NASA scientists said Wednesday that they’ve unearthed new secrets about the moon.

Specifically, they’ve gotten a better look at the celestial body’s interior by analyzing gravity data collected from an orbiting spacecraft.

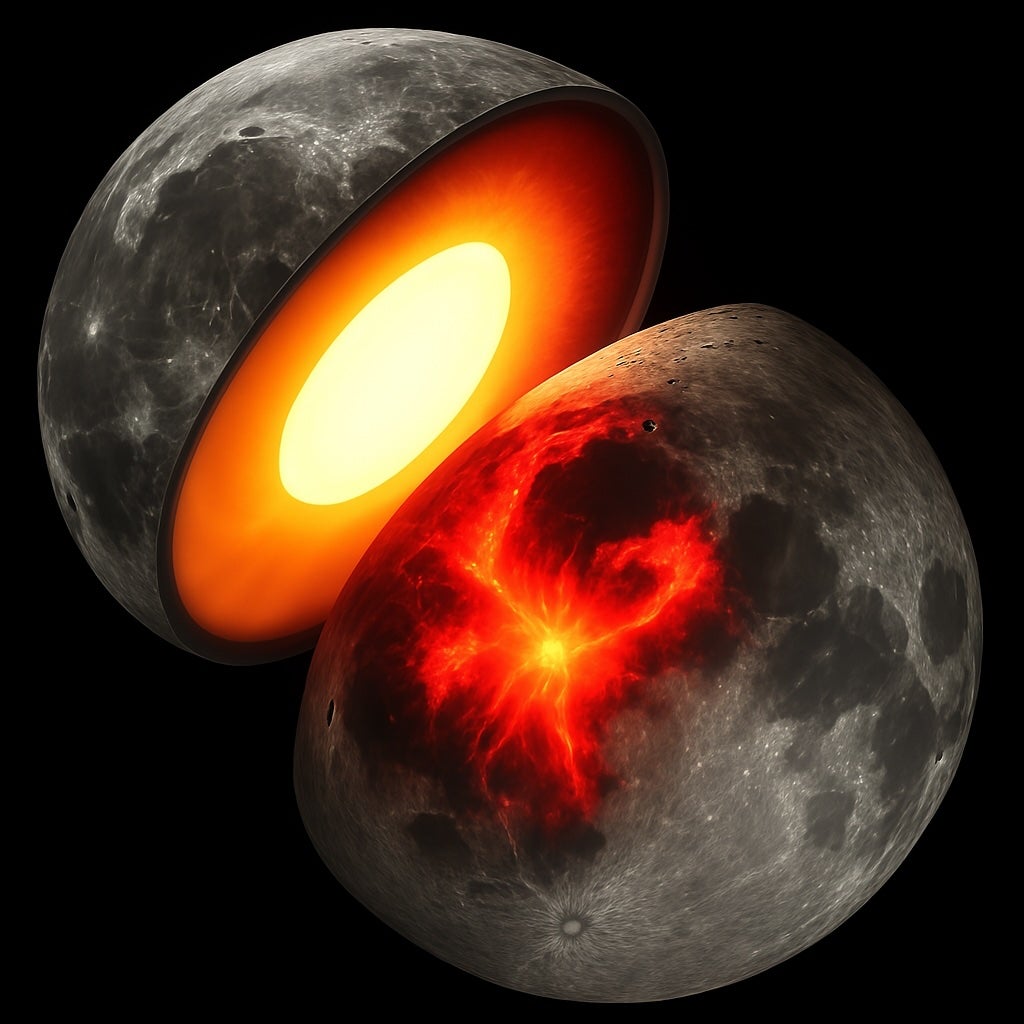

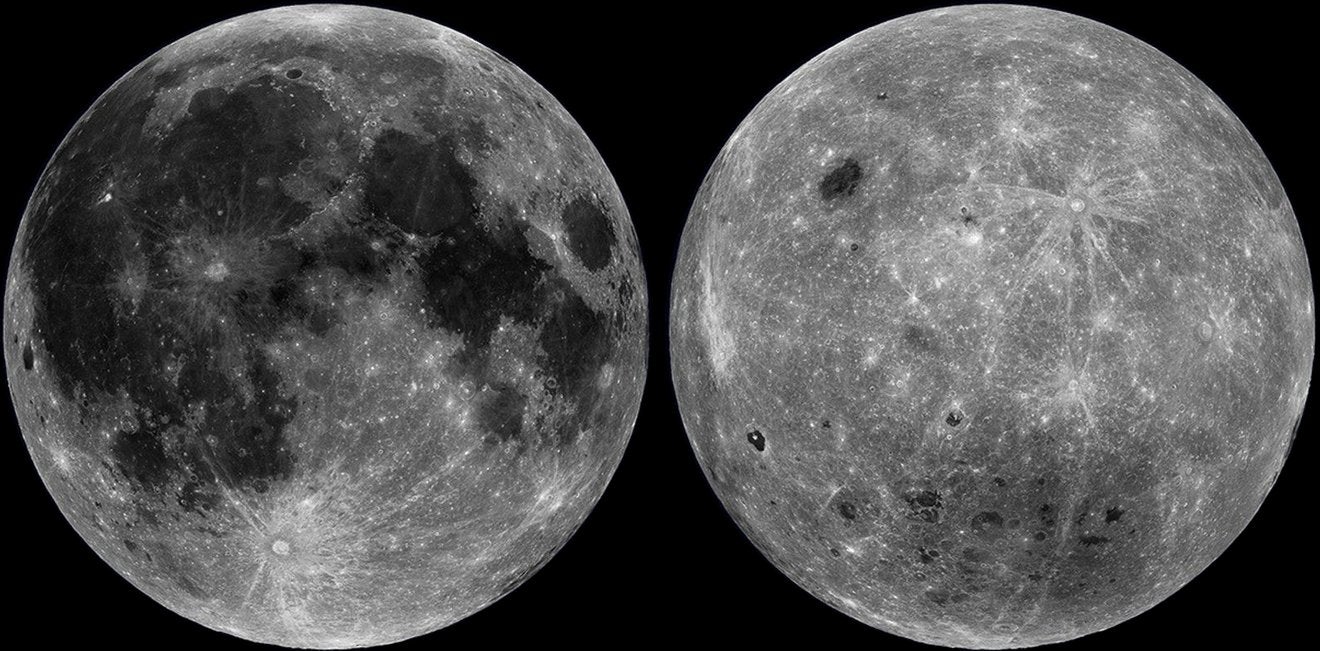

What that analysis has found is a stark difference between the internal structures of the moon’s near and far sides. The near side has vast plains formed by molten rock, but the far side is more rugged. The moon once began as a molten world, and much of its ancient surface is covered with lava.

Some theories suggest volcanism two to three billion years ago resulted in differences to the planet’s interior that would have caused radioactive elements to accumulate deep inside the near side’s mantle. This study offers the strongest evidence for that theory yet.

“We found that the moon’s near side is flexing more than the far side, meaning there’s something fundamentally different about the internal structure of the moon’s near side compared to its far side,” Ryan Park, supervisor of the Solar System Dynamics Group at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, explained in a statement. “When we first analyzed the data, we were so surprised by the result we didn’t believe it. So we ran the calculations many times to verify the findings. In all, this is a decade of work.”

The findings were published in the journal Nature.

To reach these conclusions, they developed a new gravity model of the moon, which helps look at variations in gravity as it orbits our blue marble.

The variations cause the moon to flex due to Earth’s tidal force. Just as the moon can dictate tides on Earth, the Earth exerts a gravitational pull on the moon.

They used data on the motion of the GRAIL mission’s Ebb and Flow spacecraft; it orbited the moon in 2011 and 2012.

With the help of a supercomputer, the study’s authors produced what they say is the most detailed gravitational map of the moon to date. A gravitational map, showing gravity measurements across the moon.

Looking at their results and comparing them with other models, Park’s team found a small but greater-than-expected difference in how much the hemispheres deform.

In a separate study, they used the same technique to peer into the interior of Vesta, an object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. They found that Vesta likely has a small or no core, unlike previous theories. They recently applied a similar technique to Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io, revealing that the fiery moon is unlikely to possess a global magma ocean.

“Gravity is a unique and fundamental property of a planetary body that can be used to explore its deep interior,” Park said. “Our technique doesn’t need data from the surface; we just need to track the motion of the spacecraft very precisely to get a global view of what’s inside.”