Evan Dando, the Nineties grunge heartthrob of The Lemonheads, does not seem to have looked at his life as a tragedy; as a farce, perhaps, because he has never been shy about admitting to his most outlandish disasters – but never a tragedy. For any rock fan, however, it’s hard not to see Dando’s career as one of disappointments.

In the 28 years since Car Button Cloth, the band’s last album for Atlantic, Dando has released just two albums of original music – one solo outing, Baby I’m Bored, in 2003, and the self-titled Lemonheads in 2006. There have been a couple of covers records, but anyone after Dando’s sublime songwriting is out of luck. The reason for this scarcity is simple: making music was an obstacle to his chosen lifestyle, which might well be summed up as taking as many drugs as possible.

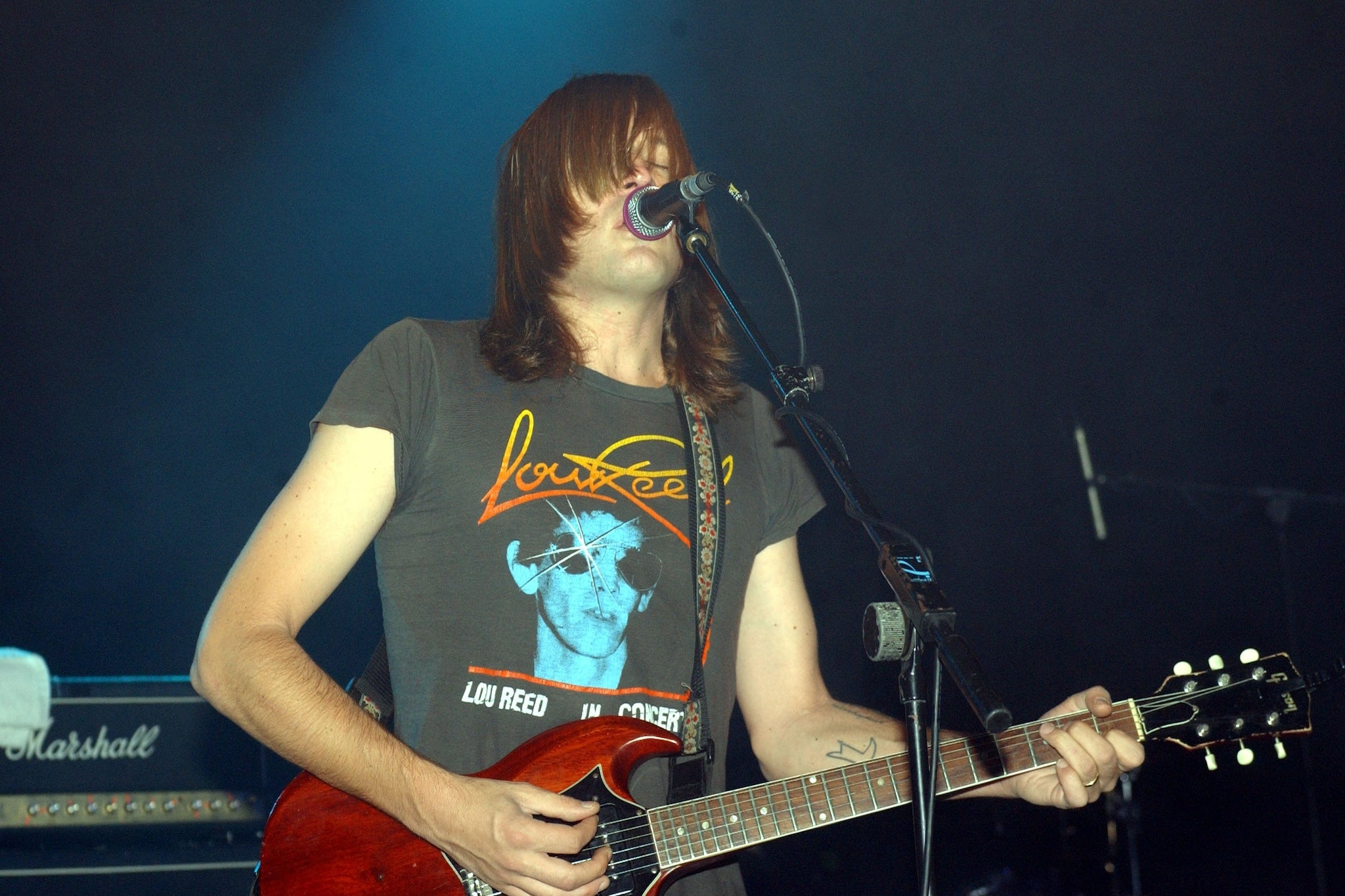

At 57, Dando is two years clean of street drugs, his life saved by moving to Brazil and getting engaged. He tells me this while perched on the steps of a fire escape behind Islington Assembly Hall. But he is unmistakeably a man shaped by using. There is a glint of metal on the right side of his upper jaw, where missing teeth have been replaced, and he speaks in sentences that move between subjects without any apparent reason. Sitting smoking, Dando surrounds himself with objects that may offer comfort – a pile of books, topped by Somerset Maugham’s The Painted Veil, and an old Roland drum machine among them. Later tonight, he will unpack these belongings on stage.

Of his generation of alternative rockers, Dando is arguably the most gifted melodicist. Here is a man capable of composing a seemingly effortless two-minute song that spans nostalgia, introversion, and euphoria. Some songwriters’ entire careers contain less marvel than a single couplet in “Alison’s Starting to Happen” – “She’s the puzzle piece behind the couch/ That makes the sky complete” – ending in a perfectly unresolved chord that hits like, well, a drug.

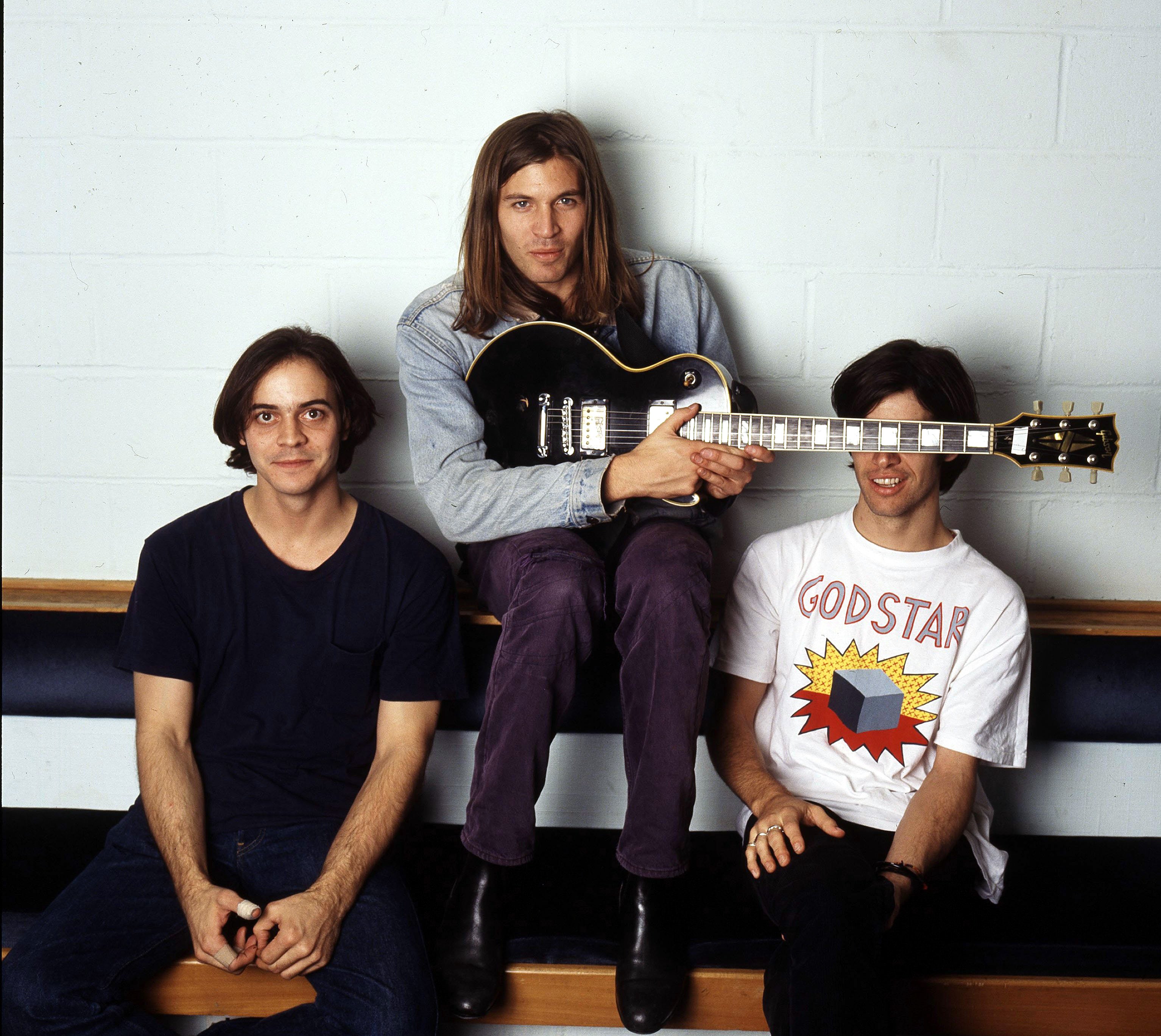

The Lemonheads emerged as a hardcore punk band in Boston in the late Eighties, but after Dando took over he toned down the rage, amped up the melancholy, and scored a string of hits with songs that nodded as much to Gram Parsons as they did to grunge.

With the flawless half-hour of 1992’s It’s a Shame About Ray, and the imperfect but often wonderful Come On Feel The Lemonheads, both more than 30 years old now, Dando became the bronzed, blond pin-up boy of indie: the alterna-hunk of “bubble grunge”. In 1993, he was on the cover of Spin, long-haired and shirtless, kissing Adrienne Shelly. That same year, he made out with Angelina Jolie for the video of hit song “It’s About Time”.

And then he threw it all away, and his subsequent career was one of many fits and few starts as the drugs took over. Today, Dando seems happy and communicative, and given that there have been plenty of interviews in recent years for which he has either failed to turn up or simply refused to speak, this has to count as him being in a very good place.

Dando grew up rich in the suburbs of Boston: his mother was a model; his father a real-estate attorney. He attended a toney school, Commonwealth, where he formed The Lemonheads in 1984 with schoolmates Ben Deily and Jesse Peretz. Though they were initially a band of friends, Dando eased them all out, and by the time of It’s a Shame About Ray, The Lemonheads had become Dando and whomever he fancied playing with – a situation that carries on to this day.

In his teens, Dando was a music snob, swapping out his old Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath records for jazz and classical. “And then I went to see Flipper, and the whole thing changed,” he says. From there, Dando threw himself into Boston’s “f***ing skanky” hardcore punk scene, going to see bands such as SS Decontrol, Gang Green, and Jerry’s Kids.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Sign up

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Sign up

“There was a band called Kilslug who would fill a fire extinguisher with cow’s blood and spray the audience,” he recalls. “We used to play with them all the time when we started. They didn’t like us.” For any particular reason? “I think because there were Jews in our van,” he says. “For real. It’s one of those separate-the-artists-from-the-art situations.”

The Lemonheads signed to the local punk label Taang! and released three albums before jumping ship to Atlantic, by which time Dando had taken control of the band’s direction. Even before that, he was already writing songs more melodically and emotionally expansive than punk required. “We were trying to do what Nirvana was trying to do,” he says. “We didn’t have as good of a dance feel, but all the rest of it was there, the screaming and s***. When Nirvana got big, I was like, ‘Hold on, f*** that. We gotta go the other way. That’s the only way to distinguish ourselves.”

Dando’s songs still had muscle – the crunchy guitars and the pace of punk – but they were coloured by country music. Lyrics were less concerned with existential agony than with everyday cares: the sadness of having to replace a much-loved stove, for example. He sang not of dread, but of memories and wistfulness.

Dando had been using serious drugs since before the band even began. “I was using as much as I could find,” he says. “We had a good coke dealer in our high school.” Any time he scored a part in a school play, he’d buy some coke to celebrate, waiting till he was home to indulge.

Dando says he knew he wanted to try heroin before he even hit puberty; he wanted to be like William Burroughs and Keith Richards. It sounds a little trite from the writer who in the loping, sad ballad “My Drug Buddy” captured in two lines the outlook of the addict: “I’m too much by myself/ I wanna be someone else.”

Surely there must have been some void he was seeking to fill? “I was in a lot of pain about my parents’ divorce,” says Dando, who was 10 when they split. “It was before puberty. I never saw my dad during puberty, and that f***ed me up a little bit, I’d say.” When The Lemonheads got famous, he says, “I tried to get whatever it was I wasn’t getting from my dad from people in general, which was definitely dangerous.” One presumes he means validation, but he doesn’t expand.

When Dando speaks about his family, his answers begin to lose definition, as if he’s caught in a reverie. It becomes hard to follow his train of thought. At one point, he recalls being left alone, aged four, on a beach with his two-year-old sister while his parents went surfing: “I wouldn’t know many parents that would both go out surfing and leave their two- and four-year-old alone.” Later, he talks about his father’s drinking problem; likewise his grandfather’s. One of his grandfathers – the drinker, perhaps, but he doesn’t clarify – was crazy, Dando adds. “He would disappear and be blacked out for two weeks, then turn up in California. I have that, but softer.”

Dando was dependent in other ways, too. He always had to have a girlfriend around to keep him safe. “I would run outside in the night, screaming bloody murder, running away from someone in my dream, in my underwear,” he recalls. “I couldn’t get back into my apartment, so I always had to have a girlfriend [to let me in].” And later, when the band got famous and Dando became the most handsome man in rock, he threw himself into sex.

“When people become pop stars, that’s a really tempting route,” he says now. “I did it to death every night. I’d be in Japan, and be like, ‘Oh, wow! Groupies aren’t extinct here! Cool!’ Fifteen of them would pile in with you, and you’d go, ‘OK, you and you.’ It’s a wild experience. It’s really fun.” Dando adds that he was “always really nice to girls. I didn’t want them to do anything they didn’t want to do. I’d let it happen if it’s gonna happen.”

In the Nineties, as The Lemonheads became more successful, Dando went from leaving it all on the stage to phoning it in, to faxing it in, to sending it in by carrier pigeon. He’d regularly be seen in public completely insensible, utterly without self-control or agency. He was using heroin and crack at the time, yet somehow kept writing songs up until 1996. But other things were more important: “It’s all about waiting for your drug deal. You do that faithfully, and nothing else.”

It’s a measure of how deep in addiction Dando was that this period wasn’t even his rock bottom. That came later, brought on by Oxycontin. “That’s when I got bad,” he says. “And then it was a long sprawl from there to a couple of years ago.” And then Dando says the saddest, most self-defeating thing he could say. He rolls up his sleeve and shows me his arm. “I thought, I gotta have some real track marks before I quit heroin,” he says, with a mordant little laugh. “Junkies think some stupid s***.” He was so often said to have died that his forthcoming memoir is called Rumours of My Demise.

For decades he used heavily. There were periods without – I spoke to him in 2017 and he said he was clean, and sounded engaged – but they never lasted. Three years ago he appeared to reach a nadir. Dando, the songwriter who’d sold millions of records, was appealing on Twitter for donations. On Cameo, he was offering recorded performances for cash. He had, he says, quit heroin by that point, but was still using cocaine: “I was f***ed up still.”

When The Lemonheads were offered $170,000 to tour with the punk-rock band Jawbreaker, their management accepted. Dando, though, believes they were mismatched. “We weren’t supposed to tour together,” he says now, with an air of wounded pride. “This was us supporting them, and f*** that s***. They were losers. I went up to the singer, and I said, ‘Are you the singer of that p***y-ass band Jawbreaker?’ That’s all I had to do to get sacked from the tour.”

It’s worth noting that this isn’t exactly an agreed-upon story – at the time, Dando said he was penalised for breaking Covid regulations, and he slung his insults on social media. Regardless, he still needed the $170,000, so he did some crowdfunding on Twitter in the hope that someone would send him some money.

A few hours later, Dando gets on stage at Islington Assembly Hall, alone with an acoustic guitar and his comfort objects, and this time he isn’t phoning it in. His voice has suffered from the drugs – it’s still wounded and sad, though thinner and quieter than it once was – but he is completely committed, playing for far longer than scheduled, until his tour manager has to unplug him to avoid breaking the curfew.

“I play for my own satisfaction and sense of self-worth,” he says, “because I don’t do anything else, really. I paint, but that doesn’t give me any self-worth because I’m not good at it yet. I really love fishing, but the thing that really keeps me going is going on tour, because it gives me something to do every day.”

It seems that Dando’s version of clean is not quite the same as a drug tester’s. He eulogises the Polish LSD he tried in Brazil (“I think acid is OK once in a blue moon”) and admits to “scamming” doctors to get ADHD medications (when I ask, after a particularly convoluted answer of his, if he has ever been diagnosed with the disorder. He hasn’t.)

It’s hard not to warm to Dando. His clothes are dirty, and he has a pot belly now; those blond locks are unbrushed and sticking out at odd angles. He looks like neither a rock star nor a heartthrob. But he is warm and charming; engaged and engaging. And best of all, he’s nearly finished a new Lemonheads album, called Love Chant. “It’s really psychedelic and heavy and then quiet, and it’s all originals,” he says. Now, at last, he’s fallen for music again. “I know that I’m a good person, and whatever’s going to happen to me is OK,” he says. “I’m, like, really chill.”

Evan Dando’s memoir, ‘Rumours of My Demise’, is scheduled for release on 1 May 2025