Ellie Rowsell, the mercurial, leather-clad frontwoman of Britain’s foremost guitar band Wolf Alice, is curled up on the edge of a record label’s sofa and pondering why she writes the things she does. “When a song is born of personal experience, you think you’re protected by the fact that you’re making art or whatever,” she says, through rubs of her eyes. “But you’re not. I’ve had people ask us, ‘Oh, is this song about her boyfriend?’. And it’s really frightening and scary. I had a big freakout about it. I’m a private person – why am I airing my dirty laundry? And because it’s a song, you have to make it a bit over the top and exaggerate what’s happened to you, but then that makes you feel like you’re being a drama queen. Even if I think I’m protecting myself by calling it art.”

It may be inescapable. There’s a naked emotionality to many of Wolf Alice’s best-known songs, from the sneaky rage of 2021’s florid “Safe from Heartbreak (if you never fall in love)” (“I ain’t a plaything/ To make life exciting/ You f***ed with my feelings”), to the brutal honesty of 2017’s “Don’t Delete the Kisses”, with its airy chants of “What if it’s not meant for me? Love”. But the point, she says – slanted, stretching and suddenly self-admonishing in an oh-god-I’m-not-making-any-sense sort of way – is that she’s come to understand that it’s not too much of a big deal. “Songs are true and not true, do you know what I mean?” She coughs.

The discussion is gendered, too, adds the band’s bassist Theo Ellis, dressed in a denim jacket, his hair peroxide blonde. “For a guy, it’s like a ‘forlorn love song’ rather than ‘a breakup song’,” he says. “It’s always semi-positive vocabulary that’s attributed to it.”

“A culture of autofiction is quite prevalent at the moment, though, isn’t it?” adds guitarist Joff Oddie, on the trend of authors and pop stars – among them Rachel Cusk and Taylor Swift – blurring autobiography and fiction in their work. “F***ing mountains of autofiction. It’s interesting.” Everyone nods.

We’ve been together for about five minutes (drummer Joel Amey is stuck on a train and can’t make it to our interview), and already the interpersonal rhythms of Wolf Alice are clear. On record, Rowsell is an absolute beast of a vocalist, the softest of falsettos transforming within seconds into screams and roars. Her lyrics are sledgehammers, elegantly vulnerable sum-ups of heartache, confusion and millennial woe, sung across sounds that hopscotch between folk, shoegaze, dream-pop and rock. They’re the reason Wolf Alice are as big as they are: a self-made UK success story in an increasingly fraught record industry, with three albums to their name, each of them at least nominated for the Mercury prize (2017’s Visions of a Life took the win). A fourth album – next month’s The Clearing – is on the way.

What a difference a venue makes. In one corner of this label office, Rowsell hugs her knees, circles conversational topics, thinks and then re-thinks ideas out loud, apologises. Opposite her is Ellis, who absorbs Rowsell’s ideas and smoothes them out, as if to put a button on them. Oddie, sat in the middle, interjects with pragmatic, professorly asides. Wolf Alice are far more rambling and blessedly normal than the intimidatingly cool rock stars they become on stage. They’re happy to cop to it.

“I used to think that putting in effort wasn’t cool,” Rowsell explains. “But now I’m older, I’m like… it’s pretty cool to try. It’s brave to try, and being brave is cool, really.”

“What’s amazing is thinking about what cool actually is as a philosophical concept,” Oddie adds. “Do you know what I mean?”

The Clearing feels like the band’s most mature record, if only because the anxious and unsettled melancholy that underpinned albums one through three has been replaced by a sigh of acceptance. They’re all in their thirties now, so it sort of tracks. “I must be a narcissist,” Rowsell sings on the oops-did-I-just-say-that opener “Thorns”. “God knows I can’t resist making a song and dance about it.” By album’s end, though, Rowsell has shrugged off her nerves. “I can be happy, I can be sad, I can be a bitch when I am mad,” she boasts on “The Sofa”. “Be no one thing – the intellectual beauty queen and the wild thing.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

When I catch up later with Amey, finally free of the evils of Britain’s train lines, he recalls the band taking a more considered approach to the record’s soundscape than ever before. “When you look back at our previous albums, they’re different snapshots of how you think about records,” he says. “Our first one was a collection of things we’d all been writing forever. We were free to experiment on our second one – and went in so many different directions out of pure excitement. And with [2021’s] Blue Weekend, it was like we were collecting all the things we thought sounded the best.”

The Clearing, then, is a more streamlined affair, the majority of its tracks coated in a whimsical, maximalist flair that brings to mind Seventies prog-rock and pop, and acts such as ELO, Fleetwood Mac and T-Rex. “White Horses” is a dazzlingly cinematic bit of soul-baring with Amey, on rare lead vocals, unpacking his family history. “Passenger Seat” is full of crunchy guitars and dramatic pauses. The gorgeous “Bread Butter Tea Sugar” collides pretty strings and big, stomping synths.

The album also marks the band’s first release on a major label, Columbia, after they left the UK-based Dirty Hit in 2024. The timing of their departure raised eyebrows – the news broke shortly after The 1975’s Matty Healy stepped down as the label’s creative director following a series of controversies – but Ellis says this was a total coincidence. “We finished our contract and we wanted to just do something different,” he says. “We don’t do many things the same twice.”

Signing with Columbia and jumping into an impending arena tour (a first for them) suggests a band eager to become bigger than ever. But this is a narrative that’s been weirdly stuck in place since the band’s early days. It partly comes with the territory: with a handful of EPs to their name and three years of touring tiny venues in and around north London, Wolf Alice arrived in 2015 atop a wave of hype, the UK music press insisting they were the saviours of a genre on life support. It was their raw talent that rescued them from the dangerous burden of expectations, but ideas of ever grander ambition have trailed them since.

“We’ve always been, like, reaching for the stars,” Ellis laughs, with a roll of his eyes. And, he adds, “we haven’t had to compromise who we are.”

The same ethos applies to their politics, too. We’re chatting a few weeks after the band played a barnstorming, sundown Other Stage set on the last night of Glastonbury. The band are aware that this year’s festival was largely dominated in the public sphere by conversation around performances by pro-Palestine hip-hop artists Kneecap and Bob Vylan. But it didn’t feel so fraught – or even galvanised – on the ground. “The disparity between the way it was presented in the media, and actually being at the festival is hugely different to me,” Ellis says. “It didn’t feel like some kind of sinister protest event.”

During Wolf Alice’s performance, Rowsell said: “We want to express our solidarity with the people of Palestine, and we shouldn’t be afraid to do that.” It was one of a number of political messages made by performers at the festival – if not during The 1975’s Pyramid Stage set on the Friday night, in which Healy expressed his eagerness to not make political statements.

“What did he say?” Oddie asks.

“‘I don’t want to be remembered for politics’ or something like that,” Rowsell replies. “‘We should be talking about friendship and happiness.’”

All three laugh.

“Cool, bro,” Ellis snorts. “In regards to how much we talk about this stuff, we use our platform and we like to try and use it as effectively as we can for things that the four of us are united behind.”

“You need to be selective, though,” Oddie says. “Because people turn off.”

“What do you mean?” Rowsell asks.

“I think if you are constantly talking and using your platform – which is fine for some people – it has more impact if you are selective about what you say when you enter that kind of political arena,” he explains.

“I guess,” Rowsell says. “But there’s also an urgency [right now].”

Oddie sits up to clarify what he means.

“It’s very difficult. It’s a very messy world, because all the Kneecap stuff… we’re talking about lots of very contentious areas of political discourse, about free speech. There’s gonna be pushback regardless. It’s amazing that people are talking, because this needs to be talked about. What’s going on at the moment is just horrific. The only tiny problem I have is that we sometimes lose sight of the actual issue, which is all the f***ing horrific things that are going on in Palestine. My fear is that we start talking about the culture war stuff more than we start talking about children dying.”

“But that’s the media’s fault, not the artists’ fault,” Rowsell says. She mentions seeing a video by the musician Lava La Rue, in which she stated that numerous performers expressed solidarity with Palestine at Glastonbury. “But you would think it was just Kneecap and Bob Vylan, because maybe the media is scared to show just how many people are passionate about expressing solidarity and want the government to do more or whatever. They just focus on the two things that feel controversial.”

“It’s a distraction technique,” Ellis adds. “What is happening in Palestine is underrepresented in the media, and that’s why the artists talking about it are resonating so much.”

They have no intention to stop. “The more people talk about it, the more everyone feels less scared to talk about it as well,” Rowsell says. “I do believe there is a knock-on effect.” (Since Glastonbury, Billie Eilish and this year’s Sunday headliner Olivia Rodrigo are among the artists who’ve used their social media pages to express horror at the ongoing events in Gaza. This week, Massive Attack and Brian Eno were among the artists to announce the formation of a syndicate designed to protect musicians from being “threatened into silence or career cancellation” by pro-Israeli organisations.)

If this light back-and-forth about outspokenness is an example of tension between Wolf Alice’s members, it’s entirely brief and lukewarm. They admit to having always had an unusual lack of friction, both personally and professionally. “I remember a sound man we worked with saying that he’d never worked with a band who’d finished touring an album and finished the recording of another album and were all still friends,” Oddie says.

“Just statistically, not that many bands have the same members for as long as we’ve been together,” Ellis says. “And I’m very protective of that.”

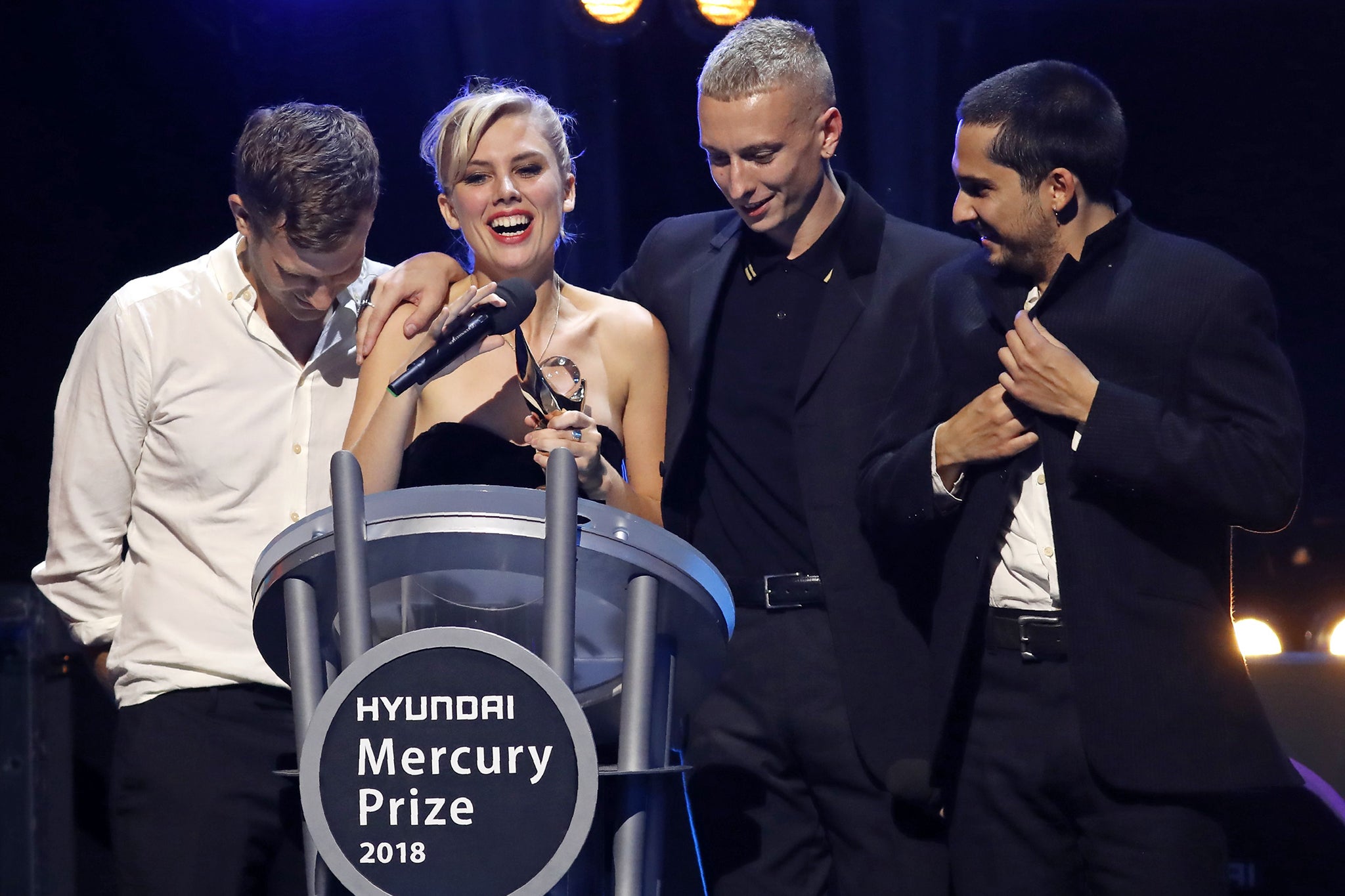

Rowsell credits their continued friendship to their refusal to become jaded. They still find excitement in every bit of rehearsal time they get, every video they film, and every photoshoot they take part in. I’m curious if they’re still fans of a big celebratory sesh – as in the lock-in they held at Camden’s riotous Hawley Arms pub right after they won the Mercury Prize in 2018.

“Have we mellowed? God, yes,” Rowsell laughs. “We don’t go out all the time and get f***ed or whatever, but I personally still need to celebrate wins. I still need to acknowledge when something feels good and feels special – it’s still so amazing what we’ve ended up doing.”

“If we win a prize, then we’ll get f***ed,” Ellis adds. “We just need to win more prizes – it’s not hard to be rowdy once every three years.”

‘The Sofa’ is out now, with ‘The Clearing’ releasing on 22 August