Bird flu has been detected in a single sheep for the first time in England, in an area where the disease had been confirmed in captive birds.

The government said while this marked the first time avian influenza H5N1 had been found in a sheep. It is not the first time it had been detected in livestock in other countries.

Surveillance on infected premises was introduced by the government following an outbreak of the disease in dairy cows in the US.

However, the government added there was no evidence to suggest an increased risk to the country’s livestock population.

The infected sheep in Yorkshire has been culled and sent for extensive testing.

Further testing in the remaining flock of sheep was undertaken and no other infection with avian influenza virus was detected.

What is bird flu?

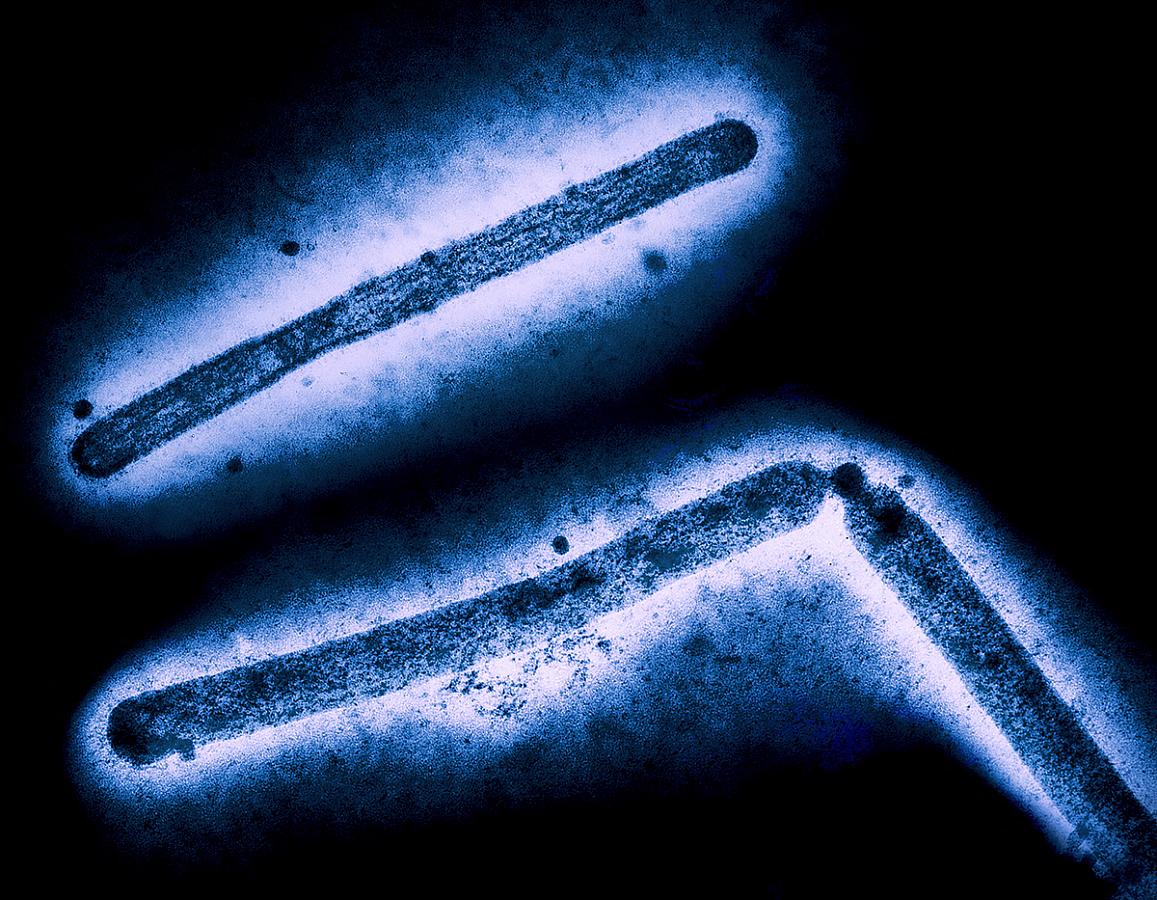

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, is the name for a number of different virus strains that infect birds.

The vast majority of strains of the virus do not infect humans. To date there have been no recorded cases of a human infected with bird flu in the UK.

In rare cases humans can catch the virus when coming into contact with live infected birds, with those working with poultry particularly at risk.

The symptoms if you do somehow catch it include a very high temperature, sickness, stomach pain, aching muscles and a cough.

It usually takes three to five days for the first symptoms to appear after becoming infected.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) the first human outbreak of the virus was found in Hong Kong in 1997.

A three-year-old boy died of respiratory failure in a Hong Kong hospital and months later the cause of death was established to be H5N1 avian influenza. The outbreak was linked to handling infected poultry.

In January, UKHSA confirmed a case of bird flu in a person in the West Midlands, after prolonged contact with a large number of infected birds on a farm. The patient was admitted to a High Consequence Infectious Disease (HCID) unit.

There is no vaccine to protect against the virus but avoiding contact with sick or dead birds and not eating undercooked poultry, or eggs can also reduce the risk of catching the virus.

Why has it been detected in sheep for the first time?

The virus does predominantly affect birds, but mammals that come into close contact with infected birds or eat infected birds can also catch it.

Globally, a huge number of kept and wild birds have been infected. However, only a small number of infections have been reported in mammals in comparison. This includes an outbreak of the disease in dairy cows in the US.

In the UK, cases have been confirmed in foxes, otters, seals and now sheep – some of these mammals are known to scavenge dead or dying birds, according to UKHSA.

Experts say it is not “unexpected” that a sheep that came into close contact with an infected bird also caught the virus.

“It is too early to consider whether such virus is capable of onward spread within sheep, but this was an isolated small holding with a small number of birds and sheep,” Professor Ian Brown, Group Leader at the Pirbright Institute said.

He added: “The pathways of spread of these viruses in the USA has been shown to be by movement of dairy cattle in commercial milking herds which appears not applicable in this single case of one animal becoming infected.

“It does emphasise the importance of separating species and maintaining good farm hygiene.”

Ed Hutchinson, Professor of Molecular and Cellular Virology, at the University of Glasgow was surprised to learn the virus was detected in the sheep’s milk.

He said: “It suggests parallels to the ongoing H5N1 outbreak in dairy cattle in the USA, where the virus is spreading through cow’s milk. At the moment there is no evidence of any ongoing transmission from the sheep, and the case appears to have been contained.

“More work will be needed to understand what’s going on here – in particular to understand if this is a very rare or one-off event which happened because there was a lot of H5N1 around and this was just the wrong sheep in the wrong place, or whether sheep infections with H5N1 might become more common in the future.”