In the opening seconds of Netflix’s latest true-crime documentary, Fred and Rose West: A British Horror Story, a decades-old recording of a police interview crackles into life. “Things are happening in your house at the moment,” DC Hazel Savage tells Fred, her voice almost gentle, like she’s speaking to a child. “The police have been there this afternoon, and they are, in fact, digging up your back patio. We’re concerned about the whereabouts of your daughter. Is she under the patio at your house?”

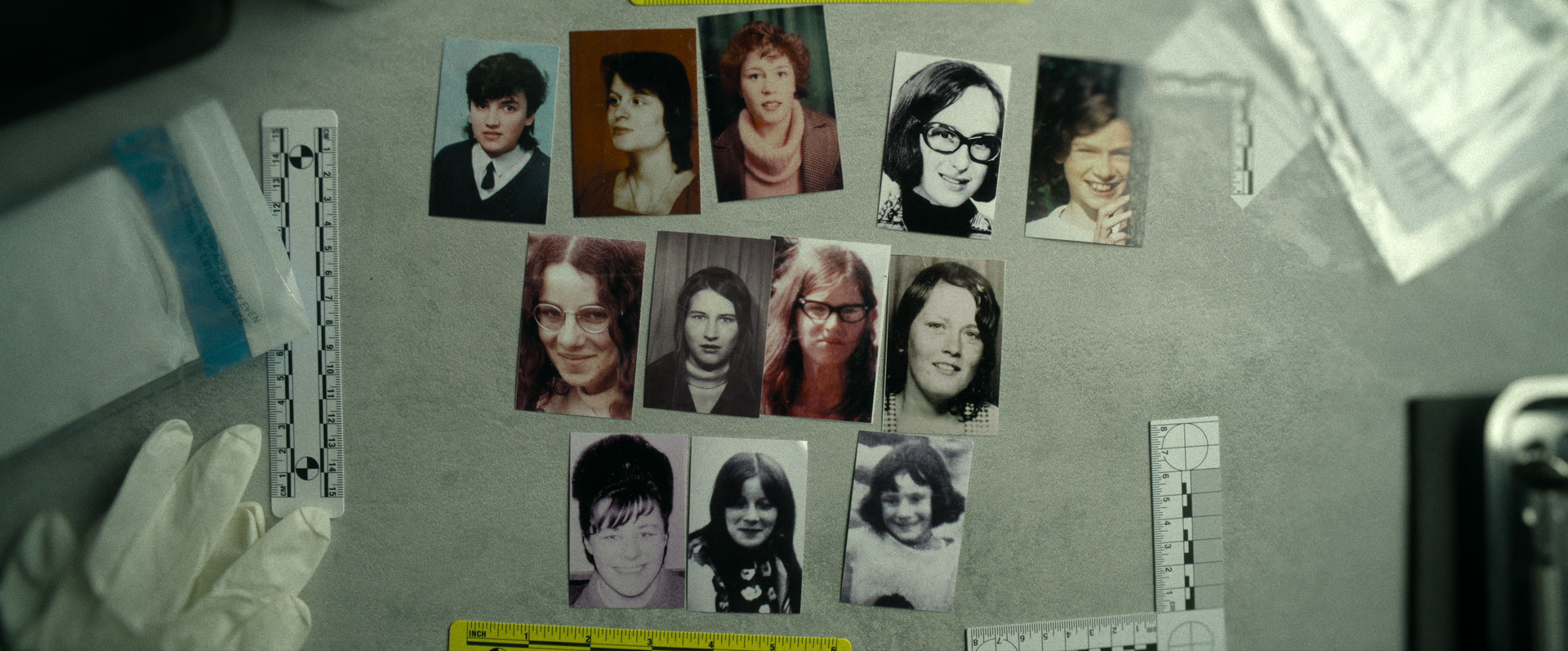

This was February 1994 and, unbeknownst to Gloucester Police, they were on the cusp of uncovering one of the worst serial killer cases in British history. They were about to realise that not only had this builder they’d taken into custody murdered his daughter Heather, cut up her body and buried her under the garden where his other children played, but he had also killed many more women and girls. While 12 bodies have subsequently been found, the total number of victims – many of whom were raped and tortured before their deaths – is still not known. In many of these attacks, Fred had an accomplice: his wife Rose.

The case stunned the world in 1994. “It is in all the minds of people of a certain age,” says documentary director Dan Dewsbury. “These were killings that had been happening, for the most part, in a terraced house in central Gloucester. Some went back as far as the Sixties and had gone undiscovered for decades. The fact that many of them were committed by a couple with children, within the walls of their family home, only added to the horror. I still remember my mum sitting me down as a child and telling me not to go off with strangers, even, shewas at great pains to emphasise, if one of them was a woman or a mother. I’m certain that the West case was on her mind when she said this.”

How, then, with a case so familiar and so entrenched in the British psyche, do you make something new? How do you avoid just needlessly wallowing in the horror and the agony. Dewsbury’s documentary, the latest in a long line of series about the Wests, arrives 30 years after Rose was found guilty of murdering 10 girls and women. Fred killed himself on New Year’s Day 1995 while awaiting trial. Netflix approached Dewsbury with the project, which is the streamer’s second A British Horror Story series after 2022’s Jimmy Savile documentary, telling him they had access to previously unseen police video and unheard audio recordings. The filmmaker was intrigued, but he wanted to do the project his way and bring a new perspective to the story, while avoiding the “salacious” approach that can plague a lot of true-crime programming.

So Dewsbury and his team tracked down people who’d never been interviewed about the case before: Dezra Chambers, sister of victim Alison Chambers; Rachel Carlyle, the first local journalist on the case; Sir Brian Leveson, the prosecutor (and later head of the Leveson Inquiry into newspaper phone hacking). Other family members of victims were interviewed too, along with lawyers, psychologists and even a lodger who lived with the Wests. The resulting three-parter is a series of original interviews combined with the rushes of previous films, all with the ultimate aim of showing the ripple effect the case had on the people who got tangled up in the Wests’ web.

“I’ve done a lot of police stuff before [including the BBC’s The Detectives: Murder on the Streets], and the culprit will get 25 years or something like that, and normally that’s where the documentary ends, right?” says Dewsbury. “But I know it doesn’t, I know that the families and people who are involved have to live with it for the rest of their lives, and try and compute what’s happened… This case affected everyone in ways that are unexpected and uncomfortable.”

The interviews are hard to watch. We see Marian Partington, the sister of victim Lucy Partington, talking about her struggle to accept her sibling’s death because it was “so brutal and meaningless”. We see Mary-Ann Mitchell, the sister of victim Juanita Mott, cry as she recalls watching their mother “crumble” at the news that her daughter’s body had been found. But it isn’t just families who are still haunted by the events. Detective Constable Russ Williams tells the camera: “The case did change me in terms of what I thought was possible – what I thought people could do to each other.” We learn that the police who were interviewing Fred, the “appropriate adult” who had to be at his side for every questioning, and Fred’s solicitor, all left the first interrogation and shared a silent group hug in the tea room, after he casually described using a bread knife to dismember the body of his daughter.

Having access to the police interviews allowed Dewsbury to illustrate the chilling drip effect of the West case. Here were local police officers, thinking they were investigating a one-off domestic murder, who slowly became aware that the case was more far-reaching than they could ever have imagined. In the interviews, Fred is calm and cocky. At one point, he giggles. The police were advised by forensic psychologist Paul Britton to allow Fred – whom Britton describes in the documentary as a “sadistic sexual psychopath” – to think he was taking part in a shared, equal conversation, so let him “smoke, wax lyrically, relax”, and ask open questions. This technique led to Fred stumbling into new confessions, at one point accidentally referring to three bodies at a point when only two had been discovered, and at another saying the dead women were “all so mixed up in my mind now I haven’t got a clue which is which”.

Dewsbury was transfixed by the police investigation, as he listened to “the flow of questioning and how on a tightrope that is … Now, we all know the end of the story because of all the victims, but it’s really easy to forget that the police started out with one person, and a confession to that, and they didn’t have any idea who anyone else was. I wanted to try to empathise with the situation that the police were in.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

The documentary also shows, crushingly, the missed opportunities along the way. The only reason the police went to dig up the Wests’ patio in the first place was because social workers who were seeing the West children – there were 10 kids in total – had heard something strange. The children kept telling them that their father would joke that, if they misbehaved, they’d end up under the patio like their older sister. Eventually, the authorities realised that no one had heard of Heather, who was indeed under the patio, since 1986.

“I do think there are huge, huge lessons here,” says Dewsbury. “We know how unintegrated the systems are still, but they were even more so in Britain at that time – with the NHS and police and social services not talking to each other.” He adds that it was important to him to shed a light on the suffering of the surviving West children. “It never gets talked about, but the kids were victims too. They were in that house for such a long time and have had to live with the legacy of that.”

Many years before the digging began in 1994, there was a major sliding doors moment in the case. In an archive interview, Caroline Roberts, a former nanny of the Wests, recounts being abducted and sexually assaulted by Fred and Rose in 1972, when she was just 17. She went to the police at the time but appallingly, the case only went to the magistrate’s court, and the Wests got away with a £25 fine each. If only this traumatic incident had been taken more seriously, the Wests may never have gone on to kill so many people.

Roberts was a witness in Rose’s 1995 trial, and it was because of her evidence that Rose was convicted, as she was able to describe how the Wests acted together, not just Fred alone. “I don’t think people realise how much guilt survivors feel,” she says in a tearful interview. “I realised they started killing [together] three months after my court case in ’72… so given the opportunity to actually be a witness against her kind of set me free a little bit. Even though all my little secrets and my demons were out there on view to the world, I actually, for the first time in my lifetime, felt self-respect. I went in there to get justice for the girls that didn’t make it.”

For Dewsbury, watching Roberts’ interview was “heartbreaking”. “She should feel no guilt whatsoever,” he says. “That system, I mean it’s similar now, but it seemed back then like no one listened to her. She had to live with what happened to her, the violent sexual assault that happened to her, for 23 years before the trial.”

Roberts died of cancer in 2016, so Dewsbury went to her family instead to make sure they were happy about her previous interview being used in the show. “I really, really wanted to try to do this in the way it should be done,” he says. Taking on the project, he says, was contingent on Netflix backing him to do that.

It seems to be a stark contrast to how Netflix’s true-crime drama (and mega-hit) Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story was handled. The 2022 series, about the American serial killer and sex offender, was heavily criticised by the families of victims, who had not consented to the show being made and who said its release was “retraumatising”. Whether intentionally or not, it also romanticised the killer, who was played by Hollywood star Evan Peters. After the drama aired, the spectacles Dahmer wore in prison were put up for sale for $150,000. A recent news story about Rose West’s underwear being sold to the True Crime Museum in Hastings has obvious echoes of this. Dewsbury, on the other hand, wanted to completely avoid this sense of lurid fascination in his own series.

“Look, I wouldn’t be doing this if I didn’t believe I could do it with integrity, and if it hadn’t been proven that Netflix would allow me to do it [that way],” he says. “Every person who is involved in that case has had a phone call from me… The reason why I stand by this series is because I know I’ve done it the right way. I’m not a salacious person. I want to bring the biggest audience to this, but I also want to make that audience understand there is a different POV. There is an audience who watch a lot of true crime. That is the audience that I wanted to change.”

He wants the long-lasting impact of the Wests’ crimes to linger in viewers’ minds when they finish the documentary. “Life isn’t tied in a bow, and you can’t just switch off and walk away… I want [viewers to] remember the fact that these people have had to go through something terrible. It’s not a funny story to me. It’s not a piece of culture, or whatever you want to want to call it. I’m not interested in that museum or anything like that. What I’m interested in is hearing these people’s stories and trying to tell them with emotion and integrity.”

‘Fred and Rose West: A British Horror Story’ is out now on Netflix