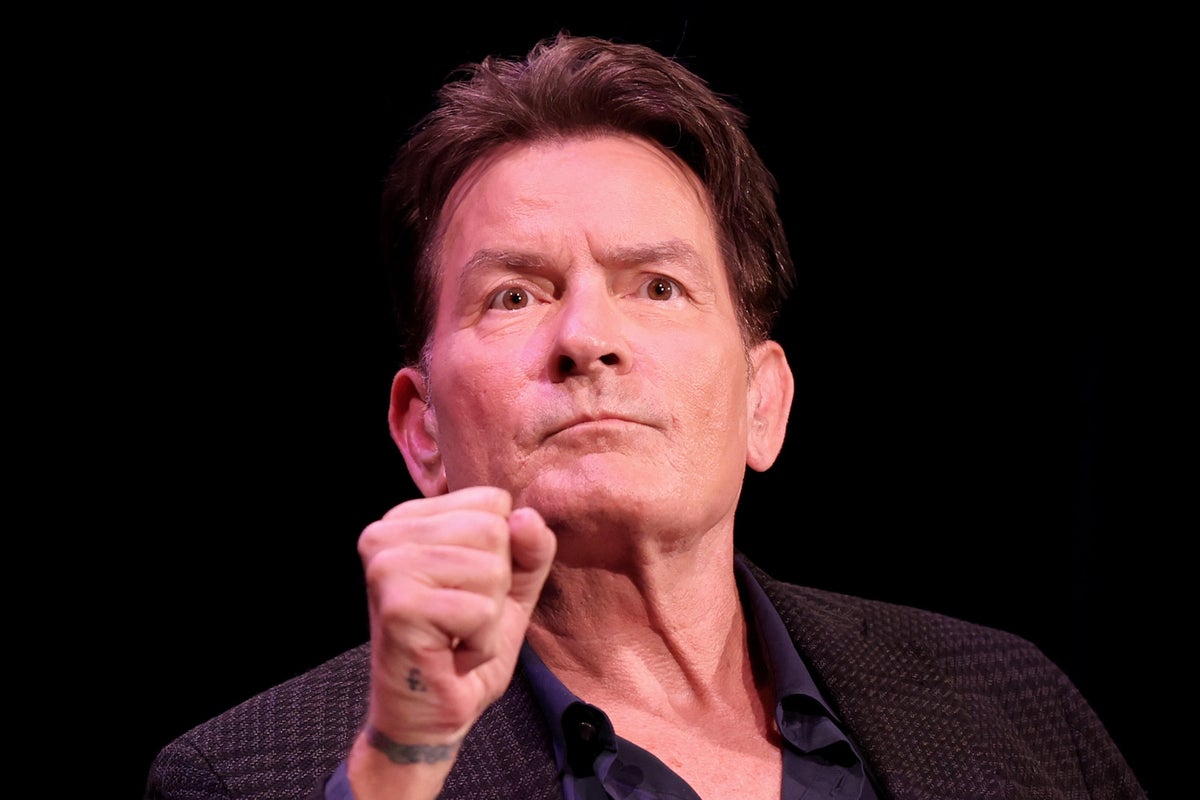

One of the unexpected turns in Charlie Sheen’s new memoir, mock-brazenly titled The Book of Sheen, comes towards the end, when we finally reach the doorstep of Two and a Half Men. The hit sitcom gave Sheen his best-known role, and made him, for a while, the highest-paid actor on television; here, though, there is no juicy behind-the-scenes reminiscing and little by way of gossipy anecdote. His eight years on the show are all but breezed over, subsumed by a granular recounting of his longstanding drug addiction. But that is, to a large extent, the story of Sheen.

There’s a metatextual component to this book, which devotes much of its first half to interesting and involved recollections about Sheen’s work on films such as Platoon and Wall Street, before his extracurricular misadventures steal focus. Sheen – now eight years sober, speaking to us as a quelled tornado – doesn’t glorify his drug use or womanising, but handles it with a sort of wry irreverence. He knows as well as anyone that it can’t be fenced into a chapter; his struggles aren’t some discrete facet of his celebrity, but the very essence of it. Ever since the months-long, highly public and reputation-ruining 2011 meltdown that saw him fired from Two and a Half Men, and led to a succession of outrageous, drug-fuelled videos, Sheen has been synonymous with his addictions; his artistry as a performer feels almost entirely forgotten.

And yet, the specifics of Sheen’s life provide a number of interesting windows onto the industry. His father Martin Sheen rose to fame as a stellar actor in films such as Badlands and Apocalypse Now, before later ageing into a dignified career-capping stint as The West Wing’s commander-in-chief. His father’s work gave Sheen early exposure to the film industry; a substantial early chunk of the book is devoted to his experience as a child around the set of Apocalypse Now in the Philippines.

Sheen’s decision to follow in his father’s footsteps seems to be born of a genuine fascination with film: as a child, he would shoot his own amateur efforts on a Super 8 camera, alongside his brother Emilio Estevez, and future-star friends such as Sean Penn and Rob Lowe. Sheen may be an early example of what’s now called a “nepo baby”. In Sheen’s telling, however, his success was largely unconnected to his father’s, and the decision to adopt his father’s stage surname motivated chiefly by a wish to distance himself from the stigma of his own teenage delinquency.

Whatever the reason, opportunities did come expediently: Sheen’s early roles, in films such as the Best Picture-winning Platoon, and John Milius’s Red Dawn, established him as a viable movie star with a big future. Like Estevez, he was often grouped alongside the set of young, ascendant stars known as the “Brat Pack”. As the book pivots increasingly to Sheen’s off-camera antics, and his worsening involvement with illicit substances, we see the gloss of his movie career fade away. About much of his own oeuvre, Sheen is downright damning: he describes five of his movies made in 1997 and 1998 as being “rancid”, dismissing the political thriller Shadow Conspiracy with the quip, “If a film could be liquid s*** you have to drink, this one comes with a funnel.”

Thrown into the mix are a collection of the sort of amusing, name-droppy anecdotes you might expect from a Hollywood memoir. There’s the time Sheen played table tennis with OJ Simpson (“Please understand that I’m still describing his ping-pong skills when I say: his right hand was f**ken lethal”). Or the time state governor Bill Clinton allegedly made a creepy remark after coming into the vicinity of Sheen’s young then-girlfriend. Or the time Sheen witnessed the ravenous eating habits of a late-in-life Marlon Brando.

Throughout the book, there’s a typographical playfulness that skirts the edge of affectation: things aren’t cool but “kool”; men aren’t dudes but “doods”. When it comes to some of his scandals, Sheen’s tone is more exculpatory than contrite; a violent altercation with a former partner is explained away as self-defence, with Sheen suggesting that the story had become “so radically spun you’d think I was a serial killer”. His adult life was thoroughgoingly messy, and The Book of Sheen often seems more concerned with stating this fact than trying to make sense of the mess. But maybe that’s for the best.

This new memoir coincides with the release of a Netflix documentary on Sheen, and the actor has embellished both with a series of candid interviews – a far cry from the sort of manic televised confabs he was delivering mid-breakdown. He has spoken about his life with HIV, having been diagnosed in 2011, and about his sexual experiences with other men while under the influence of drugs. (He addresses these dalliances briefly and somewhat euphemistically in the book itself.) What’s specifically worthwhile about The Book of Sheen, however, is the time it devotes to those less-lurid chapters of his life – to the not-insignificant film career that he for a time had, and the unknowable hypothetical one that he never did. The story of Sheen’s life is, sadly, the story of derailment. That the book itself is derailed by his demons might be frustrating – but it’s certainly fitting.