Parts of the Great Barrier Reef have suffered the steepest annual decline in live coral cover following the worst bleaching events in nearly four decades.

The Australian Institute of Marine Science, or Aims, said that two of the three areas monitored by researchers since 1986 have suffered coral losses this year.

The hard coral cover on the reef has declined largely due to heat stress from climate change. This heat stress has sparked mass bleaching events, which have been worsened by cyclones, flooding, and outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish.

The latest findings are a warning that the Great Barrier Reef faces a “volatile” future and may reach a “point from which it cannot recover”.

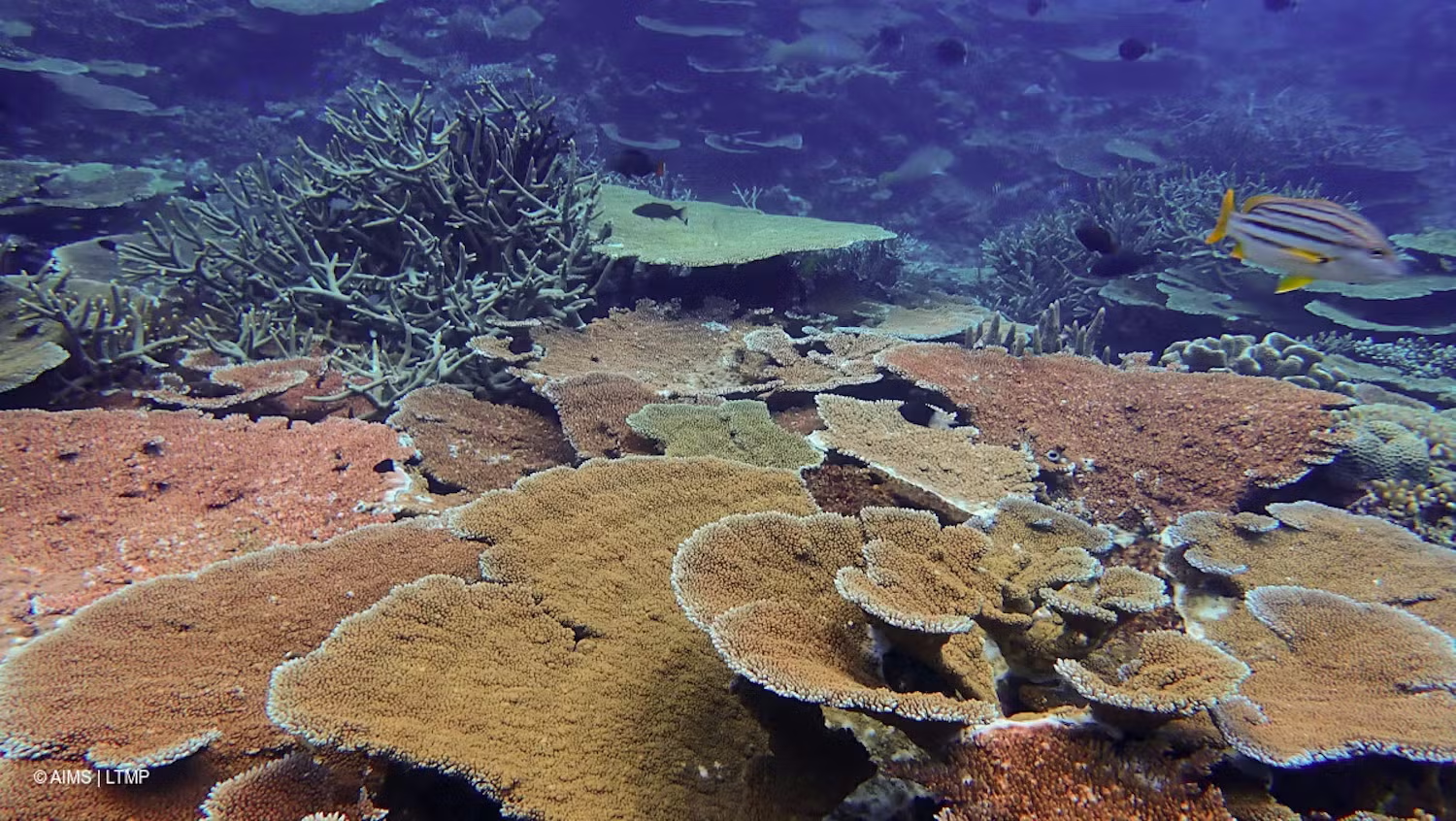

The Great Barrier Reef, located off the northeast coast of Australia, is the world’s largest living coral reef system and one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet.

Stretching across 2,400km off the Queensland coast, it comprises thousands of individual reefs and hundreds of islands made of over 600 types of hard and soft corals.

Aims surveyed 124 coral reefs between August 2024 and May 2025 and found that coral cover had dropped sharply after a record-breaking marine heatwave in 2024, “prompting grave fears over the trajectory of the natural wonder”.

“We are now seeing increased volatility in the levels of hard coral cover,” said Mike Emslie, head of the institute’s long-term monitoring programme.

“This is a phenomenon that emerged over the last 15 years and points to an ecosystem under stress.”

Aims says repeated mass coral bleaching is becoming more frequent as the world warms.

Coral bleaching is a stress response in which corals expel the algae that give them colour and energy, turning white because the water it lives in is too hot and risking death if conditions don’t improve.

Mass bleaching was extremely rare before the 1990s. The first two major mass bleaching events weren’t recorded until 1998 and 2002.

In the years since, Aims noted, the Great Barrier Reef has “experienced unprecedented levels of heat stress, which caused the most spatially extensive and severe bleaching recorded to date”.

This was “the first time we have seen substantial bleaching impacts in the southern region, leading to the largest annual decline since monitoring began”, Dr Emslie said.

In the wake of the latest mass bleaching event in 2024, aerial surveys showed around three quarters of the 1,080 reefs assessed had some bleaching. And on 40 per cent of those reefs, over half the corals had turned white.

It was the fifth mass bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef since 2016 and had the largest spatial footprint recorded, with high to extreme bleaching prevalence across the three regions, Aims CEO Professor Selina Stead said.

Despite the significant losses, Aims said the Great Barrier Reef still had more coral than many other reefs worldwide and remained a major tourist attraction.

“It’s possible to find areas that still look good in an ecosystem this huge,” Aims said, “but that doesn’t mean the large-scale average hasn’t dropped.”

The Great Barrier Reef is not on Unesco’s list of endangered world heritage sites, though the UN recommends it should be added.

Australia has lobbied for years to keep the reef, which contributes billions of dollars a year to the economy, off the list as it could damage tourism.