The cause of death of two young pterosaurs that had baffled researchers has been revealed by paleontologists in Germany in what they have described as “a post-mortem 150 million years in the making”.

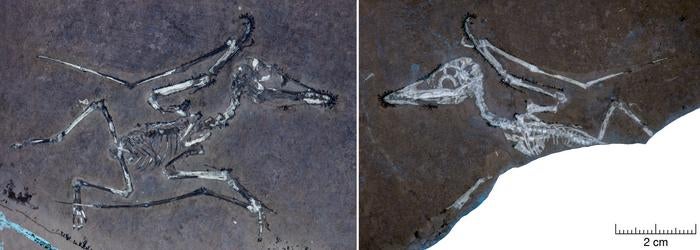

Analysis of the well-preserved fossils of the hatchlings, found in the lagoonal deposits that make up the Solnhofen Limestones of southern Germany, revealed both the flying reptiles sustained similar injuries immediately prior to their deaths – broken wings.

The team, from the University of Leicester’s Centre for Palaeobiology and Biosphere Evolution, said the discovery is powerful evidence of ancient tropical storms and how they shaped the fossil record.

The palaeontologists now believe the pair of young pterosaurs died 150 million years ago when a tropical storm struck what is now Germany, with the high winds breaking their wings.

Both fossils show the same unusual injury, the team said – a clean, slanted fracture to the humerus. Both were “broken in a way that suggests a powerful twisting force, likely the result of powerful gusts of wind rather than a collision with a hard surface”, they said.

“Catastrophically injured, the pterosaurs plunged into the surface of the lagoon, drowning in the storm driven waves and quickly sinking to the seabed where they were rapidly buried by very fine limy muds stirred up by the death storms. This rapid burial allowed for the remarkable preservation seen in their fossils,” the authors said.

The authors said their discovery explains why smaller fossils are so well preserved – they were a direct result of the storms – a common cause of death for pterosaurs that lived in the region.

.jpeg)

Ironically nicknamed Lucky and Lucky II by the researchers, the two hatchlings are believed to have been just days or weeks old when the storm struck.

Lead author of the study Rab Smyth said: “Pterosaurs had incredibly lightweight skeletons. Hollow, thin-walled bones are ideal for flight but terrible for fossilisation. The odds of preserving one are already slim and finding a fossil that tells you how the animal died is even rarer.”

The pair are Pterodactylus, the first pterosaur ever scientifically named. With wingspans of less than 20cm (8 inches) in diameter, these hatchlings are among the smallest of all known pterosaurs. The team said the pair of skeletons are “complete, articulated and virtually unchanged from when they died”.

Several other young pterosaur skeletons have been found in the same lagoonal limestone formation, though without the same injuries as Lucky and Lucky II. “Unable to resist the strength of storms, these young pterosaurs were also flung into the lagoon,” the team said.

Previously it was thought that smaller pterosaurs were the norm for the region, but the research now suggests that larger, stronger individuals were likely able to survive higher winds and therefore didn’t follow the youngsters’ stormy road to death.

When they did eventually die, those around the lagoon likely floated for days or weeks on the now calm surface, occasionally dropping parts of their carcasses into the abyss as they slowly decomposed.

“For centuries, scientists believed that the Solnhofen lagoon ecosystems were dominated by small pterosaurs,” Mr Smyth said. “But we now know this view is deeply biased. Many of these pterosaurs weren’t native to the lagoon at all. Most are inexperienced juveniles that were likely living on nearby islands that were unfortunately caught up in powerful storms.”

Co-author Dr David Unwin, also from the University of Leicester added: “When Rab spotted Lucky we were very excited but realised that it was a one-off. Was it representative in any way? A year later, when Rab noticed Lucky II we knew that it was no longer a freak find but evidence of how these animals were dying.

“Later still, when we had a chance to light-up Lucky II with our UV torches, it literally leapt out of the rock at us, and our hearts stopped. Neither of us will ever forget that moment.”

The research, Fatal accidents in neonatal pterosaurs and selective sampling in the Solnhofen fossil assemblage is published in the journal Current Biology.