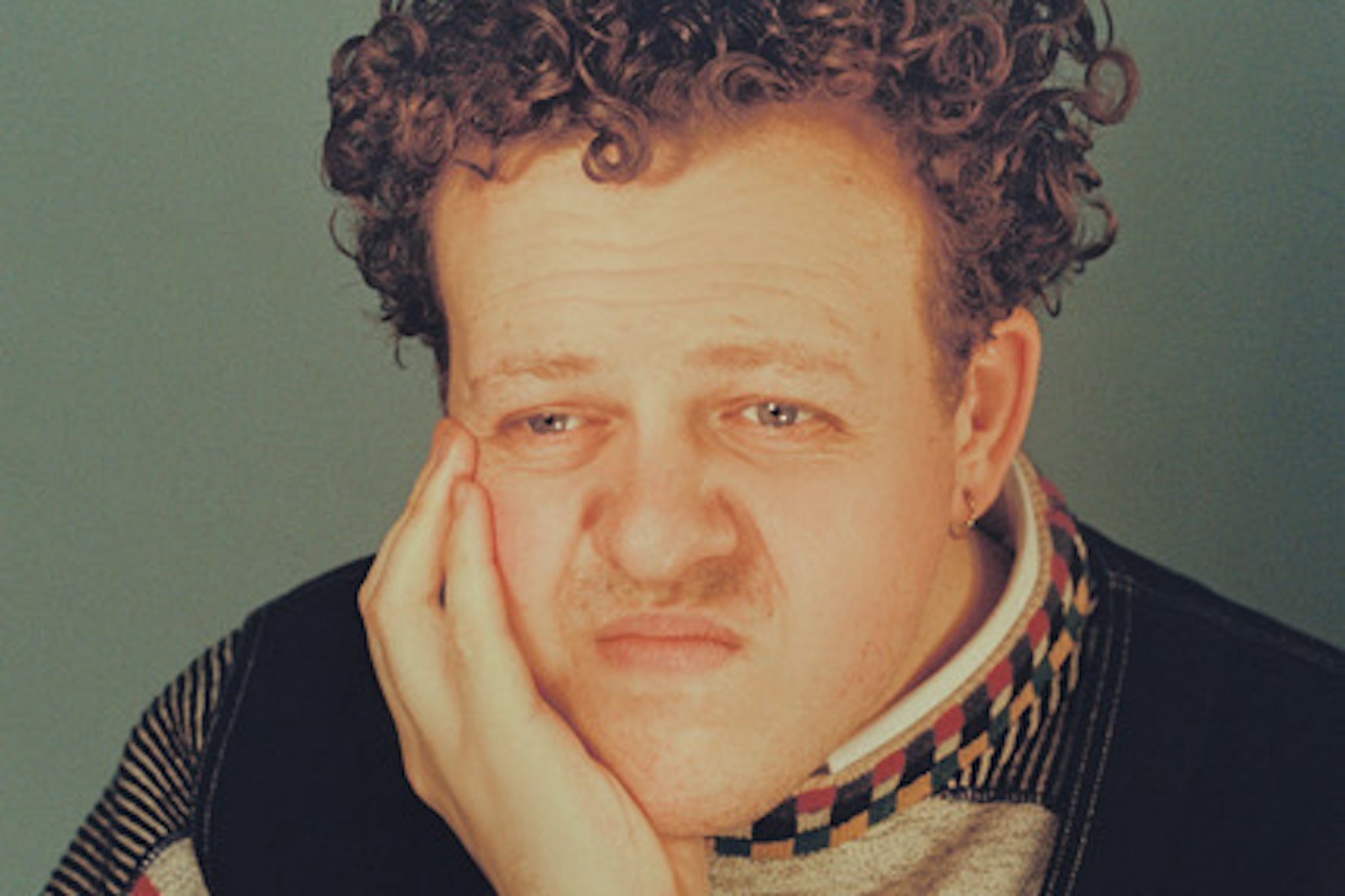

Jack Rooke has just cycled furiously, in a trenchcoat, to avoid being late for an interview – this interview – to discuss the acclaimed final season of his Channel 4 sitcom, Big Boys. Who would have begrudged him being a little late? After all, this is one of the busiest and happiest weeks of his life. Isn’t it?

“The answer is no,” he tells me, cradling an Americano while his PR handler scrolls idly on his phone, just out of earshot. “I’ve often felt, this week, a little bit like slamming my head against a wall. A lot of this week has been like: ‘I couldn’t have worked harder for a show that I’m not sure anybody knows has even come out.’”

This disarming candour will be less surprising to those familiar with Big Boys (spoiler alert: this article contains details of the final episode of Big Boys season three). After all, the show has always peered, with infectious affection, into the unexpected recesses of life. Set at the fictional Brent University, it followed a haphazard group of friends through the tribulations of student life. At the heart is Dylan Llewellyn’s Jack, a surrogate for Rooke, coming to terms with his sexuality, and his roommate Danny (Jon Pointing), a seemingly confident “lad” who is struggling with repressed mental health issues. It was an odd-couple dynamic for the 21st century. What began life as a pilot for the BBC – and was developed by E4 as a “really bad Inbetweeners copycat with poonani jokes” – ended up as one of the most celebrated and affecting shows on TV.

But for Rooke, who has graduated from precocious newcomer to coveted showrunner, the fawning 5-star reviews (including in these august pages) mean far less than the sense that people, out there in the real world, are actually watching. “It only takes like three people, unconnected to the show, to say they didn’t know it was out before you’re like, ‘what was the f***ing point of working my arse off for two years?’” He looks apologetic after this last judgement. “I’m probably being a bit miserable about it,” he confesses, “because that’s my current feeling at 8am in the morning.” (It’s almost 10am, but one must make allowances for the writerly temperament).

Big Boys’ final season – its third – has rounded out a story that began a decade ago. Despite living between Watford and Rickmansworth (a deeply unsexy corridor of this island nation), Rooke blagged his way into student accommodation at the University of Westminster’s Harrow campus (the proto-Brent Uni). It was a move that – in ways both linear and not – would eventually lead to Big Boys. After completing a journalism degree, he spent time as a teaching assistant and worked as a runner for live events, before winding up at Radio 1, manning the phones for their call-in service, The Surgery. At the BBC, he began to flirt with documentary filmmaking.

But the real source of professional inspiration was found away from New Broadcasting House. “I’d started doing quite naff comedy poems above pubs,” he recalls. “I think almost as an exercise in trying to gain confidence.” This hustle is immortalised in the final season of Big Boys, where the on-screen Jack bombs with a performance poem about Madeleine McCann. “I think that’s the scene my friends have been most triggered by. None of the suicide s***. It’s me trying to be a poet.”

The “suicide s***” to which Rooke alludes, is a spectre that has hung over Big Boys from the off and was at the heart of the material Rooke developed for the Edinburgh Fringe. The character of Danny is a hybrid of friends that Rooke made at university and in his early twenties, one of whom died by suicide. “I would say the character of Danny is based on three or four of my friends,” he says. “Three are still here and one is not. And it’s a direct letter to the one who’s not, in a really earnest, emotional, autobiographical way.” Indeed, the show has always been addressed by Rooke – who serves as the narrator – to you. “You” being Danny, “you” being lost loved ones.

The final two episodes of Big Boys are the culmination, comedically and emotionally, of this story Rooke has been working on for a decade. A final sequence, in which Rooke (the man, not the character) enters the narrative, to speak to Danny on a bench overlooking the sea in Margate, is a moment that will stand alongside those rare instances when comedy transcends its genre constraints. Radar O’Reilly interrupting the 4077th M*A*S*H to announce that Henry Blake’s plane has been shot down, BoJack calling to Sarah Lynn at the planetarium, Fleabag, alone, at the bus stop. Add to that, now, a rumination on meal deal inflation.

“Jack always had that scene in his head from day one,” Big Boys’s director Jim Archer tells me via email. “What was tricky to get right was the balance of truth and story,” he says. “That’s the genius of Jack’s writing in that scene. To balance truth and story and create a finale that satisfies both endings is an amazing tightrope to walk.” For the scene – one of the televisual moments of the year already – Rooke and Archer changed the aspect ratio to create a visual separation from the show’s widescreen, sitcom aesthetic and allowed the conversation to run for over seven minutes. The camera lingers plaintively on the Kentish coast, and Antony Gormley’s half-submerged statue, “Another Time”, stares back at Jack and Danny from the sunlit waves. “The day we shot it was lovely. Beautiful weather. I know it’s a sad scene, but we had a lovely day!”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

“I felt quite protective of Jack in those moments doing those scenes,” Pointing tells me. “I tried, always, to be really calm and be just sort of there and make him feel comfortable.” Theirs is a friendship that goes back to their days as writers and performers at the Fringe, long before Big Boys was a reality. It was there, back in the early 2010s, that Rooke knew he’d found his Danny. “We were in a kebab shop at 3am,” Rooke recalls. “And I just whispered in his ear – in this Danny Dyer comedy voice – ‘I dare you to get a pizza.’ And we laughed so much. In that moment, I was like: ’You’re Danny.’”

“Obviously it really made me laugh because it was silly,” Pointing recalls. “But in my head, I was transported back to being 17. We’ve gone out, we’ve got drunk, we’ve ended up at a kebab shop, and someone’s trying to inject some fun into the evening.”

This reverence for life’s beautiful banalities runs through Rooke’s work. He might lament the fact that “there’s a ceiling to any project that talks about Gamu from X Factor” but there are few shows that better understand quotidian profundities, like the rise of sweet chilli or the angelic aura of Alison Hammond. In the show’s final episode, Pointing’s Danny and Jules – an over-eager student counsellor played by comedy stalwart Katy Wix – find themselves on a “cheeky 37-minute detour” to Fleet Services. It is the backdrop, of course, for another emotional rug pull.

“There’s this sense of responsibility,” Wix tells me. “It’s got to be right, this big ending, it’s got to be the right tone.” Wix has been part of the ensemble since its early days as a half-baked pilot, and has herself written a book, Delicacy, that deals, in wryly comic fashion, with the subject of grief. “Because it’s a subject that I have a personal connection with,” she says. “Everyone got upset at different times, for different reasons. You have to be boundaried about it but also let the subject in enough that you’re moved in the moment.”

Viewers will make their own minds up about the show’s finale, but Rooke has known how the saga would finish since first pitching it. The material formed the foundations of his Edinburgh shows Good Grief and Happy Hour. That festival has proved fertile ground, in recent years, for television adaptations of darkly comic British tales like Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag, which was first performed there in 2013, and Richard Gadd’s Baby Reindeer, which was adapted last year by Netflix and became a global smash hit.

“Richard [Gadd] dramaturged my Edinburgh shows,” Rooke explained. “He kind of explained the Fringe to me.” And Rooke was with Gadd in a pub in Kentish Town when, some years later, he heard the news that his friend (one of Danny’s forebears) had died. “It’s weird. It’s the 10-year anniversary of my friend’s passing in like two weeks. It’s the week after the show comes out, which feels quite odd but also quite a nice way of wrapping up.”

Which brings us back to where we started, with the inevitable depression of being an artist putting your work out into an uncaring world. “You work your arse off to almost try and impress yourself,” he admits. “I’ve done that and I’m really proud of it. But I’m really excited to write something that’s not autobiographical in any way.” That is the next challenge. He demurs when I throw ideas at him. Will he follow Gadd onto Netflix? No comment. Is he working from some existing IP? Hmm. Is he going to be the next James Bond? Slight eyebrow twitch.

“Bloody hell, mate,” Pointing exclaims, in true Danny fashion, when I ask him to assess how Rooke has developed as a writer. “There’s a part of Jack that’s this supernova – very intelligent, very engaged, with this massive library to draw from. I watched him on this job, over the years, learn a different part of his craft. He’s always been a good writer, now he’s learnt how to make a TV show.”

“I think he’ll be fine now,” is Wix’s judgment. “He’s proved himself enough to have the choice to do things he wants to do.” For Archer, meanwhile, Big Boys is a hard act to follow. “Jack is such an amazing writer that it has now really raised the standard by how I judge a script. I’ve become very picky!”

At just 31, staring at the dregs of cold coffee, Rooke might have shaken off the “wunderkind” tag but there is still much to look ahead to. “In my early twenties, performance artists and comedians in their thirties and forties were telling me to bare my soul,” he recounts, with the gentle cynicism of a world-weary raconteur. “And now I f***ing regret it. I did it really carelessly.”

And yet “careless” isn’t really the word you’d use for Big Boys, a show crafted with such care, such intentionality. Start to finish, it has been Rooke’s vision. “I was really lucky,” he admits, finally. “Sometimes I speak to friends of mine who slogged their twenties trying to have any kind of creative job, but I came out of uni, had maybe 18 months of working odd jobs, and then it just landed.”

Big Boys landed, and now Rooke – without recourse to cheap bird puns – is about to take off.

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email [email protected], or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

If you are based in the USA, and you or someone you know needs mental health assistance right now, call the National Suicide Prevention Helpline on 1-800-273-TALK (8255). This is a free, confidential crisis hotline that is available to everyone 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

If you are in another country, you can go to www.befrienders.org to find a helpline near you.