This week the eclectic membership of the International Olympic Committee has travelled from all corners of the globe to Ancient Olympia, the spiritual home of the Games, to vote in secret for their next president. The 109 members include a Mongolian banker, a former Cape Verdean school teacher, a Fijian doctor, a Bhutanese prince and the Grand Duke of Luxembourg, as well as HRH Princess Anne, and they must decide who succeeds Thomas Bach as the most powerful sporting figure in the world.

The IOC president holds enormous sway not just in sport but in global politics – the first person to call Bach and congratulate him on winning the 2013 election was Vladimir Putin. The next president, who will win an eight-year term with a possible four-year renewal, will lead the IOC into a challenging world, facing down the climate crisis, deeply divisive issues of gender, the advancement of AI and a rapidly changing entertainment-scape, and all with Los Angeles ‘28 on the horizon which President Trump will seek to hijack for his own ends.

And yet the election itself is a mysterious, clandestine operation: no open debates, no criticism of rival candidates, no public endorsements by members. Candidates gave 15-minute presentations at the IOC’s headquarters in Switzerland last month without follow-up questions. There was no TV broadcast and recordings were strictly prohibited.

In the background over the past few months, seven hopeful candidates have been privately lobbying members for their votes via face-to-face meetings and personal calls, trying to build a support base for their campaign. It is a tangled web of allegiances that The Independent has spent weeks attempting to unpick, speaking to sources including several IOC members with voting powers to understand the state of play before Thursday’s once-in-a-generation election.

As one member explained of the discussions that go on behind closed doors: “Everybody tells you who they’re voting for, and no one tells you the truth.”

Perhaps the most high-profile and contentious candidate is Lord Coe, Britain’s double gold medallist who now heads up World Athletics, the Olympics’ king sport. Coe is a highly respected and influential player with a proven track record of winning major campaigns after masterminding London’s victory over Paris to host the 2012 Games. But in the corridors of the IOC’s headquarters he is a divisive figure. Coe has been openly critical on a range of issues and his outspoken approach has often ruffled feathers, so much so that he is “loathed” by some senior IOC figures, according to one source.

A disputed incident was Coe’s announcement last year that gold medalists in track and field events at the Paris 2024 Olympics would receive a $50,000 prize. The move caught the IOC off guard and left some figures furious that Coe was “playing solo”, even if he was entitled to do so. It is said that Coe has struck a notably open and receptive tone in discussions with members over recent weeks, as he bids to make up any lost ground. Coe has plenty of backers but he may need to win over some detractors if he is to claim the presidency.

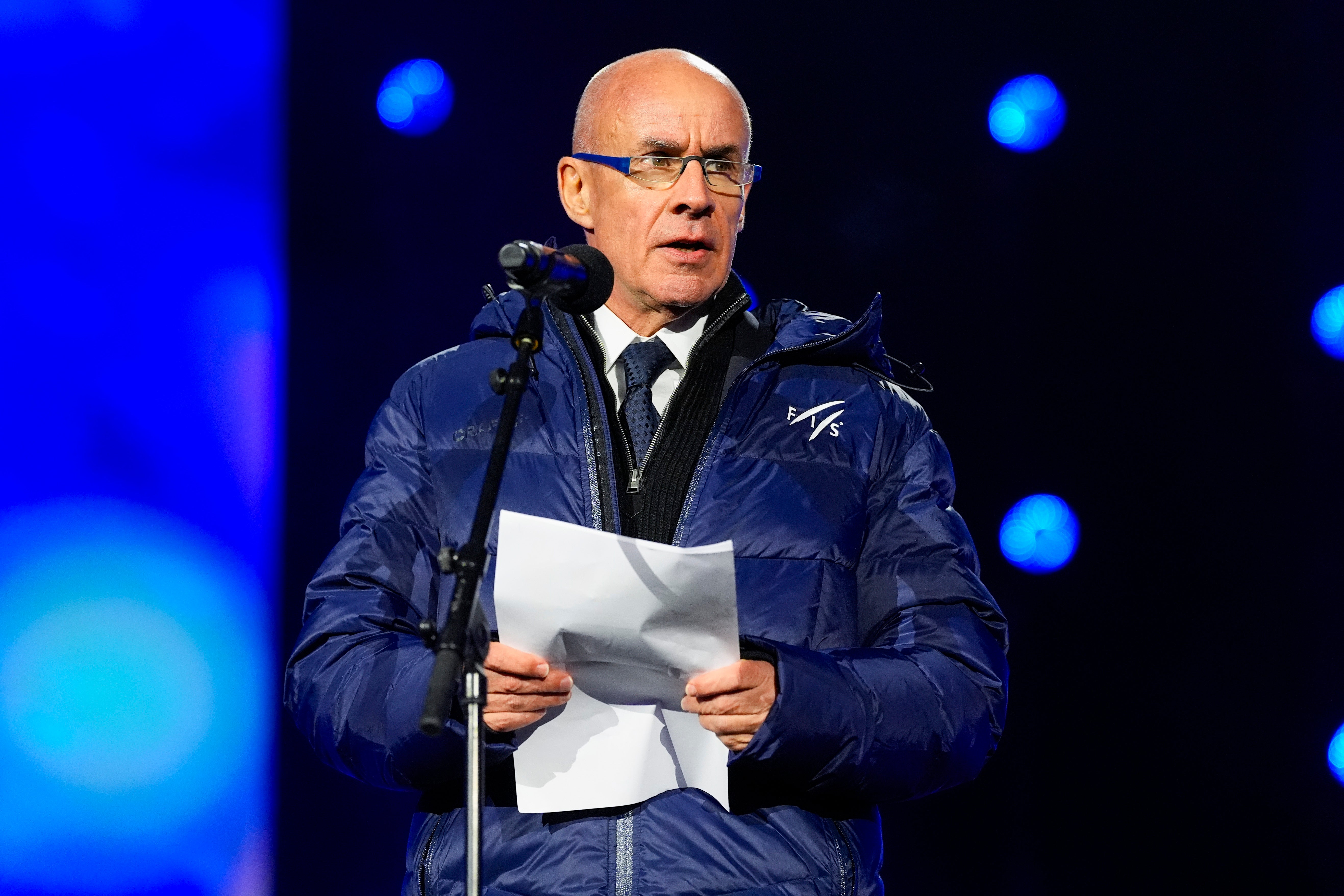

Coe is one of two British candidates on the ballot: the other is the lesser known Johan Eliasch, a Swedish-British businessman and environmentalist who heads up the Winter Olympics’ biggest sport, the Ski and Snowboard Federation. He has pitched hard on a platform of turning the Games green, suggesting the IOC should commit to conserving a rainforest the same size as each Olympic city.

Some members knew little about Eliasch before his candidacy and one was surprised he “bulldozed in” to the presidential election so soon after becoming a member last year. That is not seen as the “done thing” at the IOC, a conservative organisation where you wait your turn and earn your stripes, joining working groups and commissions to build your standing.

When it comes to its leader, the IOC has a type. Eight of the nine presidents since its inception in 1894 have been greying European men (ex-decathlete Avery Brundage, elected in 1952, was the sole exception – he was a greying American man). They usually speak multiple languages, and there are two further candidates who fit that old-world profile.

David Lappartient is the president of world cycling (the UCI), and the Frenchman is known as a hard-working “eager beaver”, one source says, who members consider a safe pair of hands. He can expect some backing from central Europe and Francophone Africa, but his CV lacks the heft of Coe and their Spanish rival candidate with a famous name, Juan Antonio Samaranch.

Samaranch is a serious contender in this election and is widely respected among the membership. He has served on a raft of Olympic commissions and is a current IOC vice-president, and he is expected to have strong backing across Europe and the Americas. He is a smooth operator and multi-linguist, skilfully illustrated last month when the Spaniard flipped between English and French in his candidacy speech.

What stands as both a blessing and a curse is the legacy of his father, Juan Antonio Samaranch Snr, a godfather figure at the IOC who served as president between 1980 and 2001. His reign did much good for the Olympic movement like ending the IOC’s men-only membership, but a damaging corruption scandal emerged on his watch and he embroiled himself in controversy with lavish spending. While the Samaranch name still carries an undoubted gravitas in the Olympic world, one member questioned the optics of installing the seventh president’s son as the 10th president of the IOC. “It’s not a family company,” they joked.

Even so, it seems Samaranch would be a trusted pick. One source said he is seen as having a “cute financial brain” and could be the best candidate to maximise broadcast and sponsorship revenues, having been involved in relevant IOC committees for several years, while another said he has been showing admirable “passion” and a “fighting mentality” in his lobbying pitches to members.

But while Samaranch may be the establishment name, he is not the favoured candidate of the current president. Public endorsements are strictly forbidden but it is an open secret that Bach’s preferred successor would be the sole female candidate on the ballot, the former Zimbabwean swimmer Kirsty Coventry, Africa’s most decorated Olympian with eight medals.

Coe and Coventry are the only Olympians among the seven candidates, but Coventry is much younger at 41, and her relative youth combined with her recent role on the IOC Athletes’ Commission should give her the backing of the small but growing group of recently retired athletes in the membership, like American sprinter Allyson Felix. All of the candidates cheered about “athlete empowerment” during their campaigns, but when it came from Coventry, the message carried real weight.

The IOC has also sought to redress the gender balance among its membership in recent years and the influx of women could also play into Coventry’s hands as she seeks to become the first female president. Though if she needed evidence of just how hard that might prove to be then she need only look at the IOC’s own web page explaining this election, which already assumes the president will be a man based on the subheadline: “When will the new IOC President start his term?”

Coventry’s role as sports minister for controversial Zimbabwean president Emmerson Mnangagwa has brought some criticism, but it does not appear to be derailing her campaign. If she can pull together a coalition of African members, women and Bach loyalists, she could provide a major challenge. The winning candidate must earn 50 per cent of the total vote, and each round of voting sees the bottom candidate eliminated, so Coventry’s best chance might come in the early rounds when the European voting bloc is split several ways between Coe, Eliasch, Lappartient and Samaranch.

That leaves two more candidates, one of whom is another serious prospect for the presidency: Prince Feisal Bin al-Hussein, the only royalty on the ballot as the brother of King Abdullah of Jordan. Prince Faisal is the head of the Jordanian Olympic Committee and has become a major player at the IOC over the past decade after serving on a number of commissions and the executive board.

His universal popularity cannot be overstated. Everyone involved with the IOC speaks glowingly about Prince Feisal, who has charisma and natural leadership to go with a strong track record in sport. He is well known for his work as founder of Generations For Peace, an NGO which promotes tolerance in areas of conflict through sport and other community programmes, and it means his “sport for peace” pitch carries genuine meaning at a time of geopolitical tension in the world.

The final candidate is Japan’s Morinari Watanabe, president of the International Gymnastics Federation and a rank outsider. Watanabe has come up with some radical ideas like hosting an Olympic Games on five continents simultaneously, and he has proposed restructuring the IOC as a House and Senate. His boldness and originality has made an impact on some members, but Watanabe faces an uphill battle to become the first Asian president of the IOC, in part because it is primarily an Anglophone organisation, albeit he does speak some English. Speaking two weeks ago, one member was surprised that Watanabe had not yet phoned them to lobby for votes.

Those 109 votes are the currency of this election. The session is being opened in Olympia, but the election itself will take place 200 miles south at a luxury resort hotel on the Costa Navarino – there is no proxy voting and members are required to attend in person. Not so long ago they cast votes on paper slips which had to be collected by younger members and counted in a process that could take several hours, but these days it is done electronically. A candidate’s national compatriots are not allowed to vote, so, for example, French members will sit out until Lappartient is eliminated. Oddly, candidates can vote for themselves.

Figures close to this election are encouraged by a strong list of candidates and yet also stress that this is a crucial moment for the Olympic movement. Just two days out, it is still hard to know who will triumph. Even the exclusive club of members with voting powers can’t be sure how the cards will fall – has anyone spoken to Princess Nora of Liechtenstein recently? And even when private discussions take place, nothing is certain. Everybody tells you who they’re voting for, and no one tells you the truth.