Steve, a film Max Porter adapted from his own novella Shy, asks us to consider what we expect from adaptation. On the page, we enter inside the mind of a teenage boy. It’s chaotic in there. We’re torn violently between love and self-obliteration, between the feeling of being very big to the feeling of being very small, always in flux and never safe. The boy, Shy, is at a boarding school for troubled kids in England in 1995. It’s known as their “Last Chance”. Porter’s writing is a provocation to sympathy. He’s asking us, before we cast our judgment, to at least live a little while inside this maelstrom.

For the screen, however, Porter chose to – in his words – “rewrite” rather than to adapt. Steve tells the same story from the point of view of the school’s headteacher, who in the novella is a rare, unwaveringly kind voice. It’s nice to see an author treat cinema as something more than an accessory to their own work. Ultimately, it’s a daring choice that yields limited results.

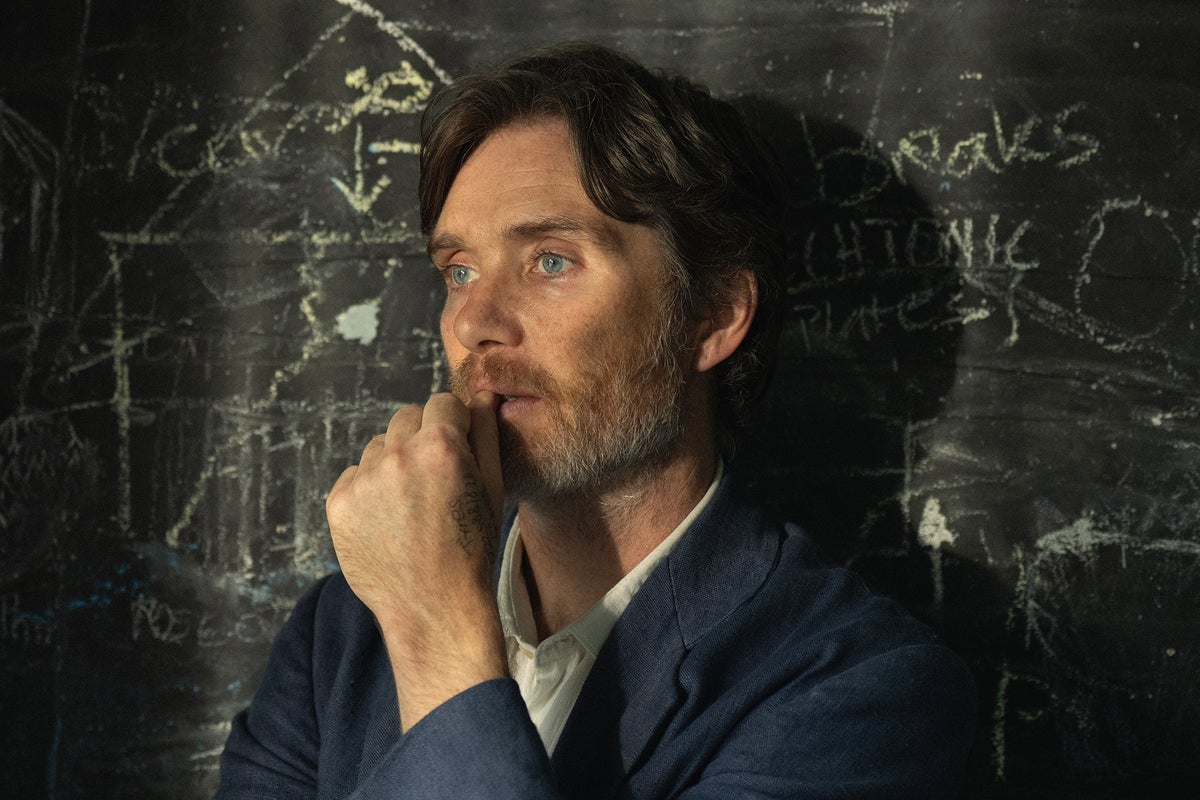

As Steve becomes the centre of our attention – and how could he not be, when he’s played by the extraordinary Cillian Murphy – Shy (Jay Lycurgo) is sidelined. He becomes the curious, tragic puzzle everyone’s trying to solve: Steve, teachers Amanda (Tracey Ullman, in a rare but effective dramatic turn) and Shola (Simbi Ajikawo, who raps under the name Little Simz), and therapist Jenny (Emily Watson). What insight we are afforded is entirely through the beautiful work of Lycurgo, who captures the very moment a mind tiptoes too closely to a painful emotion, only to stop dead in its tracks and then slide into disassociation.

Shy’s story plays out the same way, but in the background, and without the internal reasoning to make sense of it all. Steve, meanwhile, is handed a neat, condensed list of burdens plucked from the novella: he’s just been told the school has been sold and will close in six months, while a news crew barge around the place, and a conservative MP (Roger Allam) waffles on to the kids about how they should be grateful he’s saved them all from communism. Porter then hands him extra, unprocessed trauma, with added substance addiction.

This, in short, is the more conventional and palatable way to tell this story. We’re used to films about the kind and resourceful people who do such difficult work, less so about the ones who benefit from that dedication, gleefully referred to by a television presenter here as “society’s waste product”. The climactic image of two bloated, dead badgers has been swapped for a poster about “the resilient beauty of flint and limestone”.

Yet the project, spearheaded by Murphy and his producing partner Alan Moloney – who brought back their Small Things Like These director Tim Mielants – doesn’t lapse entirely into pat, sentimental mode. Murphy, for one, isn’t an actor to embellish Steve’s pain for the audience’s sake. That fundamental honesty about him is useful, too, in selling the idea of an adult who could talk straight to these kids and be trusted by them.

Mielants finds ways to capture the impressionistic, deliberately shambolic tone of Porter’s prose. At times we’re so close to Murphy’s face we can count the bristles on his chin. Then, suddenly, we’re flying around while drum and bass screams in our ear – coupled with the Nineties setting, it’s hard not to think of Danny Boyle’s bravado in these scenes. Steve is a thoughtful, impassioned film in practice. Yet it’s deliberately made itself secondary to its source material.

Dir: Tim Mielants. Starring: Cillian Murphy, Tracey Ullman, Jay Lycurgo, Simbi Ajikawol, Emily Watson. 92 minutes.

‘Steve’ is in selected cinemas from 19 September and streams on Netflix from 3 October

.jpeg?trim=81,0,81,0&width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)