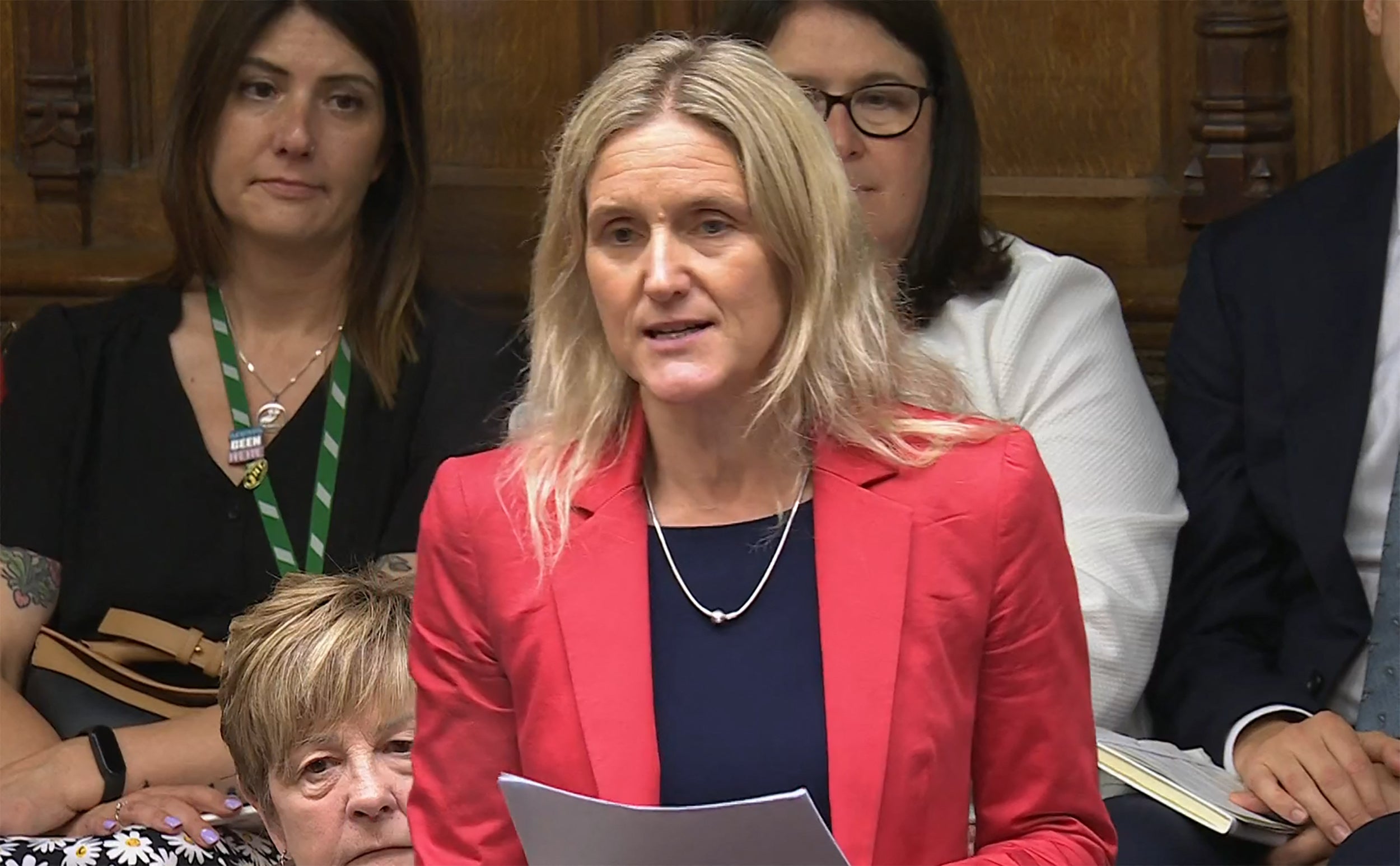

It takes something unusual to get an almost full attendance in the House of Commons on a Friday – and that unusual, potentially epoch-making event was the decisive third reading of Kim Leadbeater’s bill to legalise assisted dying, or as formally entitled, the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill.

I have a particular, and very personal, perspective on this. I believe this bill, in its original form, and still less as amended, falls very far short of legalising assisted dying for very many of those who might have been pinning their hopes on it.

So limited is its scope, in fact, that it will positively exclude many of those – such as my late husband – who have been the most determined in arguing for a right to choice at the end of life.

The only people empowered to take advantage of the new law will be those judged by doctors to have less than six months to live. That will automatically rule out many, perhaps most, of those with chronic, progressive conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease, or – in my husband’s case – Parkinson’s disease – some of the very people who have been campaigning most passionately for legalised assisted dying.

How many doctors will commit to pronouncing that someone with – say, Parkinson’s – has only six months of life left, knowing that this will be a licence for an assisted death? Almost none, I would submit.

The pace of such progressive diseases can be unpredictable. Some, such as Parkinson’s, may fluctuate, while always on a downward trajectory. Those with terminal cancer may be among the very few able to take advantage of the law change. Even then, the time taken up by panels and paperwork, as required by the bill, could take up an undue portion of the six months the applicant is deemed to have left.

But let me set out my husband’s arguments, which will echo those of many others. He (and I) had watched his mother’s decline and death from Parkinson’s. He knew, from the moment of his diagnosis, pretty much what lay in store, with the difference that he was diagnosed in his mid-forties and it affected primarily mobility, without the characteristic tremor. Drugs can control the condition in its early stages, and more so today than three decades ago, with glitches when medication needs to be increased or changed.

As the disease progresses, the amount and complexity of medication brings problems of its own in the form of side effects. There comes a point where the sufferer may find the side effects as bad, or worse, than the acute tremor, pain or mobility difficulties caused by the disease.

My husband reached that point in the early 2000s, a time that happily coincided with some of the first brain implants – deep brain stimulation, which functions a little like a heart pacemaker to replace electronically the missing dopamine in the brain. The operation tends to be more successful in arresting tremor; the outcome is more mixed for those, such as my husband, whose Parkinson’s primarily affects mobility. Pluses and minuses, but it drastically reduced the amount of medication he needed, and so some of the side effects, and I would gauge, gave him an extra seven years of reasonably enjoyable life.

Nikolai was utterly determined to have the DBS operation, fully recognising the then considerable risks. There was no point in trying to dissuade him. His great fear was of becoming helpless – remaining conscious, mentally alert (which he was to the end), but immobile, mute, and unable to do anything for himself. This is also why, practically from the time of his diagnosis, he became a supporter of Dignity For Dying, the charity that has long lobbied for assisted dying, and took every opportunity to insist that, when he judged the time to be right, he wanted to go to Dignitas, if there was still no legal assisted death in the UK.

He was adamant and very clear about what he wanted – and didn’t want. Yes, it was partly about control, but it was mainly about gradually losing so much of what made his life worth living. (The loss of dexterity sufficient to operate even an adjusted keyboard was one landmark, as was the decline in his speech.) And I would have taken him to Switzerland – probably by car, as the last of the road trips we used to take in Europe.

I would also have been prepared to defend myself in court, should that need arise, as others in a similar position have done. I am not a natural law-breaker, but I would have had no hesitation in following that course. It should also be stressed that what amounts to a freedom to choose extends only to those with the means and the physical capability to make that journey to Zurich.

I am well aware of the counterarguments to the current bill, and to assisted dying in principle and in practice. There is the risk that someone decides on an assisted death, when the diagnosis is wrong. There is the variable (to put it mildly) quality of palliative care, and the largely paid-for social care system in England that could cause sufferers to feel obliged, or be pressurised by potential beneficiaries of their estate to protect the inheritance. (And to anyone who denies that this is a risk, just read all the accounts of disputed wills that regularly appear in the media).

The most compelling contrary arguments – to me, at least – are those about the sanctity of life, that it is for “man to propose and God to dispose”, which are common to many religions. I also understand, while not quite accepting, the view that assisted dying implies an undervaluing, even dismissal, of people who are disabled or ill.

As it happens, I have a cousin, Reverend Michael Wenham, a retired teacher and Church of England vicar, who represents these counterarguments with admirable conviction and clarity (See My Donkey Body, and many articles). I would never argue that assisted dying should be, or become, anything more than a fully informed and personal choice.

I also have qualms about doctors who argue that their Hippocratic Oath says “do no harm”, and assisting someone to die amounts, as I heard one say recently, “to the ultimate harm”. To me, an equal harm is to “strive officiously to keep someone alive”, which is what modern medicine, too often, allows.

In the event, I was spared the agonising trip to Zurich. Seven years ago, my husband suffered a cardiac arrest while we were on holiday in Sicily. A mediaeval historian, he had spent some of the morning happily looking at the Norman tombs in Palermo cathedral, and died in the evening, within minutes of his collapse, for all the heroic efforts of the Italian ambulance crew, to revive him.

In many ways, it was the perfect end, in the perfect setting – and the Italians, from the medics to the police to the undertakers, were exemplary, assisted by my nearly bilingual sister, who flew in the next day from southern Italy where she has lived for more than 40 years.

That many of those who would opt for an assisted death, if it became legal, will depart this life, as my husband did, before the need arises to act on their wishes, does not diminish the fundamental argument. There is an urgent need for assisted dying to become a choice that does not depend on possessing the means to get to Dignitas in Zurich or risk a close friend or relative ending up in court.