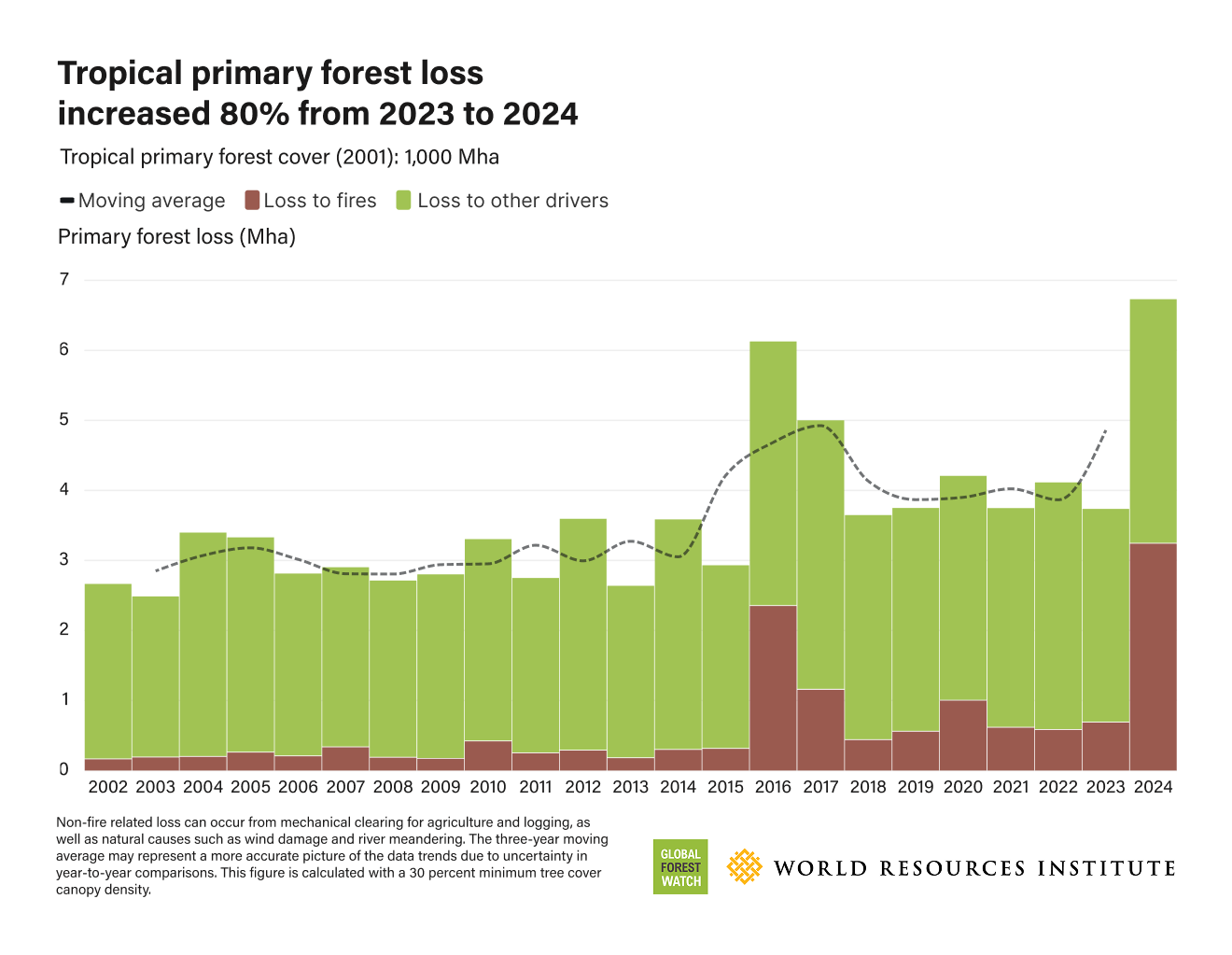

Global forest loss surged to record levels in 2024, with wildfires destroying 6.7 million hectares of tropical primary forest – nearly double the previous year’s – according to new satellite data.

For the first time, fires, not agriculture, were the leading driver of tropical forest loss, according to data released by Global Forest Watch, as experts called it a “global red alert”.

The new figures, based on analysis by the University of Maryland’s GLAD Lab and published on the World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch platform, reveal the devastating toll of fire-fuelled deforestation on both the climate and vulnerable communities around the world.

“This level of forest loss is unlike anything we’ve seen in over 20 years of data,” said Elizabeth Goldman, co-director of Global Forest Watch.

“It’s a global red alert – a collective call to action for every country, every business and every person who cares about a liveable planet. Our economies, our communities, our health – none of it can survive without forests.”

The loss of tropical primary forests – vital ecosystems that store carbon and support biodiversity – amounted to an area nearly the size of Panama vanishing at a rate of 18 football fields per minute.

Globally, fires emitted 4.1 gigatonnes of greenhouse gases, more than four times the emissions from all commercial air travel in 2023.

While wildfires are common in boreal regions, fire has historically been a secondary cause of tropical deforestation. In 2024, however, fires accounted for nearly half of all tropical primary forest loss – up from 20 per cent in previous years. The report attributes the shift to a combination of human activity, rising land pressure and extreme heat, worsened by El Niño and the continued impacts of the climate crisis.

“2024 was the worst year on record for fire-driven forest loss, breaking the record set just last year,” said Peter Potapov, research professor at the University of Maryland and co-director of the GLAD Lab.

“If this trend continues, it could permanently transform critical natural areas and unleash large amounts of carbon, intensifying climate crisis and fuelling even more extreme fires.”

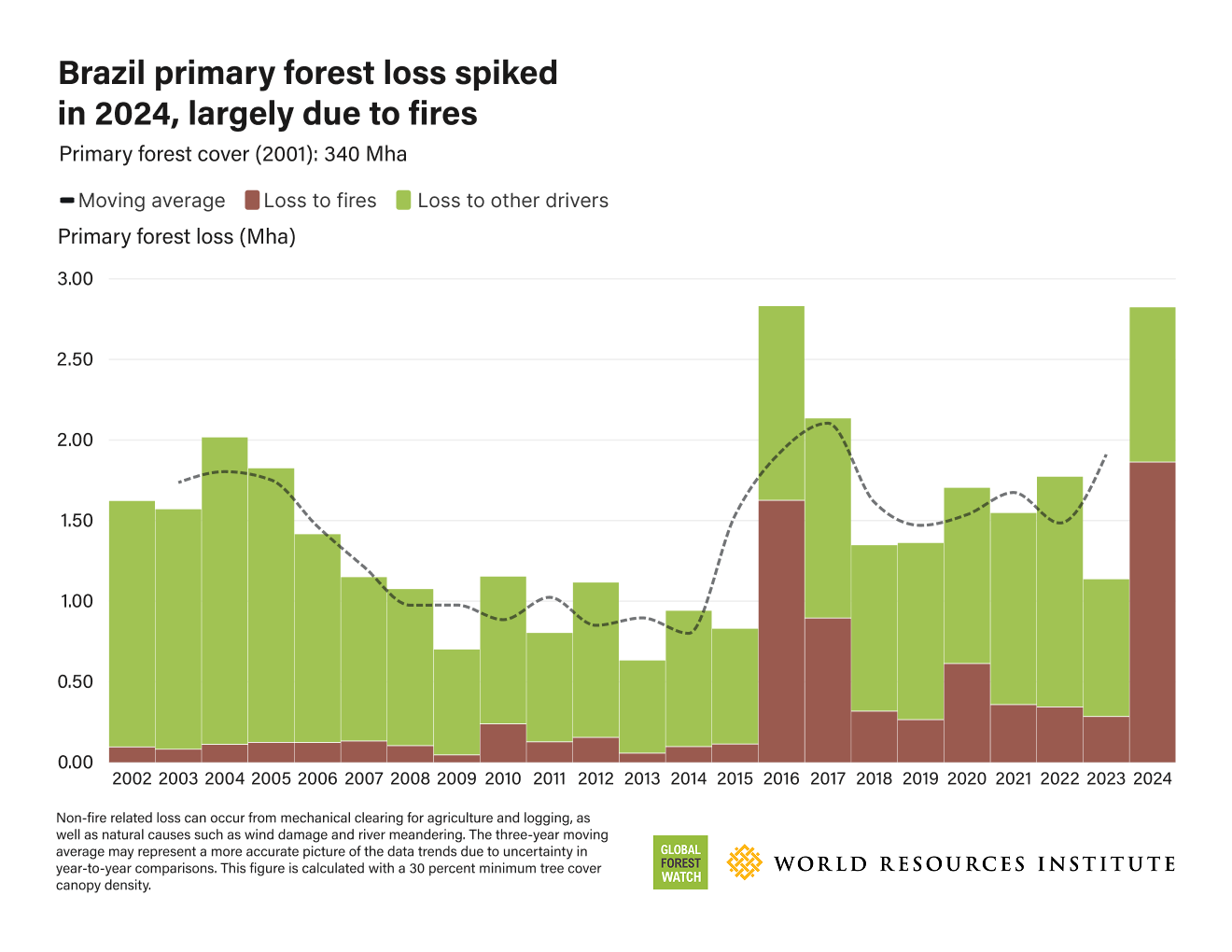

Brazil accounted for 42 per cent of all tropical primary forest loss in 2024. In the Amazon, tree cover loss was the highest since 2016, while the Pantanal saw its worst year on record. Fires, made worse by Brazil’s most severe drought to date, were responsible for two-thirds of the loss in the country – a more than sixfold increase from 2023.

“Brazil has made progress under President Lula (Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva), but the threat to forests remains,” said Mariana Oliveira, director of the Forests and Land Use Program at WRI Brasil.

“Without sustained investment in community fire prevention, stronger state-level enforcement and a focus on sustainable land use, hard-won gains risk being undone. As Brazil prepares to host Cop30 [climate summit], it has a powerful opportunity to put forest protection front and centre on the global stage.”

Bolivia saw the second-highest forest loss in the tropics, overtaking the Democratic Republic of Congo for the first time. Primary forest loss there jumped by 200 per cent in 2024 to 1.5 million hectares, more than half of it driven by fires.

“The fires that tore through Bolivia in 2024 left deep scars – not only on the land but on the people who depend on it,” said Stasiek Czaplicki Cabezas, a Bolivian researcher and data journalist for Revista Nómadas.

“The damage could take centuries to undo.”

Colombia, meanwhile, experienced a nearly 50 per cent increase in forest loss, though largely from illegal mining and coca cultivation rather than fire.

“We need to keep supporting local, nature-based economies – especially in remote areas – and invest in solutions that protect the environment, create jobs and foster peace,” said Joaquin Carrizosa, senior advisor at WRI Colombia.

Forest loss also spiked across Central Africa, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo. In the ROC, fire-related loss rose to 45 per cent, driven by drought and unseasonably hot conditions. In the DRC, longstanding poverty and conflict continue to fuel deforestation.

“There’s no silver bullet,” said Teodyl Nkuintchua, WRI Africa’s Congo Basin strategy and engagement lead.

“But we won’t change the current trajectory until people across the Congo Basin are fully empowered to lead conservation efforts that also support their rural economies.”

Dr Matt Hansen, co-director of the GLAD Lab, warned: “We’re seeing unprecedented forest loss from fire in the few remaining ‘High Forest, Low Deforestation’ countries, like the Republic of Congo. This new dynamic is outside of current policy frameworks or intervention capabilities and will severely test our ability to maintain intact forests within a warming climate.”

Amid the devastation, the report highlighted progress in parts of Southeast Asia. Indonesia reduced primary forest loss by 11 per cent, helped by long-standing efforts to restore degraded land and control fires. Malaysia saw a 13 per cent decline and dropped out of the top 10 for tropical forest loss for the first time.

“We’re proud that Indonesia is one of the few countries in the world to reduce primary forest loss,” said Arief Wijaya, managing director at WRI Indonesia. “But deforestation remains a concern due to plantations, small-scale farming and mining – even within protected areas.”

The year also saw intense fire seasons in boreal forests, with Canada and Russia contributing to a 5 per cent rise in total tree cover loss globally – 30 million hectares in total, an area roughly the size of Italy.

To meet the goal of halting forest loss by 2030, the world needs to cut deforestation by 20 per cent each year starting now. But in 2024, tropical forest loss increased by 80 per cent.

“Countries have repeatedly pledged to halt deforestation and forest degradation,” said Kelly Levin, chief of science, data and systems change at the Bezos Earth Fund.

“Yet the data reveal a stark gap between promises made and progress delivered.”

Rod Taylor, director of forests and nature conservation at WRI, added: “Forest fires and land clearing are driving up emissions, while the climate is already changing faster than forests can adapt. This crisis is pushing countless species to the brink and forcing Indigenous Peoples and local communities from their ancestral lands.”

The report says that the path forward requires stronger fire prevention, deforestation-free supply chains, support for Indigenous land stewardship and greater political will, especially from countries that made bold commitments at climate summits, but are failing to follow through.