Winning an Oscar is the easy part. Getting up onstage and delivering an acceptance speech that doesn’t burn the internet down in an inferno of furious discourse? That’s where things get tricky. Just ask Graham Moore. On 22 February 2015, the novelist and filmmaker – who hadn’t told many people about the Sunday afternoon, aged 16, when he tried to end his life – found himself telling 37 million Americans about it all at once.

It was the 87th Academy Awards, and the Los Angeles-based writer had just won Best Original Screenplay for the Benedict Cumberbatch starrer The Imitation Game. As he made his way to the stage, the then 33-year-old knew exactly what he wanted to say. “I thought, if this is going to be the only time in your life that you’re before millions and millions of people, you better say something meaningful,” explains Moore, to whom it seemed “more ethical” to deliver a message to America’s outsiders and outcasts given the subject of his film. The Imitation Game had told the tale of British mathematician Alan Turing – a man whose brilliance helped win the Second World War for the Allied forces, but whose sexuality meant he was still condemned to a brutal fate.

The idea of “standing on that stage in a tuxedo, being handed a gold trophy for writing about a life that ended so tragically” made it feel “almost obscene” to make the moment about himself, Moore explains. And so began a rallying cry, using the story of his darkest day as a reminder to any “kid out there who feels like she’s weird or she’s different or she doesn’t fit” to hang in there – to “stay weird, stay different,” as he put it onstage at Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre.

Online, commentators applauded his bravery and pondered the potential positive impact; suicidal ideation, after all, was a taboo topic seldom discussed openly, let alone on Hollywood’s biggest night. “Inspiring” was Buzzfeed News’s response. Then, a backlash began to mount. “Alan Turing wasn’t ‘weird;’ he was a brilliant gay man who killed himself because his government chemically castrated him,” author Ira Madison III reacted in that same publication a day later, accusing Moore (who’s straight) of doing a “disservice” to the mathematician’s memory by not addressing the struggle of the LGBT+ community specifically in his speech. Other think-pieces followed. It’s a tale that points to the difficulty (and perhaps even impossibility) of writing an Oscar speech that doesn’t stoke some sort of controversy – then and now, perhaps more than ever.

Acceptance speeches are one of Oscar night’s oldest traditions – and most reliably controversial, too. In 2003, Michael Moore was booed offstage after protesting the Iraq war while accepting Best Documentary for gun control film Bowling for Columbine. Before him, there was Vanessa Redgrave, who labelled the far-right Jewish Defence League “Zionist hoodlums whose behaviour is an insult to the stature of Jews all over the world” onstage in front of the Academy in 1978, during her Best Supporting Actress acceptance speech for the drama Julia. And from Sean Penn and Patricia Arquette to Marlon Brando and Joaquin Phoenix, there’s a long and storied history of performers and artists whose speeches sent shockwaves through pop culture.

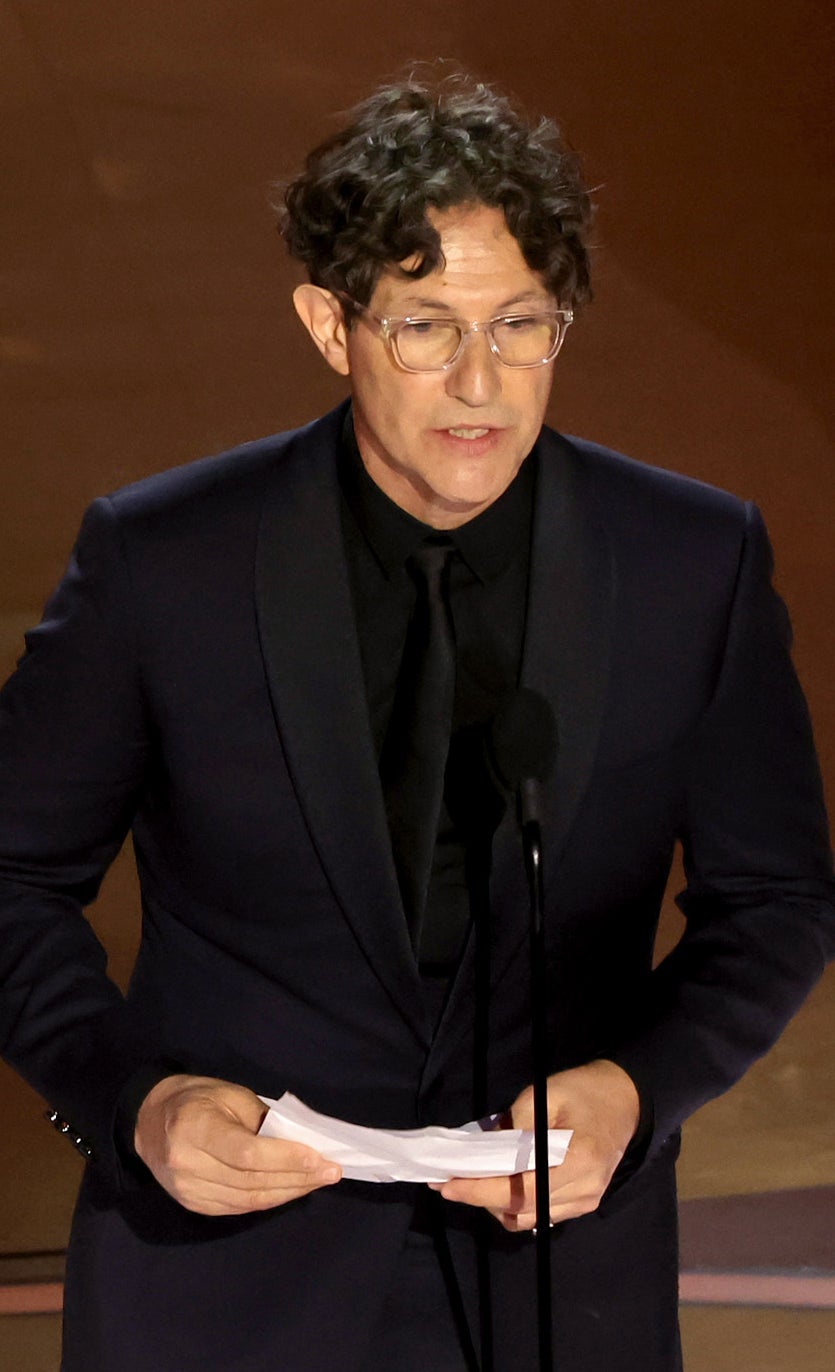

Last year, The Zone of Interest director Jonathan Glazer became the latest addition to that list. “Jonathan’s an interesting example of the difficulty of acceptance speeches specifically in the age of the internet and social media,” one major Hollywood publicist, speaking anonymously to protect her clients’ chances of success at this year’s Academy Awards, tells me. “You used to be damned for what you did say. Now you’re damned also for what you don’t say, too,” they suggest – a nod to how during 2024’s awards season, as Glazer’s Holocaust drama began to pick up awards at events like the Baftas, online condemnation grew over his relative silence about Gaza. Why wasn’t this filmmaker, who’d made a movie about the mass death of one group of people, speaking out on the perceived parallels between his film and what was happening in the Middle East, pro-Palestine activists lamented?

Glazer did eventually speak out, sparking fury from pro-Israel supporters within Hollywood. The whole episode was revealing of a change in what the public demand of celebrities in 2025, says the same publicist. “Artists are now expected to use their platform to speak out about social injustices, [making speeches as much about] what’s not said as what is,” they explain. “It’s honestly a minefield. And a great source of stress. How do [publicists] advise on that?” With this year’s Academy Awards taking place not just in the shadow of the continuing wars in Gaza and Ukraine, but also in the wake of Donald Trump’s second term in the White House, that minefield promises to be harder to navigate than ever for prospective Oscar winners this year.

“I personally can’t imagine having that stage, with that [big an] audience, while living in a country descending into oligarchical fascism… and not saying something,” says Adam McKay, writer-director of Anchorman, Step Brothers, Vice and Don’t Look Up. In 2016, his comedy The Big Short won Best Adapted Screenplay. What followed was a speech that took aim at political corruption in a bracing way: “If you don’t want big money to control government, don’t vote for candidates that take money from big banks, oil or weirdo billionaires,” he urged voters onstage.

“After making a movie like The Big Short, it would have felt fairly gross not to say something about the big money that cost so many people their homes and lives,” he continues, recalling how he was “pretty nervous” ahead of the speech. That was 2016. This year is a time in which the “climate is breaking down because of oil companies’ greed and [approximately 50,000] mostly women and children were just killed in Gaza with American bombs,” the filmmaker adds. Should Oscar winners ignore that context this year, something would feel strange, he suggests. “Talk about not reading the room-slash-planet-slash-human historical timeline. But it’s each person’s choice.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

Will Hollywood’s biggest and brightest stars heed McKay’s advice and speak out at this year’s event on 2 March? On one hand, nominees may be more guarded about appearing to mount a soapbox after an election that saw the American electorate ignore Hollywood stars’ pleas to cast their ballot for Kamala Harris. “You should be quiet, you should do your job, you should… entertain people – then shut the f*** up,” said actor Gabriel Basso last week, five years after playing future vice-president JD Vance in the Ron Howard film Hillbilly Elegy. His comments are thought to be reflective of a new awareness in the entertainment industry – that there’s a huge portion of the population who view actors and directors as out-of-touch members of a liberal elite (see also: Dwayne Johnson’s recent promise to “keep my politics to myself” after previously being an advocate for progressive causes).

On the other hand, the problems at the heart of a lot of the films nominated are urgent, and to ignore them in fear of potential backlash would be ignoring one hell of an elephant in the room. Can Brady Corbet really pick up Best Picture for immigration epic The Brutalist without mentioning the terror many immigrants are living under right now in the United States, as law enforcement agencies raid schools and workplaces across the country? What would it mean for Zoe Saldaña to pick up Best Supporting Actress for trans musical Emilia Pérez without addressing the fact that trans people in America are right now watching their history erased and their rights revoked in sweeping executive orders issued by President Trump?

Graham Moore, for his part, would do it all again if he were taking the stage today. “I don’t think I would say a single thing differently,” he says. “I think the issue of people feeling excluded from mainstream society – for their sexuality, for their gender, for whatever reason it might be – hasn’t changed in the last 10 years. In many ways, it’s gotten worse. And so I think what I endeavored to do, and what I would do again, is say: ‘Look, here’s something that happened to me. I tried to kill myself when I was a teenager. And here I am now. Do with this personal story what you will.’”

His 45 seconds onstage at the Oscars a decade ago sparked weeks of debate. Whoever wins at this year’s ceremony and whatever they do (or don’t) say in the speeches that follow, expect more of the same – an inferno of furious discourse is inevitably about to spark.

Amendment: An earlier version of this article quoted Adam McKay as saying “half a million mostly women and children were just killed in Gaza with American bombs.” Palestinian health authorities estimate that the total number of people killed by Israel’s ground and air campaign in Gaza is around 50,609.