A mass grave site in Tehran, where thousands executed in the aftermath of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution were buried, is being paved over to create a car park.

Satellite images reveal that Lot 41 of the sprawling Behesht-e Zahra cemetery, a desolate patch of sand and trees, is being covered with asphalt, likely entombing the remains of those interred there.

For decades, this area served as the final resting place for opponents of Iran’s nascent theocracy, executed by gunpoint or hanging.

The site has long been under surveillance, with cameras monitoring for any signs of dissent or remembrance at what officials have termed the “scorched section”.

State-sponsored demolition has previously occurred here, with grave markers vandalised and overturned. Iranian officials have acknowledged the recent decision to construct the car park, though they have offered no specific details regarding the identities of those buried beneath.

A United Nations special rapporteur in 2024 described Iran’s destruction of graveyards as an effort to “conceal or erase data that could serve as potential evidence to avoid legal accountability” over its actions.

“Most of the graves and gravestones of dissidents were desecrated, and the trees in the section were deliberately dried out,” said Shahin Nasiri, a lecturer at the University of Amsterdam who has researched Lot 41. “The decision to convert this section into a parking lot fits into this broader pattern and represents the final phase of the destruction process.”

Last week, both a Tehran deputy mayor and the cemetery’s manager acknowledged the plans to create a car park on the site.

“In this place, hypocrites of the early days of the revolution were buried and it has remained without change for years,” Tehran’s deputy mayor Davood Goudarzi told journalists in footage aired by state television.

“We proposed that the authorities reorganise the space. Since we needed a parking lot, the permission for the preparation of the space was received. The job is ongoing in a precise and smart way.”

Satellite images show construction

The satellite photos show the work began in earnest at the start of August. An 18 August image shows about half of Lot 41 freshly paved over, with construction material still on site. Trucks and piles of asphalt can be seen at the site, suggesting work continued.

The reformist newspaper Shargh quoted Mohammad Javad Tajik, who oversees the Behesht-e Zahra cemetery, as saying the parking lot would help people visit a neighbouring lot, where authorities plan to bury those killed in the Iran-Israel war in June.

A major airstrike campaign by Israel killed prominent military generals and others, with government officials putting the death toll at more than 1,060 people killed, with an activist group putting it at over 1,190.

The decision to repurpose the graveyard appears to clash with Iran’s own regulations, which allow for a cemetery to repurpose land where internments took place after more than 30 years — as long as families of the dead agree with the decision.

An outspoken lawyer in Iran, Mohsen Borhani, publicly criticised the decision to pave over the graveyard as neither moral nor legal in an interview with Shargh.

“The piece was not only for executed and political people. Ordinary people were buried there, too,” he reportedly said.

It remains unclear whether human remains sit beneath the layer of asphalt or if Iranian authorities moved the bones of the dead there. However, Iran has destroyed other graveyards in recent years for those killed in its 1988 mass execution that saw thousands put to death, leaving their bones there.

Authorities have also vandalised cemeteries for the Baha’i, a religious minority in the country long targeted, and those home to protesters who have died in recent nationwide protests against Iran’s theocracy from the 2009 Green Movement to the 2022 Mahsa Amini demonstrations.

“Impunity for atrocities and crimes against humanity has been building for decades in the Islamic Republic,” said Hadi Ghaemi, the executive director of the New York-based Center for Human Rights in Iran.

“There is a direct line between the massacres of the 1980s, the gunning down of demonstrators in 2009, and the mass killings of protesters in 2019 and 2022.”

Massive cemetery is the final resting place for many

Behesht-e Zahra, or the “Paradise of Zahra”, opened in 1970 on what was then the rural outskirts of Tehran. As hundreds of thousands of Iranians flooded into the capital under the shah as the country’s oil wealth skyrocketed, pressure on Tehran’s cemeteries had grown to a point that the burgeoning metropolis needed a place for all of its dead as well.

The cemetery has long been a resting place for some of the most famous Iranians since – and a point where history turned for the country.

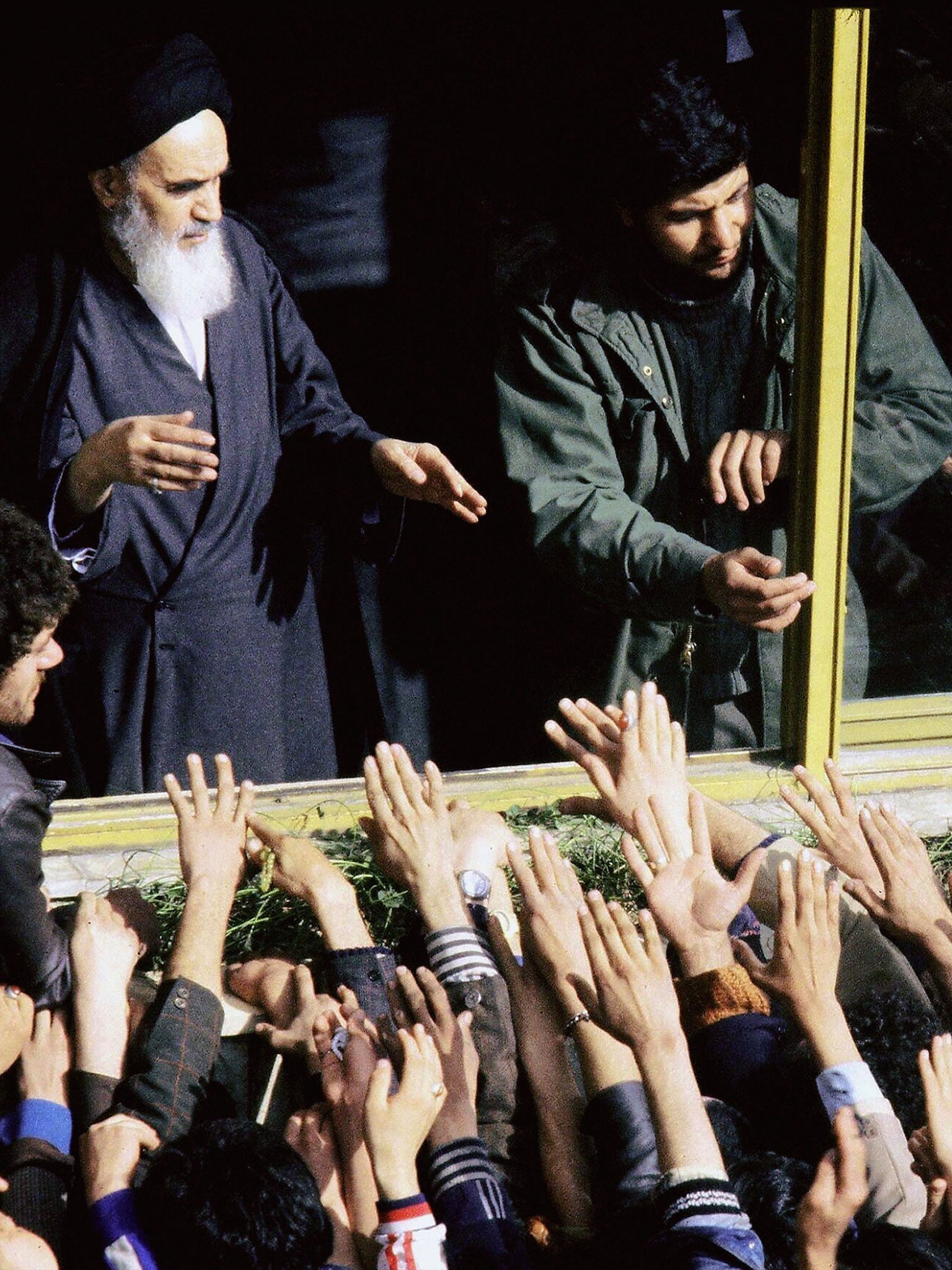

On his return to Iran in 1979 after years in exile, Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini traveled first to the cemetery, where some of those killed in the uprising against the shah had been buried. Khomeini’s cleric courts later issued death sentences for those now interred at Lot 41.

After his death in 1989, Iran built a towering, golden-domed mausoleum for Khomeini connected to the cemetery. As Behesht-e Zahra grew, Lot 41 found itself surrounded by an ever-expanding number of lots for burials.

Nasiri said his research with others suggests there are 5,000 to 7,000 burial sites within Lot 41 of those Iran “considered religious outlaws,” whether communists, militants, monarchists or others.

“Many survivors and family members of the victims are still searching for the graves of their loved ones,” Dr Nasiri said.

“They seek justice and aim to hold the perpetrators accountable. The deliberate destruction of these burial sites adds an additional obstacle to efforts of truth-finding and the pursuit of historical justice.”