Tens of thousands of centuries-old books are being urgently removed from a medieval abbey in Hungary in a desperate bid to save them from a devastating beetle infestation.

The 1,000-year-old Pannonhalma Archabbey, a sprawling Benedictine monastery and a UNESCO World Heritage site, is one of Hungary’s most ancient centres of learning.

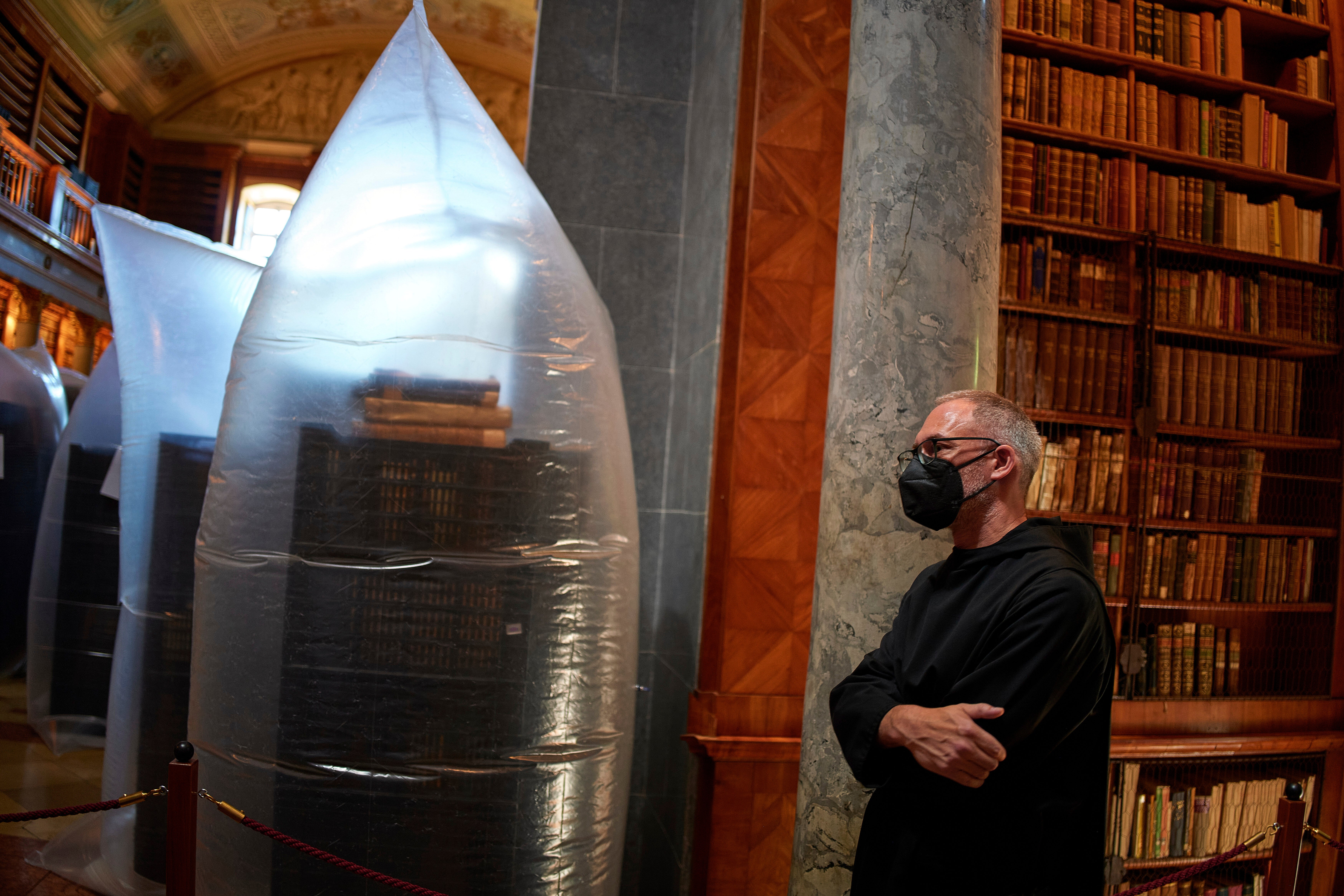

Restoration workers are meticulously pulling approximately 100,000 handbound volumes from the abbey’s shelves and are carefully placing them into crates as part of a disinfection process.

This aims to eradicate the tiny drugstore beetles, also known as bread beetles, which have burrowed into the historic texts.

The insects, commonly found among dried foodstuffs, are drawn to the gelatin and starch-based adhesives used in bookbinding.

The infestation has been discovered in a section of the library containing around a quarter of the abbey’s 400,000 volumes, threatening to wipe out centuries of accumulated knowledge.

“This is an advanced insect infestation which has been detected in several parts of the library, so the entire collection is classified as infected and must be treated all at the same time,” said Zsófia Edit Hajdu, the chief restorer on the project.

“We’ve never encountered such a degree of infection before.”

The beetle invasion was first detected during a routine library cleaning. Employees noticed unusual layers of dust on the shelves and then saw that holes had been burrowed into some of the book spines.

Upon opening the volumes, burrow holes could be seen in the paper where the beetles chewed through.

The abbey at Pannonhalma was founded in 996, four years before the establishment of the Hungarian Kingdom. Sitting upon a tall hill in northwestern Hungary, it houses the country’s oldest collection of books, as well as many of its earliest and most important written records.

For more than 1,000 years, the abbey has been among the most prominent religious and cultural sites in Hungary and all of Central Europe, surviving centuries of wars and foreign incursions such as the Ottoman invasion and occupation of Hungary in the 16th century.

Ilona Ásványi, director of the Pannonhalma Archabbey library, said she is “humbled” by the historical and cultural treasures the collection holds whenever she enters.

“It is dizzying to think that there was a library here a thousand years ago, and that we are the keepers of the first book catalogue in Hungary,” she said.

Among the library’s most outstanding works are 19 codices, including a complete Bible from the 13th century. It also houses several hundred manuscripts predating the invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century and tens of thousands of books from the 16th century.

While the oldest and rarest prints and books are stored separately and have not been infected, Ásványi said any damage to the collection represents a blow to cultural, historical and religious heritage.

“When I see a book chewed up by a beetle or infected in any other way, I feel that no matter how many copies are published and how replaceable the book is, a piece of culture has been lost,” she said.

To kill the beetles, the crates of books are being placed into tall, hermetically sealed plastic sacks from which all oxygen is removed. After six weeks in the pure nitrogen environment, the abbey hopes all the beetles will be destroyed.

Before being reshelved, each book will be individually inspected and vacuumed. Any book damaged by the pests will be set aside for later restoration work.

The abbey, which hopes to reopen the library at the beginning of next year, believes the effects of climate change played a role in spurring the beetle infestation as average temperatures rise rapidly in Hungary.

Ms Hajdu, the chief restorer, said higher temperatures have allowed the beetles to undergo several more development cycles annually than they could in cooler weather.

“Higher temperatures are favorable for the life of insects,” she said.

“So far we’ve mostly dealt with mould damage in both depositories and in open collections. But now I think more and more insect infestations will appear due to global warming.”

The library’s director said life in a Benedictine abbey is governed by a set of rules in use for nearly 15 centuries, a code that obliges them to do everything possible to save its vast collection.

“It says in the Rule of Saint Benedict that all the property of the monastery should be considered as of the same value as the sacred vessel of the altar,” Ms Ásványi said.

“I feel the responsibility of what this preservation and conservation really means.”