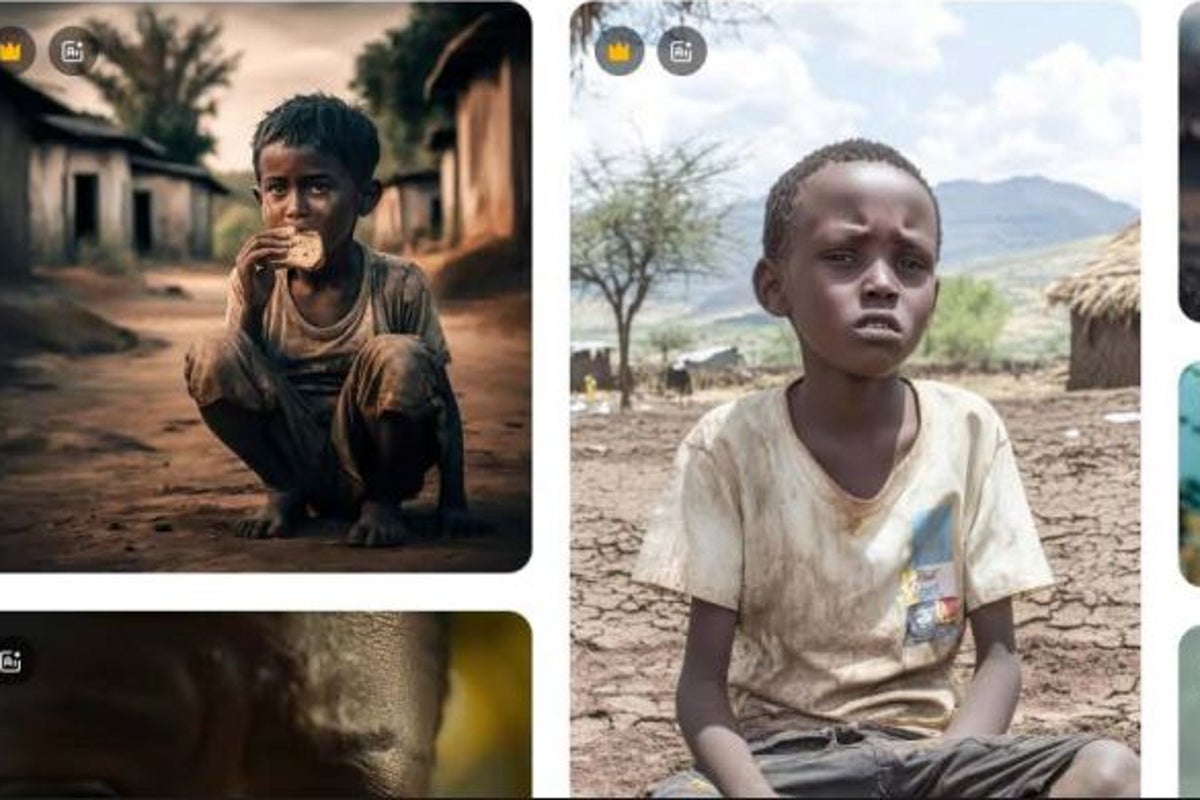

AI-generated images of starving children, refugees, victims of armed conflict, and much more, are spreading across the internet.

New research from Dr Arsenii Alenichev, at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, has uncovered a vast collection of pictures and video clips for sale. They appear to depict the struggles of poor and vulnerable people around the world but they are, in fact, the reductive fever dreams of Generative AI.

They are clearly marked as AI, so purchasers are not being deceived, but that only makes this trend all the more alarming: there is an emerging market for AI-generated poverty porn.

A quick search on stock image websites reveal pictures that are truly shocking. “Asian children” swim in rivers of waste, skeletal infants stare hungrily at the viewer, refugees scream into the void or perch in filthy encampments. And, of course, there are plenty of white Westerners coming to the rescue. Volunteers in baseball caps embracing grateful African children, picture-perfect 20-somethings pose in schools full of smiling students, and foreign doctors in white coats bring modern medicine to the needy.

Some images are just ridiculous. The caption of one reads: “Young mother cradles her child amidst the chaos of war in Africa”, which it advertises as “powerful imagery for awareness campaigns”. The backdrop to this scene of war-torn chaos is, inexplicably, a perfectly intact cafe.

We are in the foothills of AI imagery and so we must expect such obvious mistakes will be ironed out quickly. As the pictures become increasingly sophisticated and photorealistic, the difference between the real and the fake will become impossible to discern and the temptation to use them will increase. But can we ever trust AI to make images that aren’t laden with stereotypes, and is it ever ethical?

Alenichev’s earlier research exemplifies the widely-held concern in computational science: that generative AI models can be highly racialised and this is particularly visible in the images they create. The models are trained on billions of pictures from our past and

present; imbibing all of our biases and prejudices in the process.

In recent years, many NGOs have adopted ethical storytelling guidelines that forbids them from using dehumanising photographs of the people they serve. But in light of extreme funding cuts – from Keir Starmer’s slashing of the UK aid budget to the almost complete eradication of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) – many fundraising teams, in charities large and small, are under intense pressure to fill the yawning financial gaps.

Meanwhile, the need for effective visual communication has never been greater; to feed the insatiable social media accounts, websites, fundraising appeals, etc. In these circumstances the use of AI stock images for marketing might prove irresistible.

After all, fake photos of fake people are cheap. There are no photographers to contract and no trips to be arranged. There are no complex consent processes to overcome, no security risks to manage, no duty of care, no obligations. Nobody is being objectified or

exploited, right? Wrong. The peoples, places, communities, and issues being represented are being objectified and I believe their experiences are being exploited.

If you believe, as I passionately do, in the urgent need for more ethical and dignified storytelling; made with people rather than about people, then it’s clear that AI’s reductive and stereotypical representations can never be the answer.

The extent to which AI stock images are being used by charities and NGOs is unclear. What we do know is the use of AI to produce images in-house is most certainly on the rise.

There are some excellent examples of organisations using the technology to produce powerful images for campaigns, clearly signposted as the product of AI. “The Future of Nature” campaign by WWF rendered scenes of environmental collapse in a series of AI-generated paintings. Breast Cancer Now’s project “Gallery of Hope” worked with AI to create photographs of women with incurable breast cancer as they imagined their future might be, given more time.

These were carefully managed projects that required significant financial resources and expertise to achieve. The organisations involved were scrupulous in their use of AI, which happened under the watchful eye of photographers, AI specialists, campaigners and communications professionals.

The same care and attention is clearly not taken by the so-called “AI artists”, operating under ludicrous pseudonyms, as they publish images of people and places they have doubtlessly never seen with their own eyes. If they even have eyes. If they are even human.

We must hope that charities recognise the dangers, to the representation of people, to public perceptions, to trust and reputations, and refuse to use AI-generated stock images all-together. Without buyers, the marketplace for AI “poverty” porn will wither and die. As it should.

Gareth Benest is deputy executive director of the International Broadcasting Trust (IBT)

This article has been produced as part of The Independent’s Rethinking Global Aid project