My aim is to unsettle by showing what’s real and what isn’t,” says Grayson Perry, all messy hair, stubbled chin, crumpled T-shirt and paint-smeared trousers, with only the shocking-pink fingernails on his rough artisan’s hands showing a hint of “Claire” – his famous cross-dressing alter ego.

In his north London studio it is almost a shock to see the artist so blokeishly casual, just two weeks after I’d witnessed his dramatic entrance at lunch in Mayfair’s Arlington restaurant in floral dress, coloured tights, shining lipstick and red high heels. His voice is powerful, almost gravelly, alternately angry and funny, as he explains why the role of the artist is to provoke – on beauty, class, gender, money, sex and even AI.

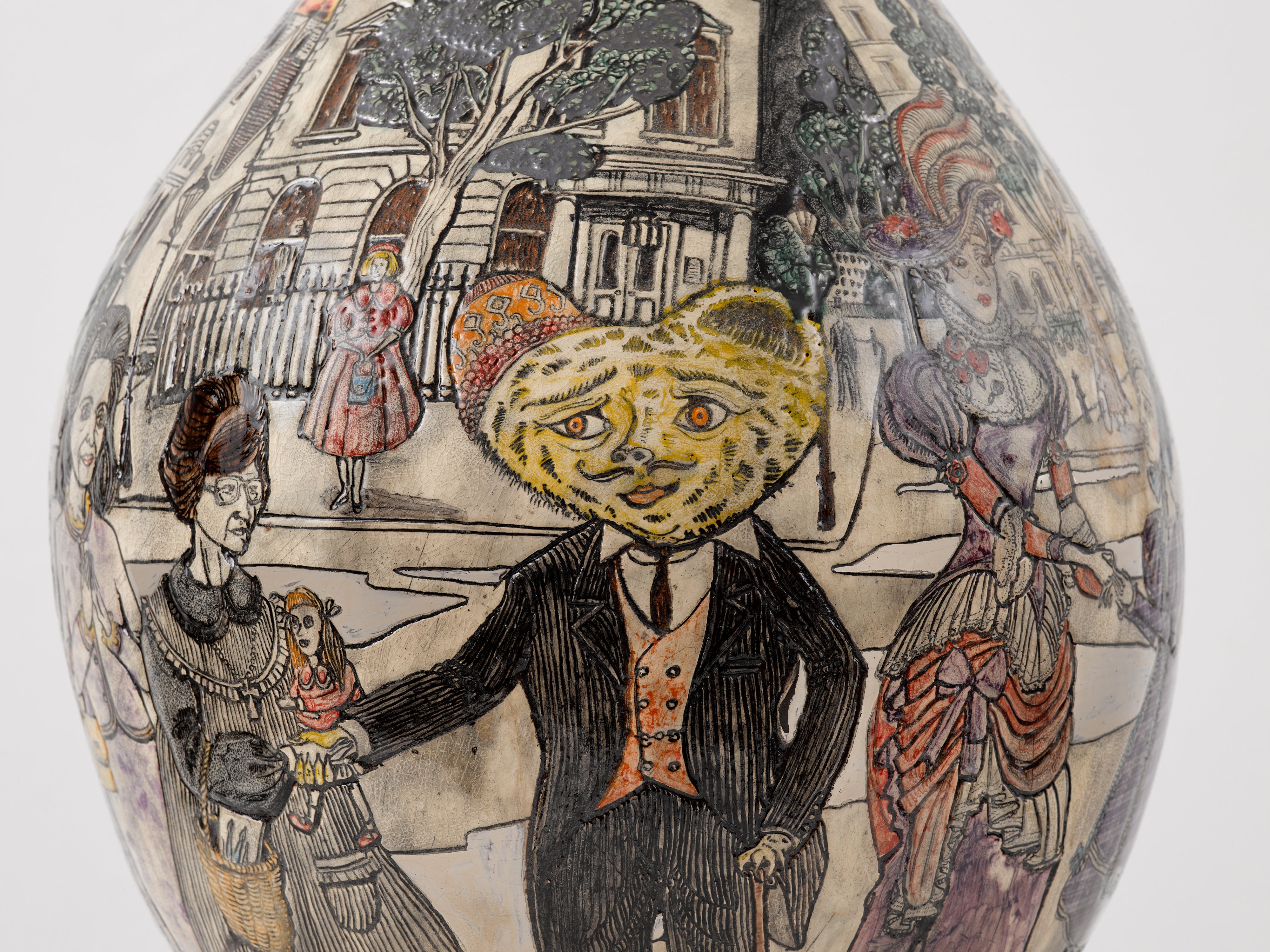

On top of a large kiln for baking his pots is a small glazed figure in a dress with a protruding erect penis. A prototype tapestry hangs above him as he talks about his show at the Wallace Collection in Marylebone. Delusions of Grandeur is the biggest exhibition of his life, neatly coinciding with the 65th birthday of this celebrated potter, transvestite, embroiderer, TV personality, biker and soon-to-be musical theatre star of his own life story. “I call myself a conceptual artist masquerading as a craftsman,” he says.

This knight of the realm, national treasure and social disrupter is showing 30 new works, from pots to tapestries, collages to a bronze helmet, a gun, fabulous dresses and a spectacular wooden bureau (which alone took three years to make and then decorate with dozens of portraits). This eclectic collection is as colourful, startling, original and beautiful as the Liberty dress he says he will wear for the show’s opening party.

Perry has a gift for sparkling verbal one-liners and visual showstoppers – aesthetic and disruptive. It is what he has been doggedly doing for 40 years ever since he seemed to emerge from nowhere, the man in a dress who makes ceramic pots, to become the surprise winner of the 2003 Turner Prize. Twenty years later, arise Sir Grayson, kneeling before Prince William, the first man to be knighted in a frock.

“My job is to trust my intuition and often it’s in your gut and in your body and in your emotions. That is why I loved therapy because it gave me this sort of insight and awareness into my bodily reaction to the world. Being an artist, to a certain extent, you’re on a kind of class elevator,” he says. It has been quite a ride.

His upbringing in Essex was violent and deprived. His stepfather hit him. He was a milkman who moved in with his mother and is disdainfully never mentioned by his name in Perry’s autobiography, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl – yet he comes across clearly as hideously abusive.

Grayson was 13 when he first became aware of painting during one of his rare childhood museum visits: “I remember [the French rococo artist François] Boucher’s Madame de Pompadour when I was sort of a nascent transvestite and so would have been quite drawn to the frock.”

His inspiration for the latest show is wilfully odd as he is clear that he has never much liked the Wallace Collection, a 19th-century bequest to the nation of paintings, sculpture, furniture, armour and porcelain in a grand London house behind Oxford Street. It’s for this reason that he invented an entirely fictional fellow exhibitor, Shirley Smith, a woman with an obsessive crush on the Collection, who believes herself to be its rightful heiress. She is the latest alter ego or triggering device for Perry who has a very long history of identity swaps, most famously morphing into Claire, whom he dresses spectacularly in drag. His childhood teddy bear, Alan Measles, often makes appearances in his art.

In effect, Shirley is the godmother or co-pilot of this show, merging with and inspiring Grayson as they perform a sort of artistic pas de deux in the first room with works by her (actually made by him) as well as his own signature pots and other pure Perry works. “I wanted Shirley as a kind of poster girl for how art can sustain your life even when you’ve got nothing.”

Different parts of Shirley’s biography are written into Grayson Perry: Delusions of Grandeur. “I’m the fantasy person that she thought she was and there are layers entwined,” he explains. There are also poems by Shirley (or rather him) and on the audio guide an actor gives her a voice. A little confusing at times, perhaps, but always dynamic.

It was three years ago that Perry was invited to exhibit by the Wallace, which is best known for its paintings by the rococo geniuses Boucher and Jean-Antoine Watteau, with their erotically charged women in stunning silk gowns. Ah, you think, that is why Perry is here. But he’s not having that. “I’m actually more of a kind of northern European Renaissance guy, more of a Van Eyck than Van Dyck,” he says by way of explanation.

The Wallace is also famous for its 18th-century Sèvres china, very different from Perry’s politically charged pots. “I have a revulsion of Sèvres because everyone was like, ‘Oh, I love the Sèvres.’ But whenever I look at it, I think Eastbourne charity shop.”

In the show is a ceramic pot called Computer Sick. “I wanted it to be elaborate and layered, and I started using AI a bit to make images. It is about the age of computers and the relationship to the handmade. It has a child on the lid looking at an iPad.” But before he really gets going on this intellectual riff, he pulls the rug on his own pretentiousness. Alongside palm trees and other images on the pot is a striking image of a red sun. “It is what you call in art a compositional element. Art critics try desperately to read into everything but for me in this case I just needed some red there!”

So does he encounter prejudice? “Oh yes… that I’m a silly drag queen. Then people get a bit of a shock when they hear me talk. Then they ask, ‘Why aren’t you an MP?’” Passionate about social change and injustice, he is Labour to his core: “I’ve long been a supporter of Keir.” He is well versed in dealing with many misconceptions. For example, most transvestites are heterosexual, he patiently explains. He does not want to get too deep into the politics of gender identity. “It’s become so much of a hot potato. I try to keep out of it.”

Perry gives a whistle-stop tour of his show through a digital version on his laptop. From fantasy photographs to graphics to tapestries to a neo-medieval helmet fully functional and forged with hammer, fire and anvil. “I steal from everyone,” he jauntily confesses – beads, plywood, works inspired by everyone from Picasso to Picabia, rococo portraits, tapestries and family trees.

He will be in full flight on all of his new works and also his musical-theatre persona, as he is midway through writing and having singing lessons for his acting debut in the musical that he has been working on with Richard Thomas, the composer of Jerry Springer: the Opera. He will explain more at the Hay-on-Wye literary festival this summer.

For all the lightness and accessibility to his art, anger is a weapon that he keeps at the ready. One of his pots is called What a Wonderful World. “It’s about posh people and being in west London. I have this sort of deep prejudice against west London because I always feel that waves of entitlement come wafting off everybody. It kind of starts at Oxford Street, going into Bayswater, Notting Hill and Kensington.

“That kind of international beige super-wealth. It annoys me, as quite often these very wealthy places become cultural deserts. I go to a collector’s house and they are lovely, in lovely parts of town, but the cleaners have cleaned the house so well there’s no clutter, just ornaments arranged in a neat row and they are perfectly dusted.”

But as ever with Perry, nothing is ever quite as it seems. “Obviously I also love the super-rich because they buy my work! Those oligarchs have got rooms to be filled. But there is also an annoyance at the way people use London to park their wealth without actually contributing to the society and to the tax base. If you are going to use this country as a bank at least pay the security guards!”

He once did a show called Super Rich Interior Decoration “to take the piss out of the collector. He loved it. It was also the most profitable show I ever did.” He says the anger that has fuelled so much of his work probably came at some point from his parents. “Now I am angry at society, certain groups I get angry at. It’s enjoyable. I enjoy having a grudge.”

If he had not found success as an artist he thinks he might have been an advertising copywriter. “I knew I had a facility for a kind of deep cynicism and a good imagination.” It has been a long journey since he first sold his pots in an early show for £35 a pop. He did not hit the £1,000 mark until he was 15 years out of college. Now they retail at £150,000. One of his pots sold for just over a million dollars.

And so to Claire and his transvestite identity. “I often go out in an entire outfit: shoes, dress, coat, glasses and handbag. I kept the two [identities] apart for many years so Claire wasn’t part of my art so much. And then as I became more confident as a cross-dresser at some point – I suppose just before the Turner Prize – they came together.”

Did it take courage? “I think adrenaline addiction is the word. I have always been an adrenaline addict. Adrenaline is a great aphrodisiac. Dressing up and going on stage, it’s a big kick – that’s why I do it. I get off on it.”

The other day someone came up to him and asked if he was doing anything exciting. “I said: ‘I’m 65. I am Grayson Perry. Everything I do is exciting.’ It’s how I sculpted my life.”

He returns to the next pot. “This one’s called Sexual Fantasies, set in the olden days, which is a very common thing with us in the fetish community.” He is at ease with his fetishism and has thought about it deeply. “Most transvestites would probably choose to live in the mid-Victorian era. For the clothes obviously. It was pre-Freud, so cross-dressing wasn’t sexualised in the public imagination.”

And he is critical of those who don’t follow suit. “The academic classes can often be a bit dead from the neck up. I am full of admiration for their knowledge but as Trump has proven there are other ways of being sophisticated. And this is the mystery to how the f*** could people vote for him. He speaks in a certain visceral animal level that works. And you just don’t get that in Martha’s Vineyard.”

With Perry there is courage and curiosity. There are some reassuring memes, the reappearance as an image of Alan Measles, who has been a constant totem in his life and art. But do not think of Alan as sentimental or even as a cuddly toy, think lifebuoy to hang onto in a childhood shipwrecked by abuse, poverty and fear in a working-class council home with no books. His teddy was his go-to in a world of pain and impoverishment.

Perry is as eloquent on mores or manners of 18th-century philosophy as he is on the imagery in Larkin’s poems. He is a magpie of knowledge, high and low. Think academic with attitude – and definitely not academic from any ivory tower. He is more public-ready philosophical brawler than a Baudelaire high priest. He is also ready to fight with his fists if confronted.

Today, after much therapy, he is a genius at explaining art and himself: his childhood of being whacked around the head by his stepfather; his teddy helping him survive a horrifically choppy sea. “You don’t have a kind of ‘I’ll invent a strategy to deal with my emotional abuse’. It kind of happens and then 30 years later you start to unpack it.”

His second memoir was called The Pre-Therapy Years. And the story it tells is raw and painful. “I’m much more conscious of it, the emotional resonance is still there and I could well up talking about it quite easily.” Alan Measles carried a lot of emotional freight. “I dumped all of my positive attributes into him for sort of safekeeping… I think the big journey I made, particularly post-therapy, is bringing them all back to me. So he’s a husk now. He’s a guru. I call him the guru. I have his people who’ve gone forth, that’s my current metaphor and that is what therapy is all about.”

This small teddy – the original is still battered but intact in his studio – gives him valour and validation. “That’s why I invented him. I needed a language and I’ve made countless works of art and I come back to him. He is part of my iconography.” Alan Measles has – in his art – met Trump and Farage and has even been knighted by the King when Perry got his gong. His name? Measles stems from when Perry was three and in bed with the virus. Alan was his best friend, whom he still sees.

And so Grayson Perry travels and explores the human condition through pots and guns and imagery seen through the searing fire of his past. He has changed the language of art – not that his sometimes chippy, über-critical eye would let him see that. This is how he’d rather see himself: “It feels like I am a kid still shouting into the void.”

‘Grayson Perry: Delusions of Grandeur’ is at the Wallace Collection from 28 March until 26 October

-Richard-Ansett-shot-exclusively-for-the-Wallace-Collection-London.jpg?trim=1832,0,1352,0&width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)