The difference in tumour stage at diagnosis might explain why childhood cancer survival rates differ across Europe, and in some instances, are lower in the UK, according to new research.

A new study from University College London found that survival at three years for some cancers is strongly linked to the stage of tumour at diagnosis.

Charities have said the research further reinforces that an earlier diagnosis is essential to improving survival rates for children suffering from cancer.

Angela Polanco, whose daughter Bethany was diagnosed with Wilms tumour, said: “This study provides clear evidence that we need to do more to ensure children affected by cancer have access to timely and accurate diagnosis, appropriate first-line treatment, and specialist care, wherever they live.

“Collecting and analysing this information at a population level is a crucial step towards reducing inequalities and improving survival for children with cancer.”

Researchers looked at the data of nearly 10,000 children diagnosed with six different types of cancer from 23 countries across Europe, as well as Australia, Brazil, Canada, and Japan.

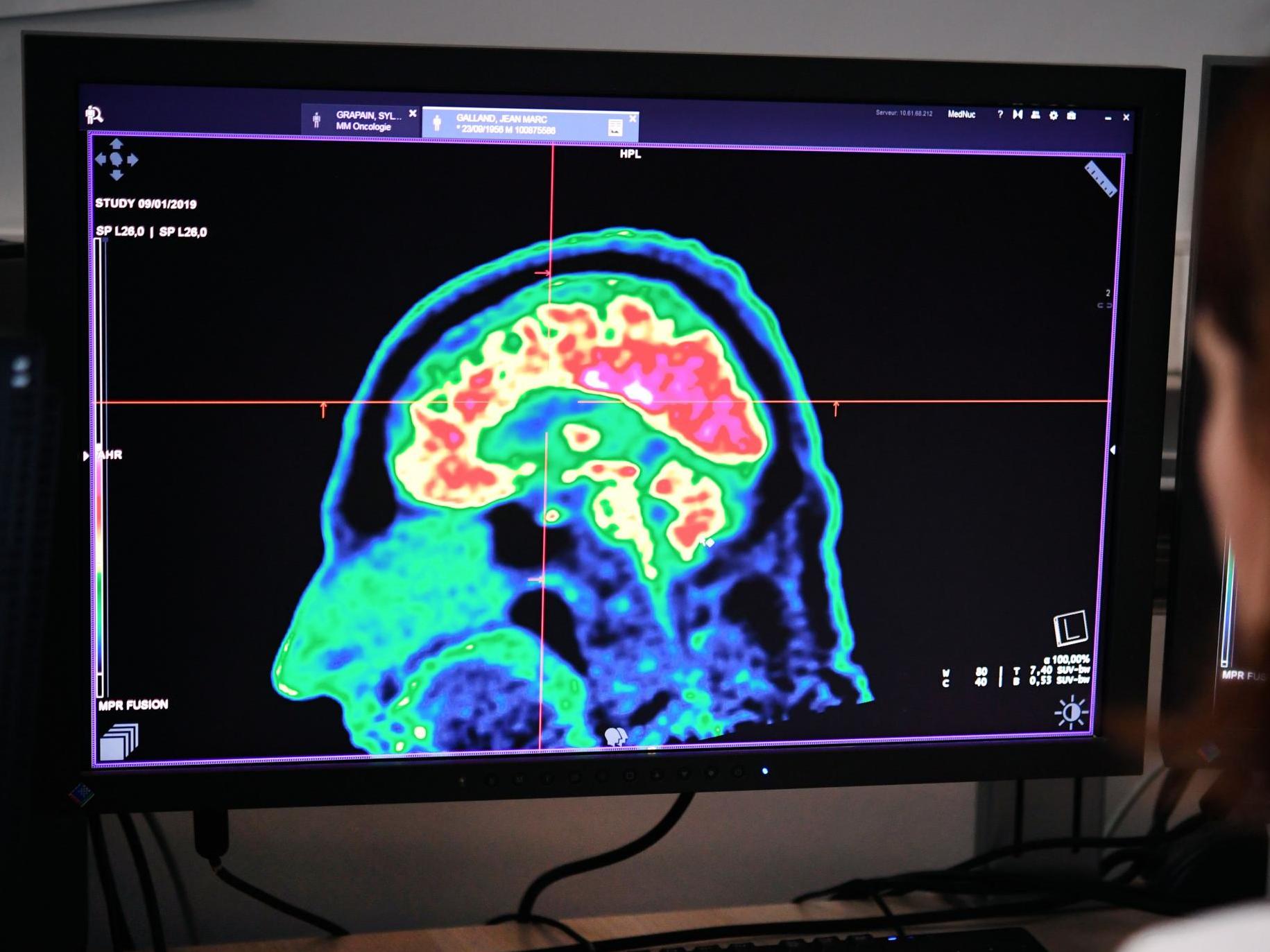

The cancers the study researched were neuroblastoma, Wilms tumour, medulloblastoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma.

In all instances, survival rates at three years were associated with the stage of tumour when diagnosed.

For Neuroblastoma, a rare cancer that affects children, researchers found kids had lower survival rates in the UK and Ireland compared with Central European countries.

They said this could be explained by the relatively later stage at which Neuroblastoma is diagnosed in the UK and in Ireland.

According to the Solving Kids’ Cancer charity, around 100 children are diagnosed with Neuroblastoma each year, making up around 6 per cent of diagnoses.

About 90 per cent of all cases occur in children younger than five, and around half of all diagnoses are to be considered high-risk.

Professor Kathy Pritchard-Jones, one of the study’s authors, said: “We have, for the first time, provided unbiased, population-level evidence for later diagnosis of some childhood cancers in the UK and Ireland.

“By analysing population-level data from cancer registries across many countries, we have been able to better understand why childhood cancer survival still differs internationally.

“Our findings show that diagnosing cancer earlier and accurately assessing how far it has spread can make a meaningful difference to survival for many children. At the same time, the study highlights that early diagnosis alone will not address all disparities, and further work is needed to understand and tackle other contributing factors.”

Last year, University of Nottingham researchers revealed that children and young people were having to wait longer than necessary for a diagnosis. The study found that teenagers and children with bone tumours were having to wait the longest to be diagnosed.

Speaking on UCL’s research, Ashley Ball-Gamble, the chief executive of the Children & Young People’s Cancer Association, said: “This study confirms that, for some childhood cancers, diagnosis in the UK still takes longer than it should.

“Because delays can affect a child’s chance of survival, campaigning for faster recognition is more important than ever.”

The Independent has contacted NHS England for comment.