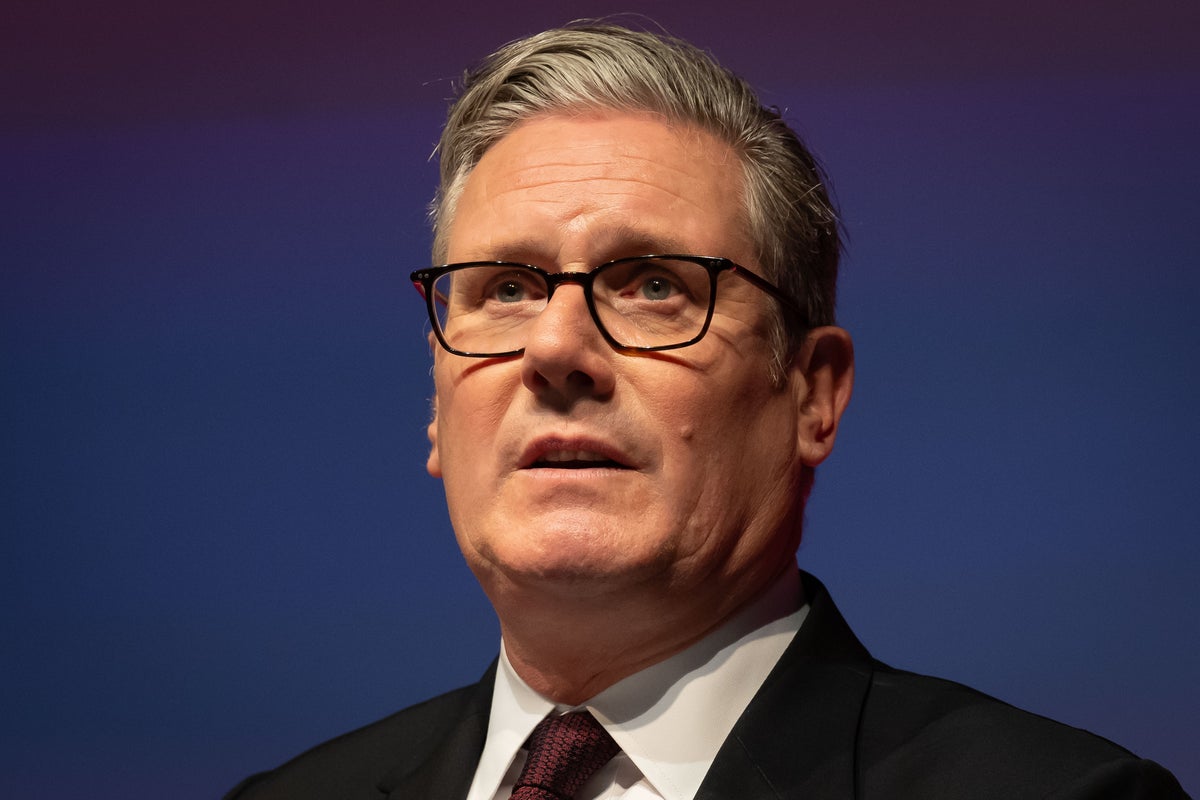

Divided parties do not win elections, and yet Labour cannot help itself. The damage done to Keir Starmer by the rebellion over welfare changes is not just the number of MPs who vote against the Labour whip today, but the revelation that so much of the party is in a state of boiling resentment against its own government.

It is not just MPs. Andy Burnham and Sadiq Khan, the two elected Labour politicians with the largest democratic mandates of their own, oppose the disability benefits bill. And Survation polls of Labour members reveal that they rate Rachel Reeves, Liz Kendall and Keir Starmer – the architects of the welfare changes – lowest among cabinet ministers.

Two-thirds of them think the party should “move to the left”, and more want a change of leadership before the next election (42 per cent) than want Starmer to stay on (40 per cent).

Of course, there is a legitimate debate about the welfare bill. Kendall has not made her case well, allowing the changes to appear to be purely Treasury-driven. And the leaders of the Labour rebellion sought to be constructive, making their representations in private.

The prime minister has undoubtedly bungled his response, saying: “I’m putting this as context rather than an excuse: I was heavily focused on what was happening with Nato and the Middle East all weekend.” Even as an excuse, this is thin – the rebels alerted the chief whip weeks and weeks ago.

But there are bigger issues at stake. The rising cost of disability benefits is a genuine problem that needs to be solved. The government may not be going about it the right way, but the rebels seem to give the impression that they think more public spending is always the answer.

If the government and the rebels were engaged in a genuine negotiation, they would be looking at the Channel 4 documentary made by Fraser Nelson, the former editor of The Spectator, which described the incentives for assessors to grant personal independence payments (PIP). Instead of crudely cutting eligibility, the government should be focused on making the existing system work as intended.

Where are the ministers making this case? Where is Angela Rayner, the deputy prime minister? Should she not be rallying behind Starmer, explaining to Labour MPs and party members that when they signed up for difficult decisions, this is what it meant?

Where is Rachel Reeves, the iron chancellor who models herself on Gordon Brown? Brown, for all his flaws, saw welfare as part of his policy empire and sought to make the argument for reforms to get people off benefits and into work.

Instead, we have the Labour Party tail wagging the government dog.

Starmer has U-turned at a cost of £2.5bn a year by the end of parliament, wiping out half the original savings, which means the welfare budget is going to continue to rise – not as fast as originally forecast, but faster than Reeves hoped when the changes were first announced in March.

The outcome will please no one and make the prime minister look weak. Meanwhile, the rebellion has drawn attention to the reality that a large number of Labour MPs, leading elected Labour politicians outside parliament and the majority of party members, oppose the government across a range of policies.

How long can a party function in permanent opposition to itself?

Labour members can see the danger. That Survation poll for Labour List finds that 72 per cent of them say that Nigel Farage’s Reform party is “Labour’s biggest electoral threat”. Yet, they appear to think that the way to meet this threat is to increase further spending on disability benefits that most voters already think is too high, and to make it obvious to the electorate that the party is in a state of civil war.