A recent study showed that Mars was warm and wet billions of years ago. The finding contrasts with another theory that this era was mainly cold and icy. The result has implications for the idea that life could have developed on the planet at this time.

Whether Mars was once habitable is a fascinating and intensely researched topic of interest over many decades. Mars, like the Earth, is about 4.5 billion years old and its geological history is divided into different epochs of time.

The latest paper relates to Mars during a time called the Noachian epoch, which extended from about 4.1 to 3.7 billion years ago. This was during a stage in solar system history called the Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB). Evidence for truly cataclysmic meteorite impacts during the LHB are found on many bodies throughout the solar system.

Two obvious scars from this era on Mars are the enormous Hellas and Argyre impact basins; both are well over a thousand miles across and each possesses enough volume to hold all the water in the Mediterranean with room to spare.

One might not imagine such a time being conducive to the existence of fragile lifeforms, yet it is likely to be the era in which Mars was most habitable. Evidence of landforms sculpted by water from this time is plentiful and include dried-up river valleys, lake beds, ancient coastlines and river deltas.

The prevailing climatic conditions of the Noachian are still a matter of intense debate. Two alternative scenarios are typically posited: that this time was cold and icy, with occasional melting of large volumes of frozen water by meteorite impact and volcanic eruptions, or that it was warm, wet and largely ice-free.

Brightening Sun

All stars, including the Sun, brighten with age. In the early solar system, during the Noachian, the Sun was about 30% dimmer than it is today, so less heat was reaching Mars (and all the planets). To sustain a warm, wet climate at this time, the Martian atmosphere would have needed to be very substantial – much thicker than it is today – and abundant in greenhouse gases like CO2.

But when reaching high enough atmospheric pressure, CO2 tends to condense out of the air to form clouds and reduce the greenhouse effect. Given these issues, the cold, icy scenario is perhaps more believable.

One of the main science goals of the Mars 2020 Perseverance Rover, which landed spectacularly in February 2021, is to seek evidence to support either of these two scenarios, and the new paper using data from Perseverance may have done just that.

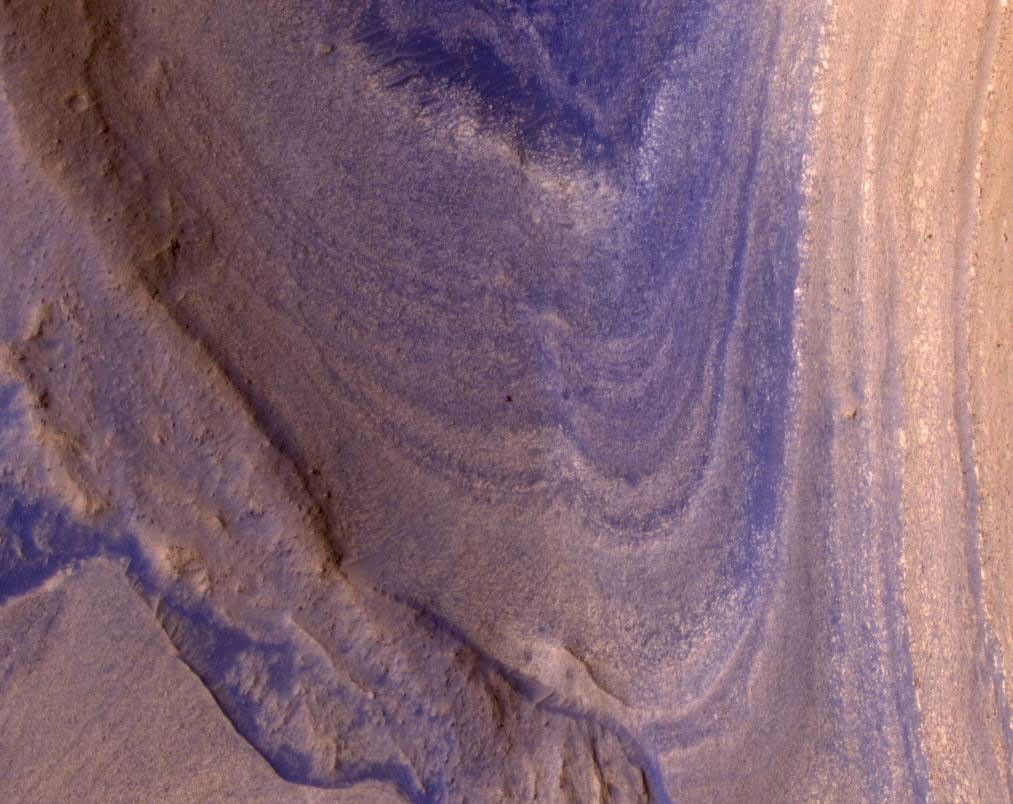

Perseverance landed at the Martian location of Jezero crater, which was selected as the landing site because it once contained a lake. Views of the crater from orbit show several distinct fan-shaped deposits emanating from channels carved through the crater walls by flowing water. Within these channels are abundant deposits of clay minerals.

The new paper details recent analysis of aluminium-rich clay pebbles, called kaolinite, located within one of the ancient flow channels. The pebbles appear to have been subjected to intense weathering and chemical alteration by water during the Noachian.

While this is perhaps not surprising for a known ancient watery environment, what is interesting is that these clays are strongly depleted in iron and magnesium, and enriched in titanium and aluminium.

This is important because it means these rocks were less likely to have been altered in a hydrothermal environment, where scalding hot water was temporarily released by melting ice caused by volcanism or a meteorite impact.

Instead, they appear to have been altered under modest temperatures and persistent heavy rainfall. The authors found distinct similarities between the chemical composition of these clay pebbles with similar clays found on Earth dating from periods in our planet’s history when the climate was much warmer and wetter.

The paper concludes that these kaolinite pebbles were altered under high rainfall conditions comparable to “past greenhouse climates on Earth” and that they “likely represent some of the wettest intervals and possibly most habitable portions of Mars’ history”.

Furthermore, the paper concludes that these conditions may have persisted over time periods ranging from thousands to millions of years. Perseverance recently made headlines also for the discovery of possible biosignatures in samples it collected last year, also from within Jezero crater.

These precious samples have now been cached in special sealed containers on the rover for collection by a future Mars sample return mission. Unfortunately, the mission has recently been cancelled by Nasa and so what vital evidence they may or may not contain will probably not be examined in an Earth-based laboratory for many years.

Crucial to this future analysis is the so-called “Knoll criterion” – a concept formulated by astrobiologist Andrew Knoll, which states that for something to be evidence of life, an observation has to not just be explicable by biology; it has to be inexplicable without it. Whether these samples ever satisfy the Knoll criterion will only be known if they can be brought to Earth.

Either way, it is quite striking to imagine a time on Mars, billions of years before the first humans walked the Earth, that a tropical climate with – possibly – a living ecosystem once existed in the now desolate and wind-swept landscape of Jezero crater.