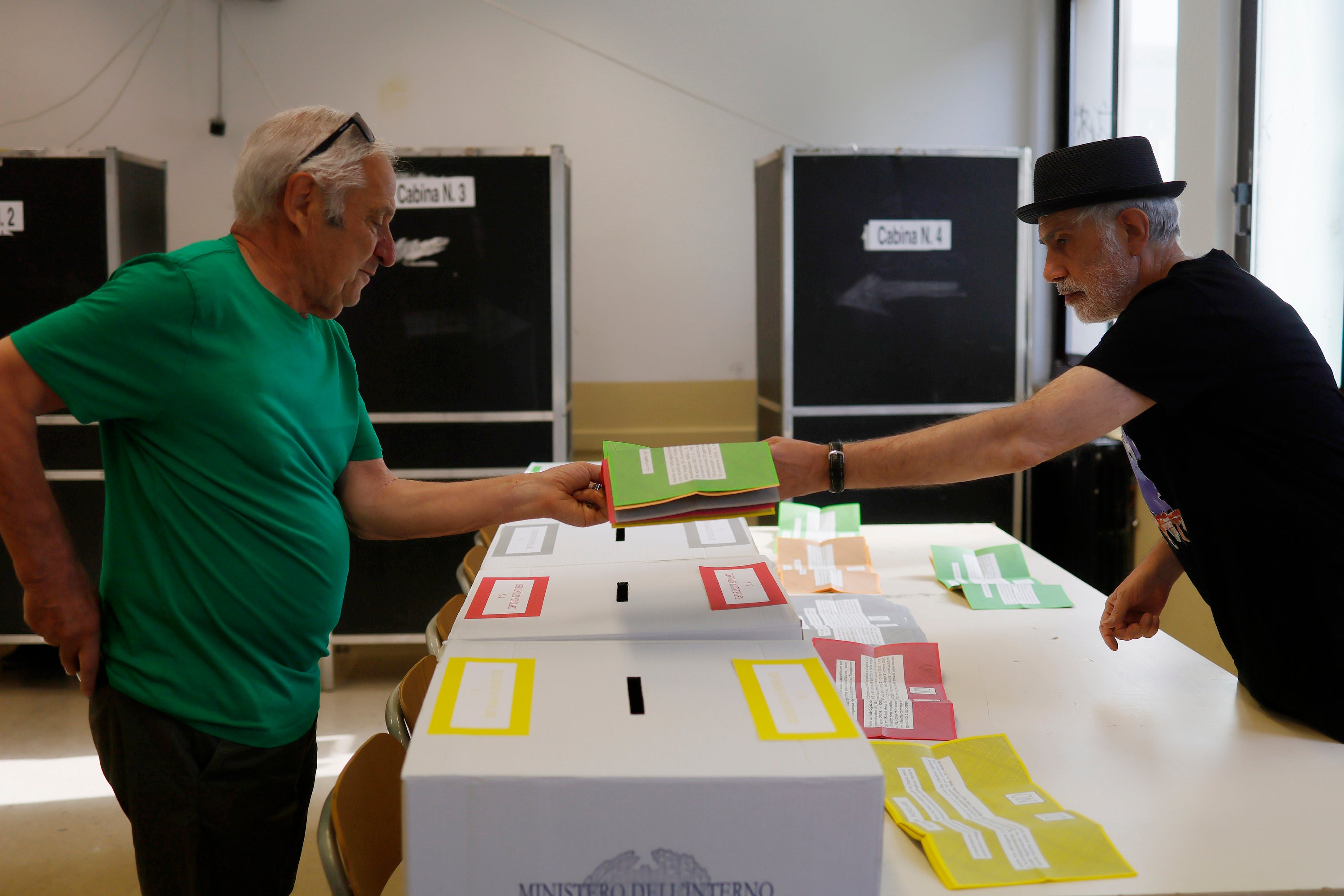

Italians have been voting in five referendums on Monday and Sunday regarding citizenship laws for children born in Italy to foreign parents, and on providing more job protections.

Early data indicates a low turnout, with just 22.7 per cent of eligible voters participating by Sunday evening, according to Italy’s Interior Ministry. This is just over half of the 41 per cent registered at the same time of day in a comparable referendum held in 2011.

One of the five referendums is about reducing the period of residence required to apply for Italian citizenship by naturalisation to five years from 10 years. This could affect about 2.5 million foreign nationals, organisers say.

With Italy’s birthrate in sharp decline, economists say the country needs to attract more foreigners to boost its anaemic economy, and migrant workers feel a lot is at stake for them as they seek closer integration into Italian society.

Campaigners say the change in the citizenship law will help second-generation Italians born in the country to non-European Union parents better integrate into a culture they already see as theirs.

The measures were proposed by Italy’s main union and left-wing opposition parties.

Premier Giorgia Meloni did not cast a ballot, an action widely criticised by the left as antidemocratic.

“While some members of her ruling coalition have openly called for abstention, Meloni has opted for a more subtle approach,“ said analyst Wolfango Piccoli of the Teneo consultancy based in London. ”It’s yet another example of her trademark fence-sitting.’’

Supporters say this reform would bring Italy’s citizenship law in line with many other European countries, promoting greater social integration for long-term residents.

It would also allow faster access to civil and political rights, such as the right to vote, eligibility for public employment and freedom of movement within the EU.

“The real drama is that neither people who will vote ‘yes’ nor those who intend to vote ‘no’ or abstain have an idea of what (an) ordeal children born from foreigners have to face in this country to obtain a residence permit,” said Selam Tesfaye, an activist and campaigner with the Milan-based human rights group Il Cantiere.

Activists and opposition parties also denounced the lack of public debate on the measures, accusing the governing center-right coalition of trying to dampen interest in sensitive issues that directly impact immigrants and workers.

In May, Italy’s AGCOM communications authority lodged a complaint against RAI state television and other broadcasters over a lack of adequate and balanced coverage.

Opinion polls published in mid-May showed that only 46 per cent of Italians were aware of the issues driving the referendums.

Turnout projections were even weaker for a vote scheduled for the first weekend of Italy’s school holidays, at around 35 per cent of around 50 million electors, well below the required quorum.

“Many believe that the referendum institution should be reviewed in light of the high levels of abstention (that) emerged in recent elections and the turnout threshold should be lowered,” said Lorenzo Pregliasco, political analyst and pollster at YouTrend.

Some analysts note, however, that the center-left opposition could claim a victory even if the referendum fails on condition that the turnout surpasses the 12.3 million voters who backed the winning center-right coalition in the 2022 general election.