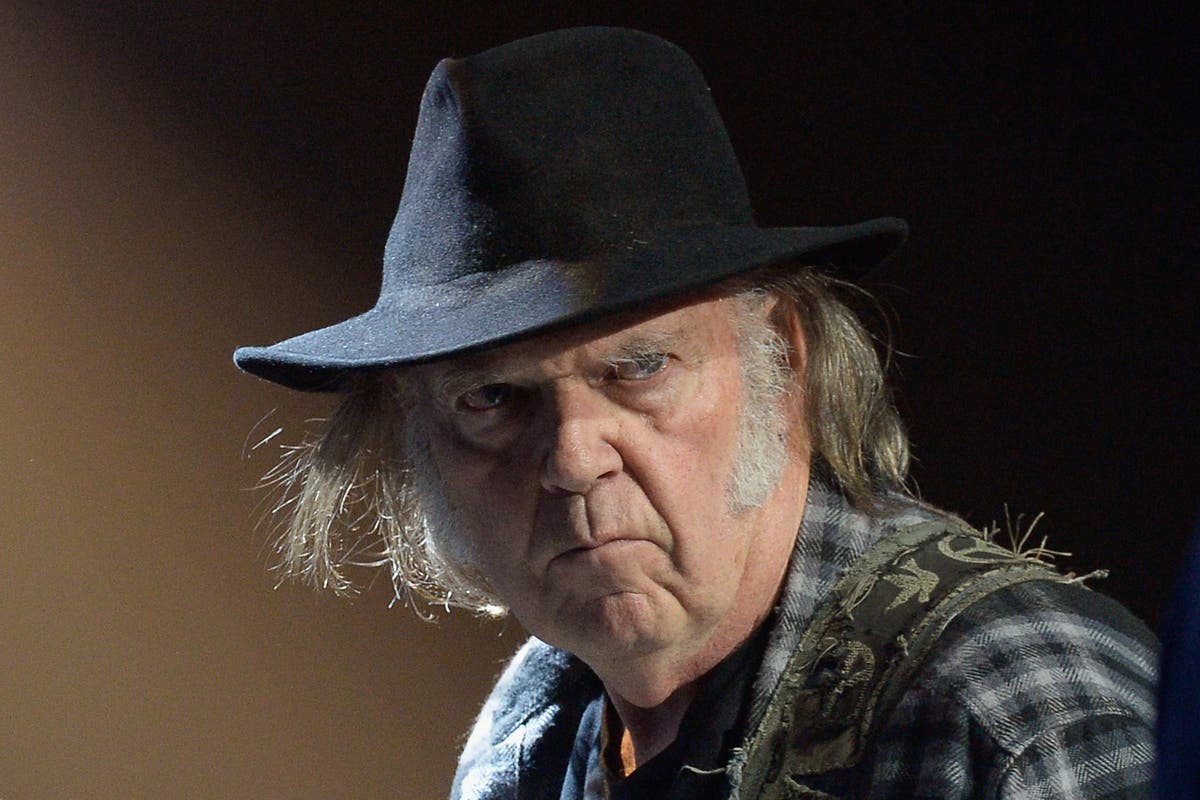

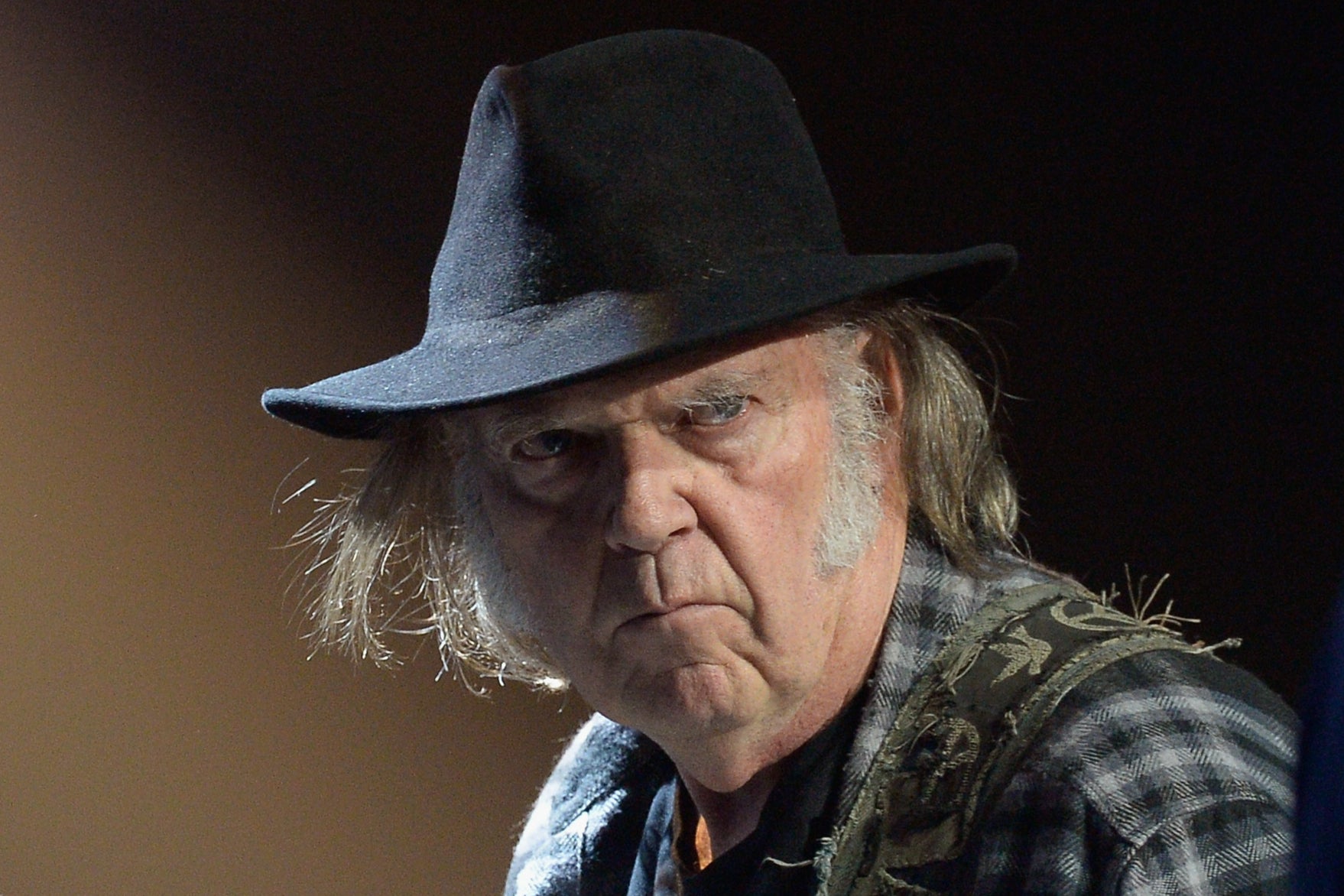

Neil Young has had it with the gold rush. The Canadian singer-songwriter, 79, had been strongly tipped to headline Glastonbury Festival this year, his first appearance since 2009. In a statement on his website this week, Young confirmed that the rumours were legit, before dashing fans’ hopes. “We were told that BBC was now a partner in Glastonbury and wanted us to do a lot of things in a way we were not interested in,” he wrote. “It seems Glastonbury is now under corporate control and is not the way I remember it being.”

While the “Heart of Gold” musician didn’t specify what demands the BBC had made, many assumed the dispute had to do with televising Young’s set. (For his 2009 headline performance, Young negotiated an agreement whereby only five of his songs would be broadcast on TV, thus “retaining the mystery” of the live event. Other artists, such as David Bowie and Elvis Costello, had previously insisted on similar deals.) And then, just two days later, there was a reversal: Young released another statement, saying that there had been “an error in the information received”, and his 2025 Glastonbury performance is now set to go ahead. It’s welcome news for Young fans and festivalgoers at large. But the impact of the (admittedly vague) criticisms he made might not dissipate so quickly.

The fact is, modern-day Glastonbury is under corporate control, to some extent. But that’s just an inevitability. It would be impossible to stage a festival on the scale of Glastonbury without corporate involvement. There’s too much money involved, too much infrastructure required. The BBC’s extensive coverage of the festival – last year over 90 hours of performance footage was released by the broadcaster, across terrestrial channels and iPlayer – is obviously self-serving, providing both high-profile programming for the Beeb and lush, persuasive advertising for next year’s festival. But it’s something that also serves music fans, giving those unable to attend the festival the chance to get a flavour of what they’re missing. More than 20 million people now tune in to watch the BBC’s Glastonbury coverage each year. After nearly 30 years on the BBC, it is something people expect to see on television. Everyone wins.

Glastonbury might be more corporate than ever, but it is also – in this sense – more accessible. (Some, of course, would argue that rising ticket prices have actually made the festival less accessible for many. On this I would say that Glastonbury organisers can only shoulder so much blame – ticket prices have shot up industry-wide, and are partly an unavoidable response to the evolving expectations and demands of festivalgoers when it comes to infrastructure and amenities.) And of all the possible broadcasting partners the festival could have, the BBC is at least state-owned, and unbeholden to advertisers. If Glastonbury were airing on Channel 4 – as it did between 1994 and 1997, before the rights transferred over to the Beeb – then there would be a whole other set of corporate considerations; likewise if the rights were purchased by Amazon, or Netflix.

Concerns that Glastonbury’s TV coverage risks compromising the integrity of the live music experience are not without some merit. There is something to be said about the immediacy of a live gig, and television’s inability to capture or replicate that. But this is rather the point – no one is going to give up their Glastonbury ticket because it’s showing on TV, and no one at the festival is going to have a materially worse experience because there are cameras there. Besides, it’s 2025, and a Neil Young Glastonbury performance is always going to be recorded and released online, whether he likes it or not: even if the BBC weren’t covering it, it would doubtless be filmed, recorded and uploaded onto YouTube by his fans anyway. Allowing for proper camera equipment only makes the experience better for people who love his music.

It’s not surprising, perhaps, that Young should be prickly about this subject: he was, after all, once part of the hippy movement, and the moral idealism that accompanied it. Glastonbury was born out of this same zeitgeist, and was rooted in socio-political radicalism, the kind of anti-commercial thinking that surely would have balked at the BBC’s organisational involvement. But that was a long time ago, and the hippy revolution is now long dead. Glastonbury still indulges its countercultural beginnings, but the festival at large has been shaped and altered by compromise.

This hangover of hippy idealism might also be what led Young to remove all his music from Spotify in 2022, in opposition to the streaming service’s platforming of Joe Rogan’s controversial Covid-conspiracy-mongering podcast. Two years later, Young called an end to the boycott. He hadn’t won; Rogan had simply expanded his podcasting deal to other platforms, so continuing the boycott would have involved Young removing his music from all the biggest streamers. “Because I cannot leave all those services like I did Spotify, because my music would have no streaming outlet to music lovers at all, I have returned,” Young wrote. It’s not a morally consistent course of action, but it is a pragmatic one – a decision that takes into account the practicalities of contemporary music distribution, and the importance of making his back catalogue accessible.

It is this attitude that Young – and other artists uneasy with Glastonbury’s corporate underpinnings – ought to take when it comes to the UK’s biggest festival: one of pragmatism and adaptability. The Glastonbury of old is gone, and it’s never coming back. But that doesn’t mean that what’s grown out of it can’t be special too.