It was May 4, 1975. The Japanese Women’s Everest Expedition team had been living at a high altitude for six weeks, and were less than a week away from their scheduled bid for the summit of Mount Everest. Exhausted, having established camp five at just below 8,000m on the south side of the mountain, Junko Tabei and the team descended to camp two at 6,300m to rest.

Then – avalanche!

In the early hours, tons of ice and snow engulfed the camp, burying several of the teammates. Crushed by the snow and ice, Tabei was unable to move. It took the strength of four Sherpas, the elite Nepali climbing guides assisting the expedition, to pull her out. Suffering severe bruising, Tabei argued that she did not need to be returned to base camp to recover, and would remain at camp two.

“There was no way I was leaving the mountain,” she recalled in her memoir.

It had taken five years for this group – the first all-women team – to get to Everest. The pressure on them to succeed was immense, given the limited number of annual international permits to climb Mount Everest issued by the Nepalese government. If they gave up, they might have to wait several years to make another attempt.

Meanwhile, on the Tibetan side of the mountain, Tabei’s team had competition. A 200-strong Chinese team was also working to place a woman on the summit at the same time.

From the late 1950s, Tibetan women were recruited to participate in state-sponsored Chinese mountaineering expeditions. In 1958, Pan Duo had been selected to participate in the successful Chinese 1960 Everest expedition – but was ordered to remain below 6,400 metres because above that height was “a man’s world”. Nonetheless, Pan Duo – referred to as “Mrs Phanthog” in some older accounts – was celebrated in her country and elected deputy captain of the 1975 Chinese Everest Expedition.

Unfortunately, the Chinese team suffered a climbing accident resulting in the death of a team member. They retreated to recover – only to be ordered by the Chinese government to “climb ahead of the Japanese women”.

They were too late. On May 16 1975, the all-women Japanese expedition worked together to place Tabei on the summit of Everest. Two team members – Tabei and Yuriko Watanabe – had been nominated to make the summit attempt. However, other teammates were suffering from altitude sickness, so Watanabe was assigned to help return them to camp two.

The ascent Tabei was making was arduous. Given her injuries, it took great tenacity to muster the strength to continue. But finally, she took her last steps to the summit, becoming the first woman and 40th person, according to the latest official record, to summit the peak. She was part of only the tenth successful Everest expedition, later recalling: “I felt pure joy as my thoughts registered: ‘Here is the summit. I don’t have to climb any more.’”

Eleven days later, the Chinese team returned to the high slopes to make another attempt. Using minimal oxygen, Pan Duo was also successful, becoming the second woman to summit Everest – and the first to climb the harder northern side of the mountain.

Prior to these two successful expeditions, only 38 people had summited Everest – all of them men. News of Tabei’s feat travelled fast across Asia, leading to national celebrations in Japan, Nepal and India. But it made little impact in the west.

In my own career as both a mountaineer and researcher of adventure tourism, I had been struck by how few women I encountered on the mountainside. I wanted to understand why this might be, and what women had achieved. It was through this research that I discovered Tabei’s story.

I was astonished both by her achievements – she is also the first woman to complete the “Seven Summits”, climbing the highest peaks on every continent – and by how few prominent mountaineering organisations and mountaineers appeared to know about her.

Tabei’s bravery helped her lead record-setting all-women expeditions and overcome the mountain of sexism in this male-dominated space. Yet very few organisations, even in Japan, have thought to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first ascent of Everest by a woman.

Historically, men have dominated the public record in mountaineering. In the last few years, the 70th anniversary of the first summit of Everest in 1953 by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay has been marked, along with the centenary of the unsuccessful and fatal attempt by George Mallory and Andrew Irvine in 1924.

During that period, women were excluded from many mountaineering clubs. When they did join, they often faced prejudice, were discouraged and sometimes not permitted to publish records of their adventures. In 1975, women were finally admitted to the Alpine Club, the first and one of the most prestigious climbing institutions.

At a time when Japanese women were expected to remain at home, many members of the Japanese Women’s Everest Expedition, including Tabei, were working, with two of them also raising children. Tabei’s daughter, Noriko, was three at the time of her Everest summit. Tabei later revealed that the expedition encountered significant resistance:

Most of the men in the alpine community opposed our plan, claiming it would be impossible for a women-only expedition to reach Everest.

As a married woman and the assistant expedition leader, Tabei felt torn between motherhood and mountaineering, explaining: “Although I would never forfeit Everest, I felt pulled in the two directions of mountains and motherhood.”

Facing unsympathetic attitudes from team members when childcare conflicts arose, Tabei realised she needed to put in extra effort to prove herself as a leader.

Years before the Everest expedition, Tabei and other Japanese women were already logging major climbing achievements across the globe. These included the first ascent of the north face of the Matterhorn by an all-women’s team in 1967, and the first all-women’s Japanese expedition to the Himalayas in 1970 to climb Annapurna III. Tabei was both the first woman and Japanese person to ascend the peak.

This set the scene for the Japanese Women’s Everest Expedition. To locate and train suitable candidates for the expedition, Tabei helped establish the Joshi-Tohan Japanese Ladies Climbing Club, founded on the slogan: “Let’s go on an overseas expedition by ourselves.”

Tabei’s contribution to women’s high-altitude mountaineering was astounding. To reach Everest, she defied mid-20th-century social norms that tied Japanese women to domestic roles, later musing: “I tried to picture myself as a traditional Japanese wife who followed her husband. The idea never sat well with me.”

Throughout her career, Tabei contributed significantly to the emerging culture of women’s climbing and mountaineering expeditions. She felt strongly that climbing with other women was more rewarding because there was greater physical equality.

In 1992, she became the first woman to ascend the highest peaks on all seven continents. Using her celebrity, Tabei was also an activist for environmental change in high-altitude regions, having grown appalled by the degradation of fragile mountain glaciers that was being caused by the mountaineering industry.

With her friend and Everest teammate Setsuko Kitamura, Tabei established the first Mount Everest conference in 1995, inviting all 32 women who had by then successfully climbed Everest (not all attended). Under her leadership, this transnational exchange created a space to celebrate women’s mountaineering achievements.

Soon after her Everest achievement, Tabei had been a symbol of social progress and women’s emancipation at the UN International Women’s Year world conference. Yet her status as one of the greatest high-altitude mountaineers has since faded from the public eye. This has much to do with the stories we tell about man – and it’s almost always a man – vs. nature.

Hillary’s much-lauded autobiography, High Adventure (1955), was published two years after his first successful ascent of Everest. In contrast, it was 42 years after her ascent before Tabei’s memoir, Honouring High Places, was published and translated.

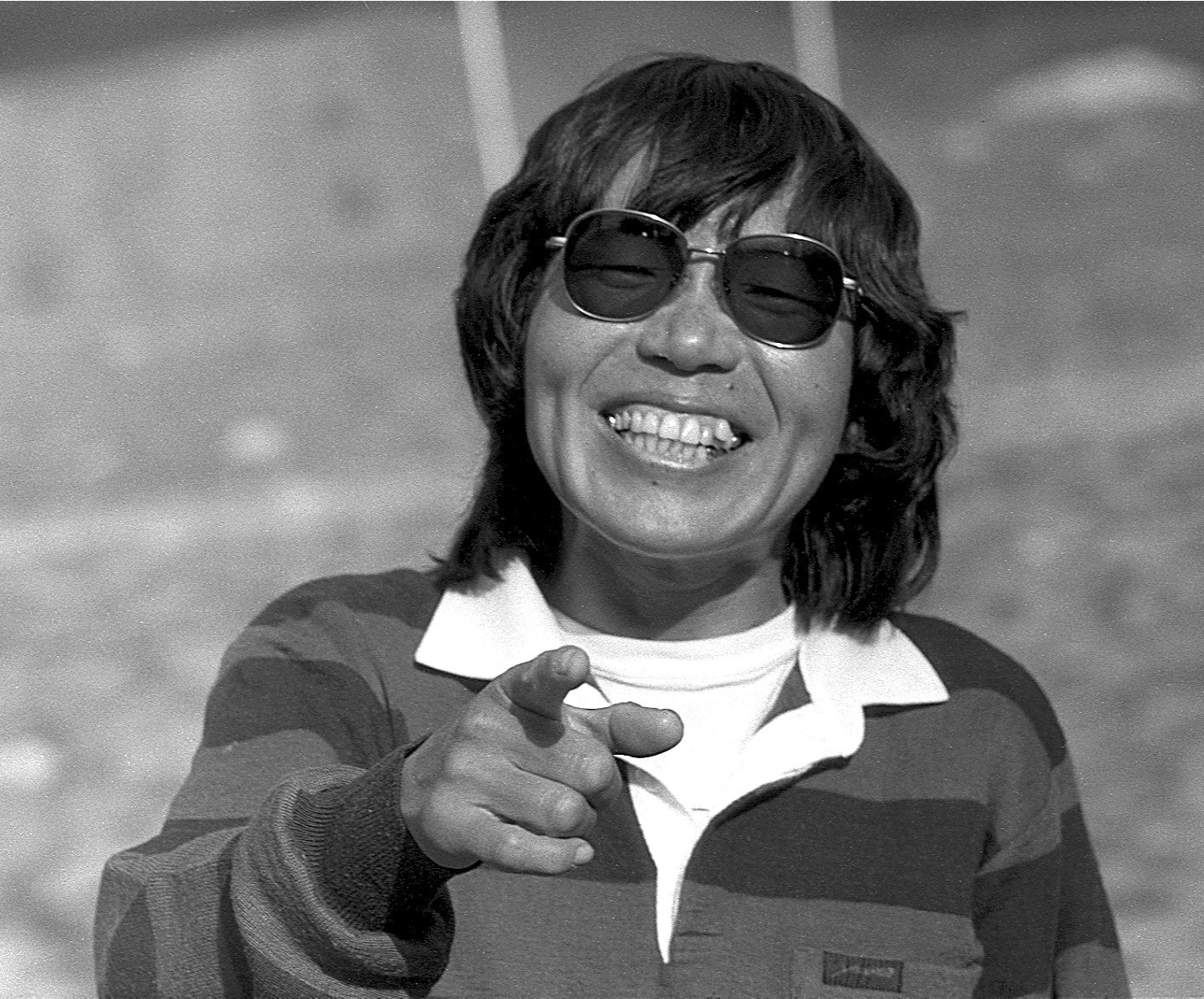

The way Japanese women’s experiences were represented in the media did not, in Tabei’s view, represent the reality of women’s experiences. She was particularly perplexed by the inability of the press to see beyond her gender. She was repeatedly asked how it felt “as a woman” to climb at high altitudes.

Portrayals of Tabei focused on her stature as a small Japanese woman. This only reinforced the perception that women like her did not fit the norm of the heroic white, male mountaineer. She reflected:

When people meet me for the first time, they are surprised by my size. They expect me to be bigger than I am, more strapping, robust, like a wrestler … I was always puzzled by this, by people’s obsession with the physical appearance of a mountaineer.

To counter this narrative, Tabei brought a new approach to writing about Japanese women mountaineers’ achievements – challenging the tendency of traditional Japanese expedition publications to gloss over the harsh realities of expedition life.

Critical of the flowery and vain writing style of these reports, Tabei’s frank accounts reported on the “unkinder side of human behaviour”. Making tough choices was particularly difficult for women, she wrote, because of their social conditioning to be a “good person”:

It was unusual enough to be a female climber in that era of yesteryear, let alone to make a stand in front of your friends that would possibly upset them.

Transcending these social norms had a personal impact. Tabei lamented that, although “I remained strong-willed about Everest, tears of doubt fell down my cheeks at night”.

Her honesty was criticised by some in the established mountaineering community in Japan, particularly in her published account, Annapurna: Women’s Battle, which expressed the raw emotions and feelings experienced on their 1970 expedition. Tabei shared “the feelings of the team members when things failed to go in the direction they had envisioned … We put our honest experiences on paper”.

Reflecting on how she had to overcome social norms to lead the expedition – “In my day, we were strictly advised that being different was abnormal” – Tabei concluded that: “A person must be able to voice her opinion without worrying about criticism.”

A problem of representation

Ever since the late 1850s, women have made a significant yet often-hidden contribution to mountaineering. It retains a powerful legacy of male-dominated clubs and governing institutions founded on masculine norms such as risk-taking. This has often cast mountaineering achievements in a way that privileges men.

Clubs established traditions based on the first ascents of mountains – very few of which were made by women. Their absence from leading mountaineering clubs and lack of representation in published club journals meant their achievements were often attributed to male companions.

In 1872, the American climber Meta Brevoort felt it best, due to social prejudice, to publish her extraordinary first ascents in the European Alps under the name of her nephew, William A.B. Coolidge. Mountaineer and author David Mazel notes that Brevoort’s account was “carefully written to conceal the author’s sex”.

Mountain exploration and climbing have traditionally been framed as heroic endeavours dominated by men. Figures such as Hillary, Mallory and Reinhold Messner are celebrated for their bravery, strength and leadership — traits associated with masculinity.

Early mountaineering narratives often emphasised physical endurance, dominance over nature, and the ability to withstand extreme conditions – reinforcing ideas of masculine heroism. Mountains as towering, imposing and seemingly unconquerable landscapes have been metaphorically linked to power and challenge.

Traditions that have been passed down through generations – from ascent styles to route names – have also been synonymous with masculinity. In the words of mountaineering historian Walt Unsworth, climbing Everest “is the story of Man’s attempts to climb a very special mountain”.

This has had real-world consequences for mountaineering. Today, only 6 per cent of British mountain guides are women, while globally, less than 2% of those registered to the International Federation of Mountain Guide Association (IFMGA) are women. If you don’t see your face reflected, it becomes a daunting prospect to imagine yourself in mountaineering – whether as a mountain guide, or an amateur mountaineer like me.

By 2024, women represented 13 per cent of all Everest summiteers since 1953, yet their stories are seldom told. White, male, able-bodied and middle-class voices dominate representations in published records and popular portrayals of adventure on the world’s highest mountain.

As anthropologist Sherry B. Ortner attests, this is not surprising given mountaineering’s history as a western imperialist and colonising project that aimed to conquer nations and nature, built upon all-male institutions. Yet men and women have the same statistical odds of making a successful summit or dying on Everest.

Julie Rak, in her book False Summit, shows how some accounts can treat women’s achievements with ambivalence, and at worst question their authenticity. It has even been suggested that Tabei was effectively dragged up the mountain by her friend, the male Sherpa Ang Tsering.

Having suffered significant trauma following the avalanche that nearly wiped out their 1975 expedition, Tabei showed enormous courage and resilience to summit Everest just a few days later. She describes the ascent as difficult – and yes, accepted help from Ang Tsering – but this was her achievement, not a “stunt” to be denied by those who were not even present.

Diversity on the mountain

Since Tabei’s Everest summit, mountaineering has undergone changes as a sport, shifting from an elite, exploratory pursuit to a commercialised industry where wealthy clients can hire companies to reach summits with professional support.

From the late 1980s, high-altitude mountaineering became a valuable tourism commodity. Seizing the opportunity to boost tourism, the Nepalese government began to issue more permits, fuelling the growth of commercial companies offering clients the opportunity to be guided up 8,000-metre summits. In 2023, Nepal welcomed over 150,000 high-altitude trekking and mountaineering visitors, with 47 teams attempting to climb Everest.

Yet despite the popularity and commercialisation of the sport, mountaineering remains stubbornly resistant to diversity.

Scholar Jennifer Hargreaves argues that women have been excluded from being represented as the “sporting hero”. What constitutes our cultural identity, meaning and values almost exclusively solidifies heroic masculinity in most forms of sport, including mountaineering.

And much of this is due to the stories that are – not – told.

Delphine Moraldo’s research found that of the mountaineering autobiographies published in Britain and Europe from the late 1830s to 2013, only 6 per cent were written by women.

Historically, literary representations of women mountaineers have often been met with ambivalence, their achievements portrayed as lesser. Women are stereotyped as weaker, bound to domesticity and lacking the hardiness required to be a “good mountaineer”.

These perceptions, coupled with a lack of representation, have reduced women’s opportunities to secure funding for expeditions, or to access female-specific clothing and equipment. Tabei and her team had to make their own expedition clothing because women’s sizes did not exist, a problem that remains today. When raising sponsorship for Everest, she was told: “Raise your children and keep your family tight, rather than do something like this.”

But while there is still a mountain to climb when it comes to attaining equality in adventure sports, there is a growing body of research and media celebrating women’s achievements – from campaigns such as Sport England’s This Girl Can to films charting the lives of some women mountaineers.

Junko Tabei and Pan Duo’s names may never be as well known as Edmund Hillary’s. But they are just two of many women whose achievements reach far beyond the peaks. I’ve written about many of them in my research.

Polish mountaineer Wanda Rutkiewicz was the third woman and first from Europe to summit Everest. When asked in 1979 by high-altitude record holder Maurice Herzog why she had climbed Everest, Rutkiewicz responded that she did it for “women’s liberation”. By the late 1980s, such activism was harnessed by large sponsors such as Tata Steel, who recruited Indian mountaineer Bachendri Pal, the fifth woman to summit Everest, to lead a women’s adventure programme.

Corporate sponsorship has, however, eluded many leading women mountaineers. Despite all her outstanding achievements – including holding a world-record ten Everest summits by a woman – Lhakpa Sherpa struggled for years to achieve recognition and the status of her male contemporaries. In 2019, writer Megan Mayhew Bergman asked why she didn’t have sponsors.

More recently, however, Lhakpa Sherpa’s mountaineering career was documented in the 2023 Netflix documentary Mountain Queen, which raised her profile and has led to new sponsorship opportunities.

There is also work being done to change the exclusion of women from mountaineering. In Nepal and around the world, charitable organisations have been initiated by women mountaineers to help their fellow women climbers, including Empowering Women Nepal and 3Sisters Adventure Trekking.

My research has shown how women and mountaineers from other marginalised backgrounds can use their successes to become role models for and drivers of social change.

Tabei, for example, was appalled at the degradation mountaineering had caused to Mount Everest, and spoke out about the need for responsible mountaineering and conservation. She led cleanup expeditions and researched the environmental impact of tourism and climate change on both mountain ecosystems and local communities.

Tabei’s efforts helped bring global attention to the need for conservation in high-altitude environments, inspiring climbers to take a more responsible approach to their expeditions.

In research about Asian women’s contribution to climbing Everest, I examined how the struggle for women’s emancipation, empowerment and recognition is a phenomenon that is shared globally. A new generation of Asian women mountaineers such as Dawa Yangzum Sherpa, the first woman to achieve IFMGA status, and Shailee Basnet are defying gender norms and achieving status as internationally recognised mountaineers and mountaineering guides.

Basnet became one of 10 women to scale Everest in 2008 as part of Sagarmatha Expedition, which was established to draw attention to climate change and gender equality, and to reclaim the Nepali name for the mountain: Sagarmatha. The expedition brought together ten women from six different religious, caste and ethnic backgrounds. All ten reached the summit, making it the most successful women’s expedition to date.

Following this, in 2014 Basnet led the formation of the first all-women Seven Summits project to climb the highest peak on every continent. Importantly, she harnessed the team’s newfound profile to undertake a large-scale social justice programme, visiting hundreds of schools, leading hikes and giving talks across the Kathmandu Valley. Their mission was to improve educational awareness concerning opportunities for women and girls, and also to protect the environment.

‘A life we would never regret’

Since the mid-1950s, a hidden sisterhood has forged a route for women to access high-altitude mountaineering. Their impact has reached far beyond the expeditions they led.

Women have used their status as mountaineers to empower and support other women to achieve social, political and environmental justice, and raise awareness about poverty, sex trafficking, religious and ethnic marginalisation, environmental degradation and the impact of mass tourism.

Junko Tabei was a pioneer whose tenacity helped a whole generation of women in mountaineering. By not recognising their achievements, we deny an important part of our cultural heritage – and miss the opportunity to learn and share the inspirational work that women continue to undertake.

Tabei’s memoir is not simply a remarkable mountaineering account, it is, in the words of Julie Rak, a feminist text that challenges what society has always thought it means to be heroic, brave and adventurous.

Tabei died in 2016 at the age of 77. On the 50th anniversary of one of her many achievements, it’s fitting to end with these words from her memoir: “My approach was one of not worrying about the loss of a job or missing out on a promotion. I felt it was important to live a life we would never regret.”

Jenny Hall is an Associate Professor in Tourism and Events at York St John University

This article was originally published by The Conversation and is republished under a Creative Commons licence