Two old men sit in a small kitchen in Kensington, both in their eighties. They are making the final plans for a blockbuster exhibition in Paris, sharing their passion for art like teenagers.

“It’s going to be stunning,” says David Hockney, 87, still a fighting force in a wheelchair, a nurse by his side. He is chatting with the legendary curator Sir Norman Rosenthal, 80, a bit wobbly himself and recovering from cancer. Both, however, have minds that crackle with wit, wonder and vim.

Rosenthal, who has spent two years curating the show, riffs: “Beautiful and important, this is the most extraordinary gathering of Hockneys for a generation.” Just a week before the public sees it, they are sorting the final details of the artist’s biggest show of the last 25 years: “21st century Hockney.”

“My friends call me Lucky Norman and curating this show just proves they are right,” says Rosenthal, gathering his final thoughts before heading to the Eurostar ahead of its opening.

In a sporty white shirt, hearing aids, canary-yellow glasses and a smile as wide as Broadway, Hockney acknowledges the usual health issues of age, but is insistent: “I will be there. I will survive today, tomorrow and every day until I get to Paris,” and then he laughs, the catarrhy guffaw of a smoker for the last 65 years, cigarettes’ finest friend as well as the world’s biggest living art star. He has isolated himself from friends for a week fighting off a chest infection. “It is just a seven-hour car journey and then I am there,” he explains. The force of personality as well as his artistic vision undimmed; “I will never stop painting,” he says. As ever, no one or no thing will stop him doing exactly what he wants. As the Parisians might say, plus ca change: he is in no doubt he will be there, next week.

This has been a two-year project ever since Hockney (with JP, his devoted longtime French partner, by his side) called Rosenthal on FaceTime and made him an offer he could not refuse: to curate this bumper exhibition at the Louis Vuitton space in Paris. That call has also spawned an impressive book by Rosenthal on Hockney. The show is a spectacular, no expense spared, destination event for all art lovers.

“When they called I swallowed hard – I was then 78 and doing two other shows but then gave an instant yes. It has been an education and a privilege. I have learned even more than I thought [about] how he is such a profound and surprising artist,” said Rosenthal.

“He is the Picasso of our times, and when I say that people laugh at me as Picasso was the archetypal artist of the 20th century. But David Hockney is also an incredibly popular artist whose work changes how we see things. When there is a Picasso show at the Tate there are queues around the block; the same with David. Both really looked, and showed what they saw and brought joy.”

Rosenthal continues: “He just sees what is in front of him and he paints. Constable immortalised Dedham, Gainsborough immortalised parts of Suffolk, Turner the whole of the English countryside. David did Yorkshire, LA and California. As Beatrice said in Much Ado About Nothing, ‘I can see a church by daylight.’ It’s such a beautiful Shakespearean line and what it means is he properly sees the world in front of him. So often artists want to solve the problems of today rather than just see the world. David doesn’t want to solve problems. He just shows what is in front of him.”

According to Rosenthal, Hockney changes what we see. He creates a language. He reinvented California with pools and palm trees and boys and he has done it with Yorkshire too with hedges and spring blossom and vistas. He remembers Hockney’s anxiety in Los Angeles when he was about to go back to paint landscapes in Yorkshire. “I loved that he worried about precisely when in Spring the blossom of the hawthorn would appear in Yorkshire, and that was all he cared about. It was his Monet moment of embracing nature and art and a language which then spoke to the world.”

For four hours Rosenthal and Hockney reminisce in Rosenthal’s London home, discussing the final details of the show. Rosenthal is the most celebrated curator of the age. His 1981 “Sensation” show heralded the Young British Artists with showmanship and intellect, and woke the art world up to a sense of shock as well as the new. Millions of people have seen Rosenthal-curated shows which are as popular as they are serious – and Hockney very much wanted to get Rosenthal to oversee the show in Paris. It has been totally absorbing for them both.

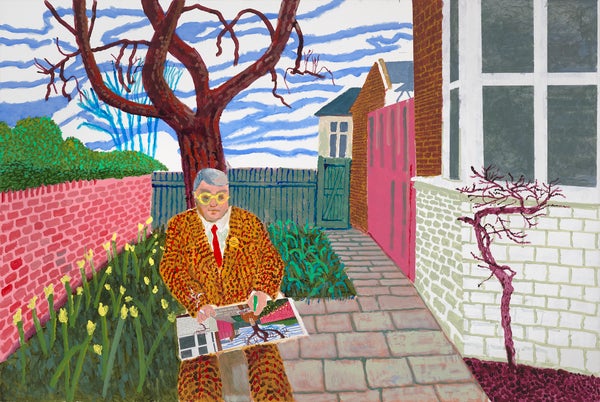

The shows mostly spans the last 25 years. Among its 70 works is a painting of Lewis, Hockney’s nurse who, of course, like everyone and everything in his life became a subject. He stares out in his blue nurse’s uniform with a Hockney badge pinned on his chest saying “End Bossiness Soon”. It’s classic Hockney: a reminder that he hates any interference. Smoking, drinking, sex, clothes, convention are all too bossily controlled, as far as he is concerned. Another picture is called “David Hockney in the garden so up yours, up yours, up yours”. More laughter from its creator. The joy of life and creating and talking are palpable.

The two men go back a long way, and their chat is light and learned, from the different aspects of what art is and can be, to who and what they’ve liked in their 60 years of friendship. They first met at the Hard Rock Cafe in 1963 and both recall it vividly. Rosenthal remembers: “I was with a friend of mine called Karl Bowen, a painter and Kellogg’s heir who was a friend of David and we then all had dinner. David always had a very memorable face with that peroxide hair and, as we know, blondes have all the fun!”

Their lives intermittently interwove. The younger man remains in complete admiration to this day.

“He’s 87. He has smoked, I don’t know, maybe 100 cigarettes a day and he still smokes,” continues Rosenthal. “His lungs are not in a good way and he accepts that fact. For him smoking is a symbol of freedom, to end bossiness. He doesn’t like being told on the packet some awful scare warning. He is very conscious of his physical fragility but his mind is as clear as is his memory.”

As with Moses and mountains, Hockney’s world has not got smaller. He summons the world to him and sends out his view from his chair, armed always with brush and paint. The concert pianist Yuja Wang came by and played in his studio. Others are constantly on the phone. But the painting has never stopped. As well as Lewis he has a female nurse, Sonia, also immortalised in paint by their most famous patient. He also whizzes around the park in his wheelchair, blue spectacles and a blue-threaded tweed matching the blue Spring skies of London.

“He paints what is in front of him; it’s the world of his imagination taking what is in front of him,” explains Rosenthal. The 25 years of landscapes and digital and oil and pencil and photographs: the full kaleidoscopic range of Hockney. Rosenthal is the perfect interpreter for him. They are both professorial and disruptive, showmen and homme sérieux, who see laughter and light as good correctives to mortality and matters melancholic.

Rosenthal’s home is an 18th-century house in Soho. It is more museum or perhaps even mausoleum than traditional home, full of ancient sculptures, ballet shoes and myriad objet d’art. There is even a David Salle painting hanging in the shower. Many pictures were given by the artists he curated. In short, there is a lack of order and discipline at his home which is in total contrast to his art shows.

He is a product of escape from the Holocaust, as his parents only survived by coming to the UK from Slovakia and Germany. His grandfather was born in the 1850s. His father’s boss in the Second World War in the Free Czech army was Captain Robert Maxwell, the polymath and war soldier whose reputation twisted into crookedness.

“Art is just like a bottomless pit of pleasure,” Rosenthal volunteers. (Hockney does not disagree.) “It is the point of making life better by looking and making sense of it. I always think life is beautiful which is why I have always been against those who seem to stem or stop pleasure. Why should we let the miserable people win when there is so much beauty and joy to see – in everything?”

David Hockney 25 is on at Foundation Louis Vuitton from 9 April to 31 August