Scientists have finally unravelled the complex process that generates sound during handclaps, a discovery that shows how even simple acts can be rich with physics.

The research, published in the journal Physical Review Research, shows that the characteristic “pop” sound of a clap is not just from two hands smashing into each other but a much more complex phenomenon.

The key to generating sound from clapping is a cavity of air that is compressed and pushed out of a small space.

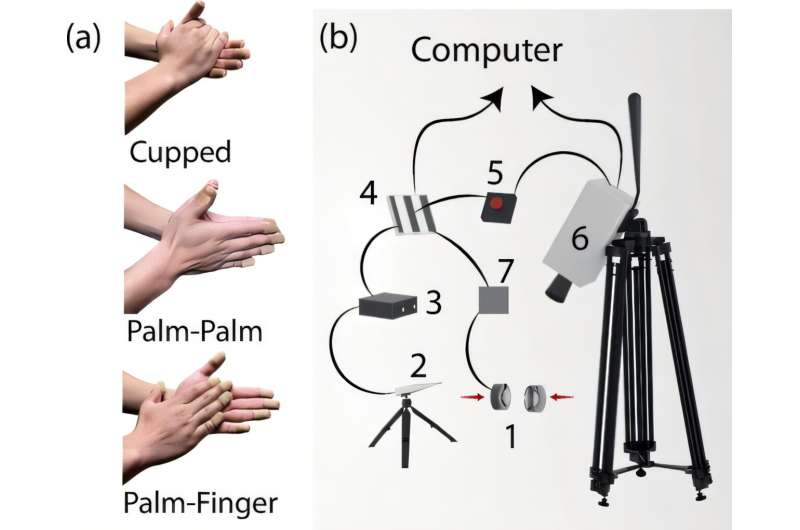

Scientists followed an interdisciplinary approach to understand clapping, using live experiments, theoretical modelling and silicone replicas of human hands.

They modified the volume and duration of claps by changing the speed, the shape of the hands and even the skin softness.

“We clap all the time but we haven’t thought deeply about it. That’s the point of the study,” said study co-author Yicong Fu from Cornell University, “to explain the world with deeper knowledge and understanding.”

“The point was not to look just at the acoustics, or the flow excitation or the collision dynamics, but to look at them all simultaneously,” Likun Zhang, another study author from the University of Mississippi, said. “That’s an interdisciplinary effort that allows us to really understand how sound relates to hand clapping.”

The study shows that when hands come together during a clap, they create a pocket of air between the palms. This pocket is rapidly expelled from the narrow opening between the forefinger and thumb, causing the air molecules to vibrate.

Scientists liken this vibration to the Helmholtz resonance principle, which is behind the tone heard when blowing across the mouth of an empty bottle.

“Traditional Helmholtz resonators have rigid walls like the glass walls of a bottle. This produces a long-lasting sound that attenuates very slowly because most of the energy contributes to the acoustic signal,” Dr Zhang explained. “But when we have elastic walls – let’s say our hands – there is going to be more vibration of the solid material, and all of that motion absorbs energy away from the sound.”

This is why clapping generates a single short “pop” as opposed to a longer noise, researchers say.

Scientists hope their research can help inform music education, where handclaps are often used for rhythm timing.

The study also shows that every person’s clap has a different sound and a different frequency, indicating that clapping can be used in the future as an identification method, like how we use fingerprints.

“One of the most promising applications of this research is human identification. Just through the sound, we could tell who made it,” Guoqin Liu, another author of the study, said.