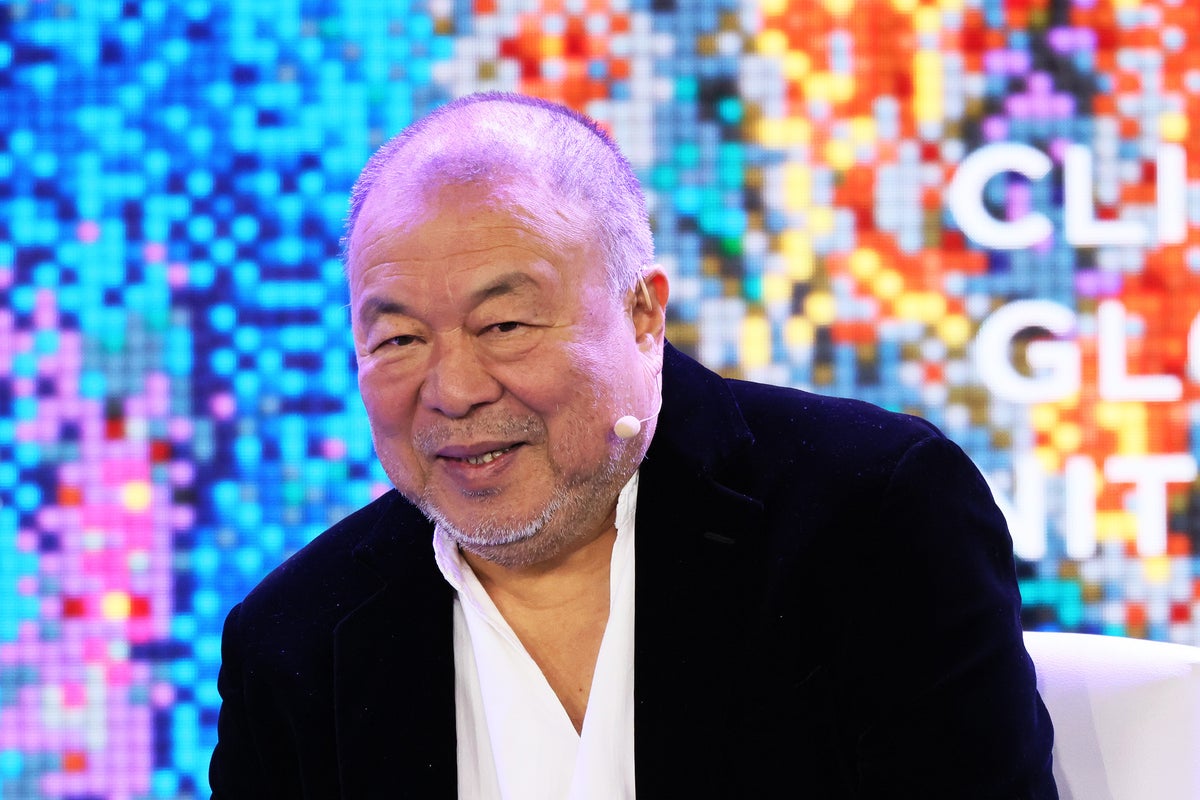

Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei has spoken about the experience of quietly returning to his homeland for the first time in about a decade, describing it as akin to a “phone call that had been disconnected for 10 years suddenly reconnecting”.

The three-week visit in December was Ai’s first since 2015, when Chinese authorities returned his passport. It had been confiscated nearly four years earlier on tax evasion charges, which had also seen him land in detention for 81 days.

He lived under police surveillance after his release, with phone and internet use strictly monitored, before he moved to Berlin. He spent the next decade living in Germany, the UK and Portugal.

During his visit, Ai shared pictures and videos on social media of personal moments in Beijing as he travelled with his teenaged son and reunited with his 93-year-old mother.

Ai told CNN he didn’t need to take any particular precautions for his visit, although he was “inspected and interrogated” for almost two hours at the airport in Beijing.

“The questions were very simple. How long do you plan to stay here? Where else do you plan to go?” he told the American media outlet, adding the rest of his time in the country was “smooth and, one could say, pleasant”.

Asked whether this suggested a change in the attitude of Chinese authorities towards him, Ai said that he didn’t believe there was a recent shift, and was instead a reflection of his longtime views.

“Although a country or group may disagree with my positions, they at least recognise that I speak sincerely and not for personal gain,” he said.

He described the experience of returning as emotionally significant, especially after 10 years away.

“What I missed most was speaking Chinese,” he said. “For immigrants, the greatest loss is not wealth, loneliness or an unfamiliar lifestyle, but the loss of linguistic exchange.”

Ai’s conflict with the Chinese authorities arose from a series of direct challenges to official narratives. After the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, he launched an investigation into the collapse of school buildings and published the names of over 5,000 children who had died, accusing officials of corruption and cover-up over shoddy construction.

“The kind of authoritarian state we have in China cannot survive if it answers questions – if the truth is revealed, they are finished. So they started to think of me as the most dangerous person in China. That made me become an artist, but also an activist,” he wrote in a 2018 opinion piece for The Guardian.

From exile, Ai continued to make politically engaged work, including the 2020 documentary Coronation, which examined China’s handling of the Covid outbreak, and Cockroach, which focused on the 2019 Hong Kong protests.

He had previously made Human Flow, a film on the global refugee crisis that took him to nearly 20 countries. His 2016 installation Laundromat used clothing left behind by refugees to evoke displacement and loss.

In 2023, the artist had said he would return to China if “they don’t take my personal freedom away, if I can express myself freely, and if they do not put me in jail secretly again”.

“It’s just about the very basic principles of surviving, so I cannot,” Ai said at a London exhibition in April 2023.

In an interview with The Independent last year, Ai talked about the double standards in the West’s “so-called democracies”.

“You cannot talk about human rights in Russia or China and then apply different rights in the Middle East,” he said. “You’re just using too many double or triple standards. The West has totally lost the moral high ground.”