What was more exhausting, I ask Keira Knightley: that five-year period in her career when she made a bazillion massive films, including Bend It Like Beckham, Atonement, Pirates of the Caribbean, Pride & Prejudice and Love Actually, or… early motherhood? “Early motherhood!” she answers instantly, without a blink. “There is nothing that can prepare you for that level of exhaustion if you happen to have a sleepless child.”

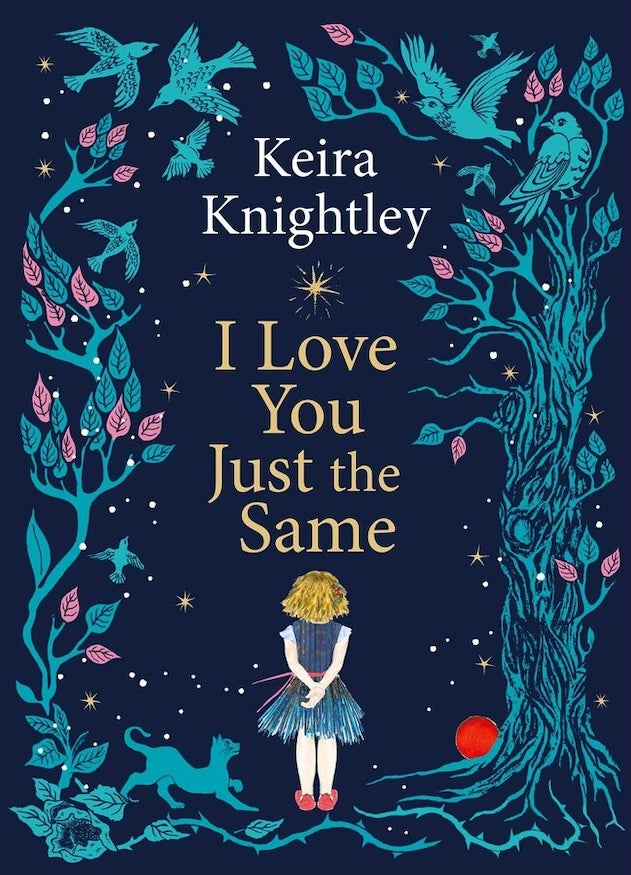

Knightley, 40, and her husband, the musician James Righton, tried “everything” to get their first daughter Edie, now 10, to sleep through the night. They finally succeeded with a very lovely bedtime routine, which has now, years later, resulted in something completely unintended but quite special: Knightley’s debut children’s book, I Love You Just the Same. Over a five-month period, Knightley would draw a picture every time Edie went to sleep, so that when she woke up, she’d know her mum had been thinking of her. “It turned into a kind of dialogue between us, where she’d say, ‘OK, can there be a bird? Can there be a cat?’”

Which helps to explain Knightley’s cross-generational appeal. To us, she is one of the defining stars of British film from the past 25 years. But in the eyes of my daughter – who at eight months old is very partial to the actor’s feline illustrations – she is simply the lady who drew the cat. Is this new guise the reason I don’t recognise Knightley when I first arrive to meet her at a cafe in North London? She’s so inconspicuous that when the waiter asks if the woman in the stripy shirt with the brown bob is the person I’m looking for, I say no, until a familiar face leans round, mouthing: “Are you…?” and I realise that, actually, she is. Only when I’m sitting opposite her does it all come into focus: the film-star face; the makeup-less but luminous skin; the truly, truly great eyebrows.

Knightley has perfected the art of blending in. In 2002, her breakout role in the football-based Brit flick Bend It Like Beckham brought a cascade of lead parts and an unbearable level of tabloid scrutiny. As a teenager, she endured the bruising experience of becoming one of the most famous women in the world, tormented by paparazzi and picked apart in the press. To those of us who had watched Knightley grow up, her admission in 2018 that she’d had a breakdown aged 22 made depressing sense.

Since then, she’s slowed down and gracefully ducked the spotlight. Nurturing a respected career on her own terms, she continually makes interesting choices, from playing Alan Turing’s codebreaker confidante Joan Clarke in 2014’s The Imitation Game (for which she received her second Oscar nod) to starring as the trailblazing French author Colette in a 2018 biopic, and, more recently, as a government minister’s wife and secret agent in Netflix’s Christmassy gorefest Black Doves.

Now, she’s doing something no one expected: publishing a children’s book. When her foray into fiction was announced last year, the news was met with a backlash from kids’ authors worried about entitled A-list pretenders on their turf (Matthew McConaughey, Channing Tatum and the Duchess of Sussex are among the celebs to have dabbled in the genre).

Knightley acknowledges the criticism. “I mean, it’s going to happen. And I hear it, you know? I think it’s like in any creative industry, the space for anyone is very hard – if it’s actors, if it’s musicians. I’m sure it’s the same for writers. So I have sympathy for it.”

But it would be wrong to dismiss Knightley as just another star cynically cashing in on the kids’ books boom. Inspired by Edie and her younger daughter Delilah, now six, I Love You Just the Same is the delicately drawn, touchingly personal story of an older sister adjusting to the arrival of a new baby. It’s written with the understanding that the greatest children’s literature is stuffed with darkness and peril, the seed of the story coming from a request Edie made when her little sister was teething and crying all day: “She was like, ‘Can you draw a picture of the bird taking the baby away?’”

Meeting Knightley, I feel it’s on brand that she celebrated her 40th birthday making knives with her husband in a forge in North Wales. There’s a breezy friendliness to her conversation that belies an inner steel – the same kind that runs through the veins of her portrayal of Elizabeth Bennet, a character who will charm her way through a dull ball but shoot an icy glare at injustice or imbecility. (It was that role in Pride & Prejudice that landed Knightley her first Oscar nomination at just 20.) She laughs readily at most things, and gives the sense that she knows what you’re going to say before you do – and has already thought it through.

When I ask if anything makes her nervous about raising girls, she shoots back, “What, you mean social media?” Knightley is happy to admit she doesn’t know the answer to society’s most anxiety-inducing parenting conundrum. “At the moment, they’re not allowed on any of it, which… I don’t know if that’s right. If we can hold out until they’re 16, then I will desperately try and do that. I’ve no idea if that’s the right thing to do, or if we’ll succeed in doing that.”

It’s part of Knightley lore that she was born because her father, the actor Will Knightley, told her mother, the playwright Sharman Macdonald, that they could only afford to have another baby if Macdonald sold a play. She did: When I Was a Girl, I Used to Scream and Shout premiered at the Bush Theatre in 1984, and Knightley was born the year after. Every generation of mothers hope their daughters will have some of the things they didn’t, so what has Knightley benefited from that her mother had to go without? “A very regular income!” she exclaims. As for her own daughters, she hopes they’ll get “equal pay for equal work – 100 per cent, I would really like to see that happen within my lifetime and my children’s lifetime”.

Knightley doesn’t name the specific projects where she was underpaid – “I don’t ask; I find it easier not to” – and caveats the topic with an acknowledgement of her own relative privilege. “I know I’ve got [equal pay] a couple of times, and my agents have been very excited,” she says. “You know, I’m incredibly lucky with the work that I do. I’m incredibly lucky with the money that I’ve managed to earn from it. I know I haven’t earned anywhere near what my male counterparts have earned. I have nothing to complain about, equally, so I’m incredibly aware of how lucky I’ve been.” Her wish for equal pay applies to professions across the board – including her daughters’ current dream jobs of florist and sweetshop owner.

One of her first big screen roles was in the grungy indie horror film The Hole opposite Thora Birch and… Laurence Fox (it was 2001). The film has since become notorious for the fact that Knightley – just 15 when it was made – briefly flashes her boobs in one scene. She doesn’t remember much about the decision-making around that. “I remember liking doing the job. Definitely did flash my boobs though! I think I felt fine about it,” she says with a shrug. “I always had a sense that an actor uses their body for the job that they’re doing. I don’t remember feeling anything negative about it at all.” That said, she laughs, “Would I let my 15-year-old do that? No!”

Reports a few years ago that Knightley wouldn’t make any more sex scenes with male directors were a misrepresentation of her words. “No – ultimately I don’t have that kind of clout,” she explains. “I was saying that the male gaze doesn’t interest me as much as the female gaze.”

Speaking of the male gaze, I admit that when I rewatch Atonement I can’t help but think how uncomfortable Cecilia would have been during that infamous library liaison with Robbie, wedged up against an old bookcase. “That would be really uncomfortable,” Knightley nods, before adding impishly, “and I bet she didn’t come.” Even so, Knightley says, it was the best sex scene she’s ever done. “Now you go on [set] and it’s very much, ‘This is what we need, this is how we’re doing it, are you comfortable?’” she says, “which is exactly what Joe [Wright, the director] did back then.”

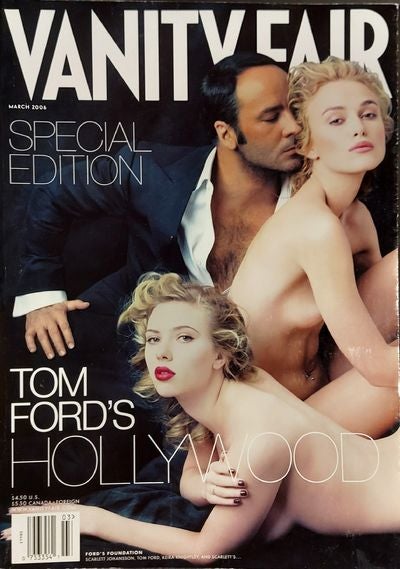

Perhaps the most surreal illustration of Knightley’s fame in the early Noughties was her appearance on the controversial cover of Vanity Fair’s iconic Hollywood issue in 2006. As part of the annual lineup of the year’s hottest stars, this edition featured a nude Knightley and Scarlett Johansson alongside a fully clothed Tom Ford sensuously sniffing a faceful of Knightley’s hair. “It was very of that moment, but it was also amazing,” Knightley says of the image. “It was saying exactly what it was. The man is in the suit, and the young women are meat. And it looked like that. And [Annie Leibovitz] photographed us like that. And that is what it was saying, and that was true.”

She remembers it with a wry twinkle. “I was 21; I mean, if you’re ever gonna get your kit off, it’s one of the best photographers in the world, for that magazine,” she joshes. “I remember it as being a really nice day. I really got on with Scarlett Johansson. It’s the one and only time I’ve ever met her. And we had a really nice day and a nice chat!”

It’s only when she’s talking about her breakdown that Knightley’s tongue-in-cheek tone falters. In 2019, she described having been at the centre of a victim-blaming culture in which she was “stalked by men” and told “You wanted this.” It is not an experience she draws on; she prefers to keep it in a box.

“The adult me is very aware that people can go through very difficult periods in their life, and they do not come out of it with a very successful career and a very healthy bank balance,” she explains. “I feel incredibly fortunate. Did it come with a big side of a load of other stuff to deal with? 100 per cent, it did. I don’t think the way that photographers or journalists behaved to young women in the entertainment industry in that period of time was in any way acceptable, or in any way OK. And as the adult speaking, 100 per cent it was an atrocious way for that section of the media to behave to young women.” Does it still affect her? “Yeah,” she says straight away. “Um, it does. Yeah.”

Generally, Knightley has no ongoing relationship with the films she makes: she’ll see them once, then become detached from the finished project. She certainly hasn’t come across the thousands of Love Actually memes circulating online (most of her saying “They’re all of me”, laid over pictures of people’s cats). But with longevity, she has accrued a justified esteem and affection among the public. “I think being a 40-year-old woman, people have a different response to you than when you’re 18. That’s just the way the world is,” she says. “When you’re 18, you haven’t got much work, you’re all image. When you have a career that’s 25 years long, and you’ve got enough stuff to be like, ‘Well, that’s a body of work; some worked, some didn’t’ – people can look, and go, ‘That’s a career.’”

A whole career, involving many guises. As Knightley shrugs on a brightly embroidered denim jacket and slings a tote bag over her shoulder, heading to a costume fitting for the second season of Black Doves, she slips into her latest one. Scribbling a message in her book for my daughter, she writes: “With love from the lady who drew the cat.”

‘I Love You Just the Same’ is published by Simon & Schuster