The US is pushing for a deal that would grant it 50 per cent of Ukraine’s revenues from critical minerals, oil, gas, and stakes in key infrastructure, such as ports, through a joint investment fund.

Despite Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky rejecting an earlier version, negotiations have intensified, with Ukraine’s parliament speaker, Ruslan Stefanchuk, saying that Kyiv aimed to conclude the deal by 24 February, marking the third anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Olha Stefanishyna, who is responsible for Ukraine’s European and transatlantic relationships, also posted on X: “Ukrainian and US teams are in the final stages of negotiations regarding the minerals agreement.

“The negotiations have been very constructive, with nearly all key details finalised,” she said in a post that was taken down on social media for several hours before being reinstated.

The details of the draft offer reportedly guarantee Ukrainian sovereignty which had been an issue with earlier Trump proposals. These had said nothing about the future security for Ukraine but demanded it raise $500bn in payback for money spent by the US in defence of the country.

On Sunday, Mr Zelensky pushed back against the Trump administration’s demands for billions in Ukrainian natural resources as part of the minerals deal. “I am not signing something that 10 generations of Ukrainians will have to repay,” Mr Zelensky had said, indicating that negotiations would continue. He estimated that repaying $500bn using Ukraine’s natural resource revenues could take 250 years, calling the amount unrealistic.

“If we are forced and we cannot do without it, then we should probably go for it,” he, however, added.

Meanwhile, a UN resolution condemning Russia’s invasion passed despite US and North Korean opposition, and Mr Trump suggested the deal was close to completion.

The US president announced earlier that the war-torn country was on board with his plan. “We’re telling Ukraine they have very valuable rare earths,” Mr Trump said. “I told them that I want the equivalent of like $500bn worth of rare earths, and they’ve essentially agreed to do that.”

The Kremlin jumped on the comments, saying it demonstrated the US is no longer willing to provide free aid to Kyiv before adding that it was against Mr Trump giving any help to Ukraine whatsoever.

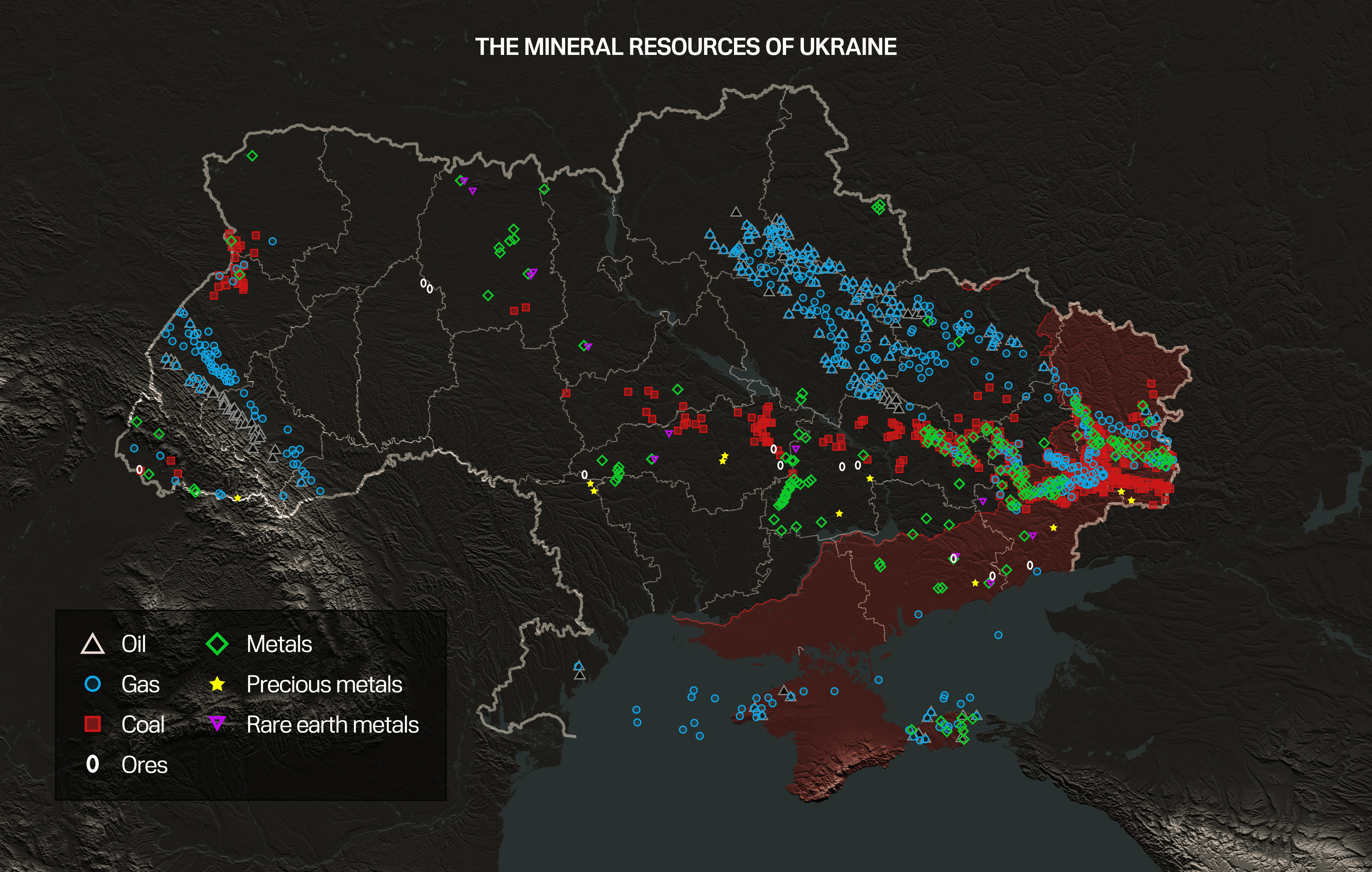

Below, we look at where these resources are in Ukraine, and why Kyiv has struggled to mine these minerals.

What are Ukraine’s rare earths?

Ukraine is sitting on one of Europe’s largest deposits of critical minerals, including lithium and titanium, much of which is untapped. According to the Institute of Geology, Ukraine possesses rare earth elements such as lanthanum and cerium, used in TVs and lighting; neodymium, used in wind turbines and EV batteries; and erbium and yttrium, whose applications range from nuclear power to lasers. The EU-funded research also indicates that Ukraine has scandium reserves but detailed data is classified.

Mr Zelensky has been trying to develop these resources, estimated to be worth more than £12 trillion, based on figures provided by Forbes Ukraine, for years.

In 2021, he offered outside investors tax breaks and investment rights to help mine these minerals. These efforts were suspended when the full-scale invasion started a year later.

Anticipating the notoriously transactional Mr Trump might take an interest in this, Mr Zelensky then placed the mining of these minerals into his victory plan, which was drawn up last year.

The minerals are vital for electric vehicles and other clean energy efforts, as well as defence production.

Estimates based on government documents suggest that Ukraine’s resources are also highly varied. Foreign Policy found that Ukraine held “commercially relevant deposits of 117 of the 120 most-used industrial minerals across more than 8,700 surveyed deposits”.

Included in that is half a million tonnes of lithium, none of which has been tapped. This makes Ukraine the largest lithium resource in Europe.

Ukraine’s reserves of graphite, a key component in electric vehicle batteries and nuclear reactors, represent 20 per cent of global resources. The deposits are in the centre and west.

It is not surprising that Mr Trump appears keen on benefiting from this, especially as China remains a key player in the mining of minerals such as titanium.

But Vladimir Putin’s invasion has not only delayed Ukraine’s plans to mine these minerals, it has also led to much of these resource-rich areas being destroyed and then occupied.

A little over £6 trillion of Ukraine’s mineral resources, which is around 53 per cent of the country’s total, are contained in the four regions Mr Putin illegally annexed in September 2022, and of which his army occupies a considerable swathe.

That includes Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson, though Kherson holds little value in terms of minerals.

The Crimean peninsula, illegally annexed and occupied by Mr Putin’s forces in 2014, also holds roughly £165bn worth of minerals.

The region of Dnipropetrovsk, which borders the largely occupied regions of Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia, and sits in the face of an advancing Russian army, contains an additional £2.8 trillion in mineral resources.

Russian difficulties with major military operations seem likely to preclude a serious attempt to take the region but mining operations in the area would be perilous with Moscow’s soldiers so close.

Other ores are well within the sites of Russia’s forces. One lithium ore on the outskirts of a settlement called Shevchenko in Donetsk is less than 10 miles from the town of Velyka Novosilka, recently captured by Mr Putin’s troops.

However, while Ukraine has a highly qualified and relatively inexpensive labour force and developed infrastructure, investors highlight a number of barriers to investment. These include inefficient and complex regulatory processes as well as difficulty accessing geological data and obtaining land plots. Such projects would take years to develop and require considerable up-front investment, they said.

What happens next?

Details of any deal will likely develop in meetings between US and Ukrainian officials. Mr Zelenskyy and Mr Trump will probably discuss the subject when they meet.

US companies have expressed interest, according to Ukrainian business officials. But striking a formal deal would likely require legislation, geological surveys and negotiation of specific terms.

It is unclear what kind of security guarantees companies would require to risk working in Ukraine, even in the event of a ceasefire. And no one knows for sure what kind of financing agreements would underpin contracts between Ukraine and US companies.

.png?trim=195,444,193,439&width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)