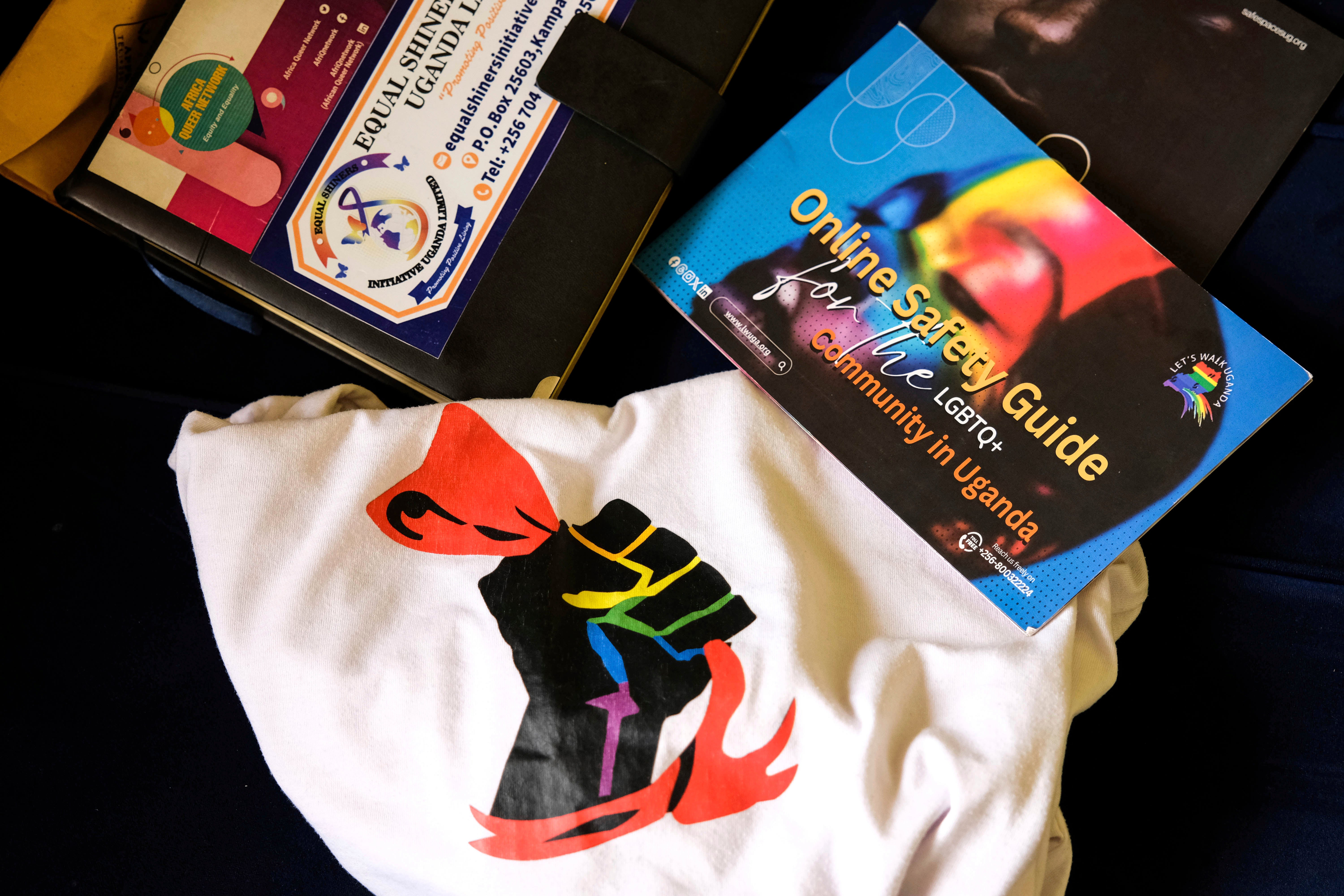

One of Uganda’s most prominent LGBT+ activists says he has “lost hope” his country’s extreme anti-homosexuality law being repealed – with Donald Trump’s decision to slash US foreign aid funding removing one of the key pressure point on the government.

Steven Kabuye was brutally attacked in 2024, in the wake of the law – which punishes consensual same-sex relationships with penalties up to life in prison – being passed the previous year. He had been receiving regular death threats when, on his way to work in January 2024, he was stabbed twice by two unknown men and left for dead. After the attack he was given asylum in Canada. “I almost lost my life that day,” he explains. “[It] almost cost me my life and I’ll continue doing this work until the day the gods decide this is my end”.

Aid cuts and sanctions against Uganda introduced by Democratic presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden, as well as pressure from the World Bank, are thought to have played a role in overturning some limited aspects of the legislation. “But with the Trump government coming into power in the US, everything went back”, Kabuye says, and the milestones they had achieved, “all withered away”.

Kabuye fears it will be impossible to convince President Yoweri Museveni, Uganda’s leader of almost 40 years, to “remove some draconian laws without leverage”.

“How are you going to leverage him? By giving him aid,” he says. “Without aid you have nothing on him”.

Though the majority of the harsh law remains in force, a general obligation to report suspected “acts of homosexuality” to the police has been revoked, thanks to US pressure. The provision had led to LGBT+ people being denied or too afraid to seek healthcare.

“Before all the sanctions that came from the US under the Biden administration,” Kabuye explains, the Ministry of Health in Uganda used to run workshops for medical workers telling them, “how to report anyone who is suspected of being transgender”.

Then, financial pressure from the US and beyond, “at least pushed the Ugandan government,” Kabuye explains, to remove some articles of the law that were, “very very severe and are very harmful” . It also pushed the health ministry to make sure LGBT+ people could access healthcare including HIV medication in specialist drop-in centres funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), he adds.

Using aid as leverage has been controversial at times. When the British government threatened to cut aid to countries that persecuted gay people, a group of more than 50 African social justice organisations signed an open letter expressing concerns about, “the use of aid conditionality” as an incentive to uphold LGBT+ rights , because of the “real risk of a serious backlash” against the very people they are aiming to protect. “Donor sanctions are by their nature coercive and reinforce the disproportionate power dynamics between donor countries and recipients,” the letter added.

Two years on from halting new lending to Uganda saying its anti-gay law violated the bank’s values, the World Bank reversed its decision at the start of June, saying it now believes measures put in place to prevent harm from the law were “satisfactory”.

‘They cannot afford these medications’

On the ground in Uganda, US aid cuts have led to the closure of many such health centres, forcing people back into public hospitals where they may be discriminated against. Organisations supporting LGBT+ people living with HIV told The Independent they had also seen a rise in verbal attacks and denials of care in hospitals after Trump not only withdrew funding for those groups, but also mounted targeted attacks particularly on trans people in the US.

A State Department spokesperson said that while the US had reprioritised foreign spending to, “advance US prosperity, security and safety,” a review remained ongoing and in the meantime the US continued to fund “significant lifesaving and humanitarian assistance” in Uganda.

The United States has long stood for the protection of human rights and equal treatment under the law, the spokesperson added, and all authorities to challenge human rights violations and corrupt actors continued to be available to the US government. US sanctions against some Ugandan officials for rights violations remain in place.

Since US aid-linked closures of HIV clinics in Uganda – as well as the loss of staff who used to deliver medicines to some patients’ homes – Kabuye says people are now “running back into the dark corners wondering when all this will stop”.

Kabuye is now supporting three of his friends financially to help them to buy life-saving anti-retroviral medication which they were previously able to get for free.

“These are people that actually cannot work due to the limitations that are put in place by the Anti-Homosexuality Act 2023. They cannot afford these medications. They cannot afford transportation to go to the main hospitals.”

Beyond the fear and distress caused, cutting access to HIV prevention and treatment will lead to “loss of lives and a lot of them,” Kabuye warns.

The Ugandan government has denied this, saying: “As a government, we uphold a non-discriminatory policy in service delivery, ensuring equal access to healthcare for all”.

A spokesperson added: “The legislation was passed and signed into law by the Ugandan government to safeguard the interests of Ugandans and future generations. Importantly, the law still upholds the right to seek health services without discrimination. All health facilities continue to provide care, including free services.”

Watching the impact of US cuts play out from afar in his new home in Vancouver has been “traumatic”, Kabuye says. “I feel like I have to do something, but I cannot. It makes me powerless, but then I have my voice. I can speak up. I can inform the world what is happening out there”.

The experience of his attack – which he believes happened as a result of his activism – hasn’t left him. “It will always come back in my memories when I sleep. When I watch TV, if I see a certain story that connects with my experience. If I see blood. When I look at my scars.

“I’ll walk with it for the rest of my life. I just have to accept that it happened, and I survived”.

This article was produced as part of The Independent’s Rethinking Global Aid project