that there is no credible basis on which the appeal can be opposed, solely by reference to the DNA evidence.

“On the contrary, the DNA evidence provides a clear and uncontroverted basis to suggest that another person was responsible for both the sexual assault and the murder.

“As such, it positively undermines the circumstantial case against Mr Sullivan as identified at the time both of his trial and his 2021 appeal.”

He added: “Had this DNA evidence been available at the time a decision was taken to prosecute, it is difficult to see how a decision to prosecute could have been made.”

When asked by one of the three judges overseeing the appeal, Mr Justice Goss, whether he could conceive of a basis on which Sullivan would have been prosecuted if the DNA evidence was available at the time, Mr Atkinson replied: “No.”