Several fans of famed Japanese animation studio behind Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle, Studio Ghibli, were delighted this week when a new version of ChatGPT let them transform popular internet memes or personal photos into the distinct style of Ghibli founder Hayao Miyazaki.

However, the trend also highlighted ethical concerns about artificial intelligence tools trained on copyrighted creative works and what that means for the future livelihoods of human artists, as well as ethical questions on the value of human creativity in a time increasingly shaped by algorithms.

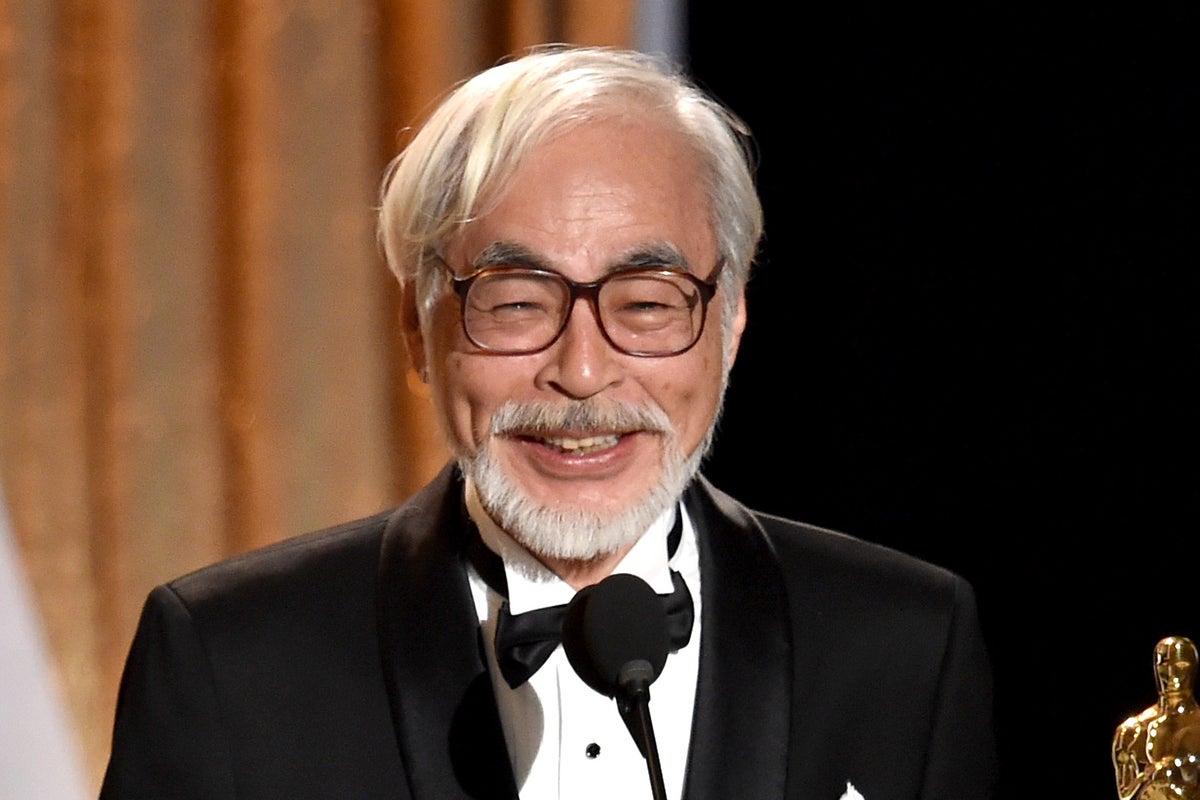

Miyazaki, 84, known for his hand-drawn approach and whimsical storytelling, has expressed skepticism about AI’s role in animation in the past.

Janu Lingeswaran wasn’t thinking much about that when he uploaded a photo of his 3-year-old ragdoll cat, Mali, into ChatGPT’s new image generator tool on Wednesday. He then asked ChatGPT to convert it to the Ghibli style, instantly making an anime image that looked like Mali but also one of the painstakingly drawn feline characters that populate Miyazaki movies such as My Neighbor Totoro or Kiki’s Delivery Service.

“I really fell in love with the result,” said Lingeswaran, an entrepreneur who lives near Aachen, Germany. “We’re thinking of printing it out and hanging it on the wall.”

Similar results gave the Ghibli style to iconic images, such as the casual look of Turkish pistol shooter Yusuf Dikec in a T-shirt and one hand in his pocket on his way to winning a silver medal at the 2024 Olympics. Or the famed “Disaster Girl” meme of a 4-year-old turning to the camera with a slight smile as a house fire rages in the background.

ChatGPT maker OpenAI, which is fighting copyright lawsuits over its flagship chatbot, has largely encouraged the “Ghiblification” experiments and its CEO Sam Altman changed his profile on social media platform X into a Ghibli-style portrait. In a technical paper posted Tuesday, the company had said the new tool would be taking a “conservative approach” in the way it mimics the aesthetics of individual artists.

“We added a refusal which triggers when a user attempts to generate an image in the style of a living artist,” it said. But the company added in a statement that it “permits broader studio styles — which people have used to generate and share some truly delightful and inspired original fan creations.”

Studio Ghibli hasn’t yet commented on the trend. The Japanese studio and its North American distributor didn’t immediately respond to emails seeking comment on Thursday.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

As users posted their Ghibli-style images on social media, others began to share Miyazaki’s previous comments on AI animation, as well as their thoughts on why they believe the AI images go against the ethos of the famed auteur.

In a 2016 meeting, when shown an AI animation demo, Miyazaki famously responded: “I am utterly disgusted. If you really want to make creepy stuff you can go ahead and do it. I would never wish to incorporate this technology into my work at all.”

The team member demonstrating the animation explained that AI could “present us grotesque movements that we humans can’t imagine,” adding that it could be used to depict zombie movements.

That prompted Miyazaki to tell a story.

“Every morning, not in recent days, I see my friend who has a disability,” Miyazaki said. “It’s so hard for him just to do a high five; his arm with stiff muscle can’t reach out to my hand. Now, thinking of him, I can’t watch this stuff and find it interesting. Whoever creates this stuff has no idea what pain is.”

“I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.

“Irony is dead and all but it’s pretty depressing to see Ghibli AI slop on the timeline not only because Miyazaki famously thinks AI art is disgusting but because he’s spent the last 50 years making art about environmental waste for petty human uses,” posted a fan on X, formerly Twitter.

A 2024 study found that AI systems were leading to vast emissions, which in turn are increasing as more energy is required to run the evolving systems. OpenAI’s current GPT-4, for instance, uses 12 times more energy than its predecessor, the study said.

The energy used in training the systems is only a small part of work, and requires an estimated 960 times more energy than a training run when the AI tools are actually being used.

In particular, many are upset with the official US government X account using the trend to generate an image of an immigrant being arrested and deported.

“To see something so brilliant, as wonderful as Miyazaki’s work be butchered to generate something so foul. God I hope Studio Ghibli sues the hell out of Open Ai for this,” posted one user.

In October 2024, an AI-generated trailer for a live-action version of the 1997 film Princess Mononoke led to massive backlash after going viral on social media.

The AI trailer used the English voice acting from the original film, which featured talents like Billy Cudrup, Clare Danes and Minnie Driver, and completely reimagined the hand drawn animation of the Japanese movie as if real people were playing the parts, albeit with CGI.

“I genuinely dunno if we’ll get a better example of why AI art is garbage than someone taking one of the most purposefully made, beautifully animated films in history and reducing it to a bunch of boring looking shots that are barely connected but somehow all look the same,” a fan wrote on X.

OpenAI didn’t respond to a question on Thursday about whether it had a license.

Josh Weigensberg, a partner at the law firm Pryor Cashman, said that one question the Ghibli-style AI art raises is whether the AI model was trained on Miyazaki or Studio Ghibli’s work. That in turn “raises the question of, ‘Well, do they have a license or permission to do that training or not?’” he said.

Weigensberg added that if a work was licensed for training, it might make sense for a company to permit this type of use. But if this type of use is happening without consent and compensation, he said, it could be “problematic.”

Weigensberg added that there is a general principle “at the 30,000-foot view” that “style” is not copyrightable. But sometimes, he said, what people are actually thinking of when they say “style” could be “more specific, discernible, discrete elements of a work of art,” he said.

“A Howl’s Moving Castle or Spirited Away, you could freeze a frame in any of those films and point to specific things, and then look at the output of generative AI and see identical elements or substantially similar elements in that output,” he said. “Just stopping at, ‘Oh, well, style isn’t protectable under copyright law.’ That’s not necessarily the end of the inquiry.”

Artist Karla Ortiz, who grew up watching Miyazaki’s movies and is suing other AI image generators for copyright infringement in a case that’s still pending, called it “another clear example of how companies like OpenAI just do not care about the work of artists and the livelihoods of artists.”

“That’s using Ghibli’s branding, their name, their work, their reputation, to promote (OpenAI) products,” Ortiz said. “It’s an insult. It’s exploitation.”