Tonight, more than 2,500 people will spend yet another night in prison serving the long-abolished IPP sentence – the sentence of Imprisonment for Public Protection. Some of these people have been in prison for 20 years.

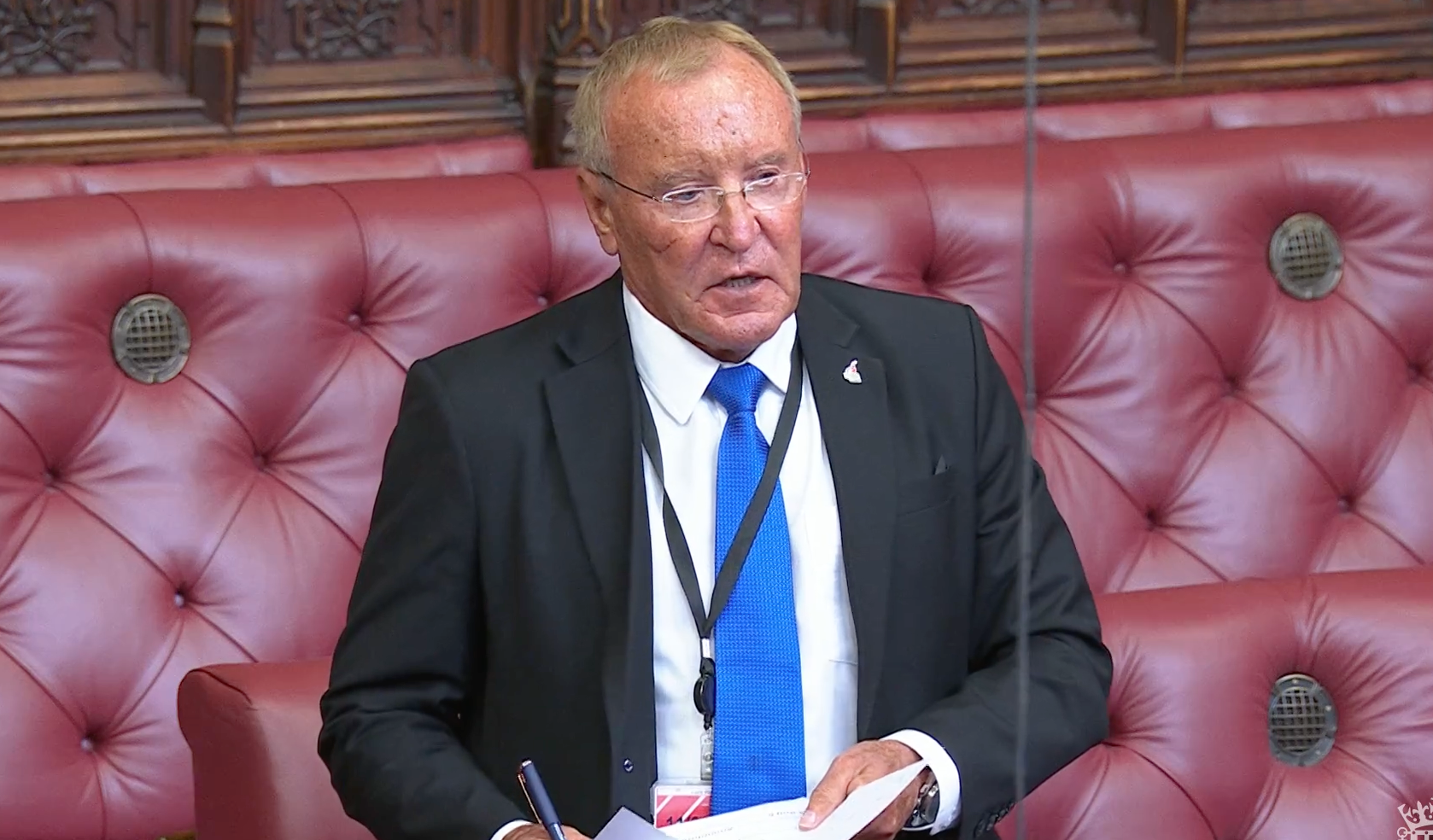

On Friday, as the Labour peer Lord Tony Woodley’s private member’s bill to resentence IPP prisoners reached committee stage in the House of Lords, peers urged prisons minister James Timpson to take decisive action to end the injustice of IPP jail terms.

Everyone familiar with the IPP sentence has a shared understanding of the ravages of this sentence. We are committed to ending its impact on people in prison, as well as the merry-go-round of recall to prison for people on IPP licences in the community. And yet, there is no agreed route to making this happen.

The IPP sentence was established in 2005 by the last Labour government. It required an individual to serve a specified term, after which time they would need to apply to and be released by the Parole Board. Despite expectations that IPP would be used sparingly, it was used to imprison 8,711 people, including hundreds of children who received an equivalent Detention for Public Protection (DPP) sentence. Because the Parole Board release test is very high – intended for those who have committed the most serious offences – it has proved difficult for people serving an IPP sentence to secure release.

The sentence was abolished by the coalition government in 2013, though not retrospectively. There are just over 1,000 people who have never been released, of whom more than 700 are a decade or longer over their tariff.

I recently met a young man in a Midlands prison who had received a two-year DPP as a 15-year-old. He has now spent more than half his life in prison. He was released a couple of years ago, only to be recalled to custody earlier in the year for being late to probation appointments, which clashed with his employment. Again behind bars, he felt he ‘can never escape the torture of the sentence.’

In 2022, the Justice Select Committee recommended a resentencing exercise, but with a vast majority of IPP prisoners significantly over tariff, most would need to be released immediately and without a licence. The government at the time rejected this solution on the grounds of public protection, as has the current government.

It is worth remembering that the IPP sentence is not for a specific offence. These people were just given an indeterminate sentence, while other people who committed similar offences were given determinate sentences and released years ago. People released on an IPP sentence also don’t have a huge propensity to violence or crime; more people on IPP sentences have died by suicide in the community than have gone on to commit serious further offences.

While a recent change to licence termination greatly helped those people serving IPP sentences in the community, it did nothing to accelerate the release of people who have never been released.

In this context, late last year, the Howard League formed an expert working group, led by former Lord Chief Justice, Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd, and charged with finding a way to release those people serving an IPP or DPP sentence while meeting the government’s legitimate concern for public protection.

The group reported last week with six key recommendations that would finally give all IPP prisoners a certain release date within two years via a change to the Parole Board release test, providing a runway to release for everyone serving an IPP sentence, while including safeguards for public protection. Other recommendations include providing greater support to IPP prisoners on release and reducing unnecessary recall of people to prison.

The government is clear that it will not resentence people on the IPP. But it cannot do nothing. The status quo, which is the delivery of the last government’s “Action Plan,” does not end the sentence and just feeds despair. While the prison service is doing its best, it is unreasonable to expect staff to deliver change for the IPP population in the context of a prison overcrowding crisis.

History shows that governments invariably find it difficult to remedy state wrongs, but people on the sentence and their families don’t have time to wait for a Mr Bates vs The Post Office–style TV series. The IPP sentence is a state wrong which the government has a responsibility to right. The fact that thousands of people remain in prison under the IPP sentence brings shame upon our legal system. The government needs to act urgently.

Andrea Coomber is chief executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform