This story is part of an investigative series and new documentary, The A-Word, by The Independent examining the state of abortion access and reproductive care in the US after the fall of Roe v Wade.

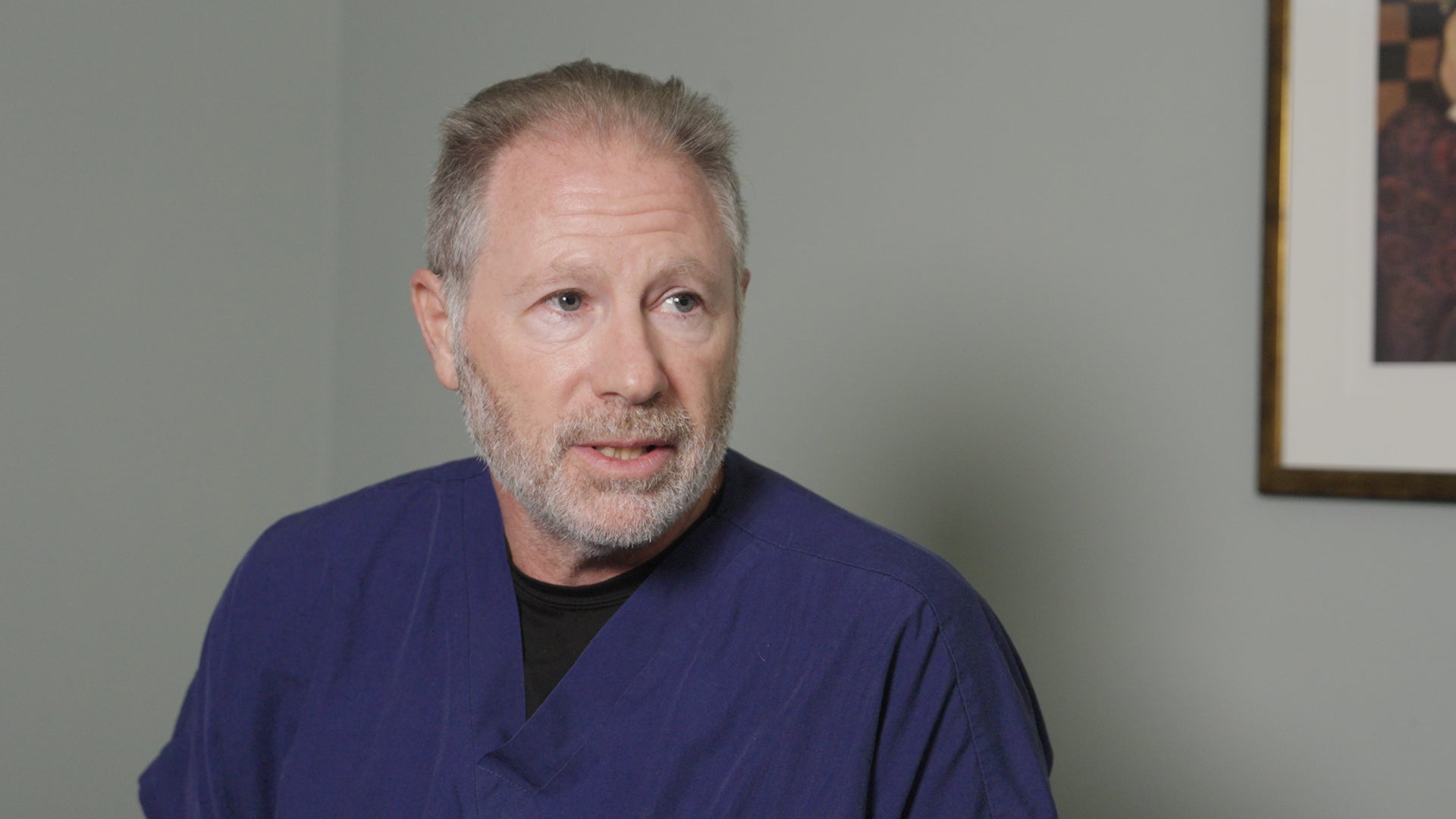

Dr Aaron Campbell holds his gun as he accelerates towards the abortion clinic where he works.

Anti-abortion protesters who camp outside recognize him, although he uses different rental cars to confuse them. As his tires squeal around the corner, they surge towards the vehicle. “The killer has arrived,” one shouts.

The staff at Bristol Women’s Health Clinic, who are always notified of his arrival in advance, rush him in safely through a back door.

“When I pull up to the clinic, I typically will hold my firearm, finger off the trigger, but ready to go if I feel like I have a threat,” Dr Campbell tells The Independent between procedures, his pistol still visibly tucked into his scrubs.

This is surgery day at an abortion clinic in Bristol, Virginia, which lies on the country’s simmering fault lines ever since the 2022 Dobbs decision overturned Roe v Wade and ended nationwide access to abortion.

Bristol straddles two states: Virginia, which allows the procedure and Tennessee, which bans it with very limited exceptions.

That makes this innocuous red brick building, located less than half a mile from the Tennessee state line, the closest surgical abortion provider for swathes of the southeast, where many abortion bans are in place.

“I never thought we would be living in this reality,” adds Dr Campbell, who had to give up the health clinic in Knoxville, Tennessee founded by his father after Dobbs made his work impossible.

The parking lots of abortion clinics across the US have become their own frontlines, with anti-abortion protesters exercising their legal right to protest by trying to coax, dissuade and harass those trying to get an abortion. Sometimes that can tip over into violence.

Violence against abortion providers rose in 2022, the year Roe fell and the most recent year of data available. According to the National Abortion Federation’s latest report, arson attacks doubled from 2021 to 2022 (jumping from two to four), while stalking incidents more than tripled. Burglaries increased from 13 in 2021 to 43 in 2022.

“The data is proof of what we have known to be true: anti-abortion extremists have been emboldened by the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade and the cascade of abortion bans that followed,” Melissa Fowler, the NAF’s chief program officer wrote in the report.

The Independent’s The A-Word documentary team spoke to multiple abortion providers across the US, and they shared that they’d encountered violence for decades but that heightened tensions and an increased number of patients at limited providers post Dobbs made the threat feel more pronounced.

“Anti-abortion extremists were emboldened and traveled to states where abortion remained legal to target clinics there,” reads the NAF report findings.

“These people that show up to these clinics are unpredictable and dangerous,” Dr Campbell says, talking about the anti-abortion protesters he has encountered while traveling for work across multiple states.

The number of stalking incidents jumped ninefold between 2021 and 2022 in protective states, meaning those with abortion rights, from eight to 81. Bomb threats doubled and a Californian Planned Parenthood clinic was firebombed.

Just a few weeks after the draft Dobbs decision leaked, a new clinic in Casper, Wyoming got broken into and set on fire. The arson attack caused hundreds of thousands in damage and delayed the clinic opening for nearly a year.

Since it began gathering statistics of violence against abortion providers in the 1970s, NAF has recorded 11 murders, 42 bombings, 200 acts of arson, 531 assaults and nearly 500 clinic invasions. They have also documented thousands of other incidents of criminal activities directed at patients, providers, and volunteers.

In November 2015, a gunman killed a police officer and two people accompanying friends to a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs. In the 1990s there were several instances of bombings of abortion clinics.

Dr Campbell, who has a small coat hanger tattoo on his arm, always carries a firearm when he is at a clinic. “Tiller was the last but he was not the first,” Dr Campbell says, referring to famed doctor and abortion provider George Tiller who was shot and killed by an anti-abortion activist while attending church in Wichita, Kansas in 2009.

“I suspect there will be more at some point, and I don’t want that to be me,” Dr Campbell continues.

One of his medical colleagues out west was so worried about being assassinated he wore a bulletproof vest at work.

“That’s until he started getting cards in the mail from anti-abortion people and protesters,” Dr Campbell adds, looking exhausted.

“They read: don’t worry with the bulletproof vest, because we’re going to go for a head shot.”

The security guard at Presidential Abortion Clinic in Miami, Florida keeps a watchful eye over the parking lot for any trespassers or anything unusual.

Back in 2005, the clinic was targeted in an arson attack. Now with the state banning abortion at just six weeks, they’re even more conscious of being a target.

Resident OB-GYN Dr Daniel Sacks, who also has his own private practice, says that protesters turned up at his house, and his clinic, even before the Dobbs decision.

“They were dropping letters to my neighbors saying ‘this guy kills babies’,” he says.

“I met with law enforcement and took some precautions… put security protocols in place.”

The only people permitted to enter the clinic are patients. As well as security guards, many abortion providers now have clinic defenders, volunteers whose sole role is to protect patients from driveway to the front door of the clinics.

Back at Bristol Women’s Health, Barbara Schwartz and Kimberley Smith, who founded State Line Abortion Access, a charity assisting people seeking abortions, escort patients from their cars to the door of the facility through what they call the “gauntlet”.

Smith explains how they shield terrified patients with large rainbow colored umbrellas to protect them from the glare of the body cams the protesters are wearing.

“We try to be the Walmart greeter of the parking lot,” Schwartz continues, showing her tattoo she got after Dobbs: a uterus accompanied by the words “aid and abet”.

“We want to exude hospitality and normalcy, too, just communicating through body language, and our tone of voice that we are the normal people and you are safe here.”

The protesters outside maintain they are peaceful and keeping within the law (it is a federal crime to obstruct people from reaching reproductive health care). They cannot pass a certain mark, and if they try to obstruct patients walking in, they are shooed out of the driveway.

Mostly they stand around next to posters of fetuses, their chants of “we are begging you not to murder your child” forming a constant wall of sound.

But the anti-abortion protesters do also try to intercept cars before they are able to turn into the clinic, holding signs reading “turn back” at nearby traffic lights.

They also attempt to deliberately confuse patients, say Schwartz and Smith, by dressing in similarly coloured high-visibility vests as the clinic’s escorts and carrying the same multicolored umbrellas.

Once the patients are inside, the protesters often turn their attention to family members and friends who, for security and privacy reasons, are not permitted to enter the clinic and so are forced to wait outside.

On the sidewalk outside the Bristol clinic, a young man called Jonathan, holding a bible and poster of a fetus, engages in a tense altercation with one male companion of a patient who said he drove her 10 hours for the appointment.

“You are an accessory to murder,” Jonathan shouts at the patient’s friend, who walks over to implore him to leave the women alone.

“Don’t shout ‘You’re going to hell!’ at them. Don’t come on so hard,” the companion begs, with little effect. “It’s hard enough that they are here. The choice is hers.”

Inside the Bristol clinic, it is noticeable that every window is covered to ward off prying eyes and ensure the safety of their patients and staff.

More than 95 percent of their patients are from interstate, says Karolina Ogorek, the clinic’s administrator, with patients driving all day from as far away as Mississippi, Louisiana and Florida to get there.

The clinic has quadrupled its number of surgery days each month to accommodate the growing demand as more bans are implemented.

“Sometimes we work on Sundays,” Ogoreksays. “We do evening clinics where we have been here until 9pm because somebody is stuck in traffic or they can’t get off work until a certain time.”

The clinic is also facing calls for it to be shut down. Ogorek says some protesters are trying to pressure the building’s landlords. Last year the staff said anti-abortion activists from Texas traveled to Bristol to lobby the authorities to use local ordinance laws to shutter the clinic.

That has made her more nervous and concerned for her personal safety. When Ogorek enters the parking lot, she pauses “to see if anything looks different”. She specifically drives a car which blends in, checks for packages outside her home every day and scans restaurants for protesters she knows.

“Who has to pull up to work and check if any window has been cracked or smashed or if there are boxes outside that shouldn’t be there?” she asks, with a note of desperation.

There were three anthrax/bioterrorism threats received by abortion providers in protective states in 2022, three incidents of arson and 57 hoax/suspicious packages received, according to NAF data.

“It’s just become part of how I live. That’s just to protect myself, to protect my own mental health,” Ogorek says. “We have to always be hyper aware.”