An experimental drug appears to reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s in people “destined” to develop the disease in middle age.

The study, published in the journal The Lancet Neurology, involved 73 people with rare, inherited genetic mutations that cause the overproduction of the protein amyloid in the brain. This all but guarantees they will develop Alzheimer’s disease in their 30s, 40s or 50s.

For 22 patients who had no cognitive problems at the start of the study, and who received the anti-amyloid drug the longest – an average of eight years – the treatment lowered the risk of developing symptoms by half.

The results boost hopes similar treatments being developed to target more common forms of Alzheimer’s – that appear when people reach their sixties, seventies and eighties – might also be effective.

These findings provide new evidence to support the theory that amyloid leads to Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s thought amyloid forms toxic plaques around brain cells and as the brain becomes affected, there is also a decrease in chemical messengers, called neurotransmitters, involved in sending messages between brain cells.

The study suggests removing such plaques or stopping them form forming can prevent symptoms of the memory robbing disease.

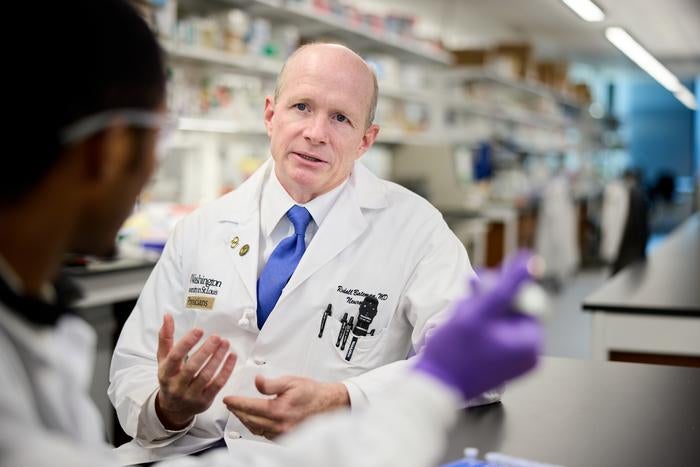

“Everyone in this study was destined to develop Alzheimer’s disease and some of them haven’t yet,” said senior study author Randall Bateman of Washington University in St Louis, Missouri.

“We don’t yet know how long they will remain symptom-free – maybe a few years or maybe decades.

“In order to give them the best opportunity to stay cognitively normal, we have continued treatment with another anti-amyloid antibody in hopes they will never develop symptoms at all.

“What we do know is that it’s possible at least to delay the onset of the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and give people more years of healthy life.”

The study participants consisted of people who had originally enrolled in the first Alzheimer’s prevention trial in the world, launched in 2012, and then continued into an extension of the trial in which they received an anti-amyloid drug.

All participants in the trial had no-to-very-mild cognitive decline and were within 15 years before to 10 years after their expected age of Alzheimer’s onset, based on family history.

When the initial trial concluded in 2020 researchers reported that one of the drugs, gantenerumab, lowered amyloid levels in the brain.

But the researchers did not see evidence of cognitive benefit then because the group without symptoms – regardless of whether they were on drug or placebo – hadn’t cognitively declined.

As a result, the researchers continued to study the drug to determine whether higher doses or longer treatment could prevent or delay cognitive decline, and found it could reduce the risk of developing symptoms from 100 per cent to 50 per cent.

Gantenerumab is no longer made by Roch, the company that developed it, because it did not slow symptoms of a more common non-genetic form of Alzheimer’s in a trial of 1,900 participants.

But there are other anti-amyloid drugs being developed.

Although the trial was limited to people with genetic forms of Alzheimer’s that lead to early onset, researchers expect that the study’s results will inform prevention and treatment efforts for other forms of Alzheimer’s disease.

Both early-onset and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease can start with amyloid slowly collecting in the brain two decades before memory and thinking problems arise.

Dr Richard Oakley, associate director of research and innovation at the Alzheimer’s Society, and who was not involved in the study, said it showed there is “hope on the horizon” to beat Alzheimer’s.

“These exciting early-stage results hint that long-term anti-amyloid treatments, started before Alzheimer’s disease symptoms appear, could potentially delay symptom onset,” he said.

“However, these results need to be treated with caution; this trial focuses on a very small group of individuals with genetic forms of Alzheimer’s disease. Longer-term follow up of this group and larger studies will tell us more about the effect of these drugs in these types of Alzheimer’s.”