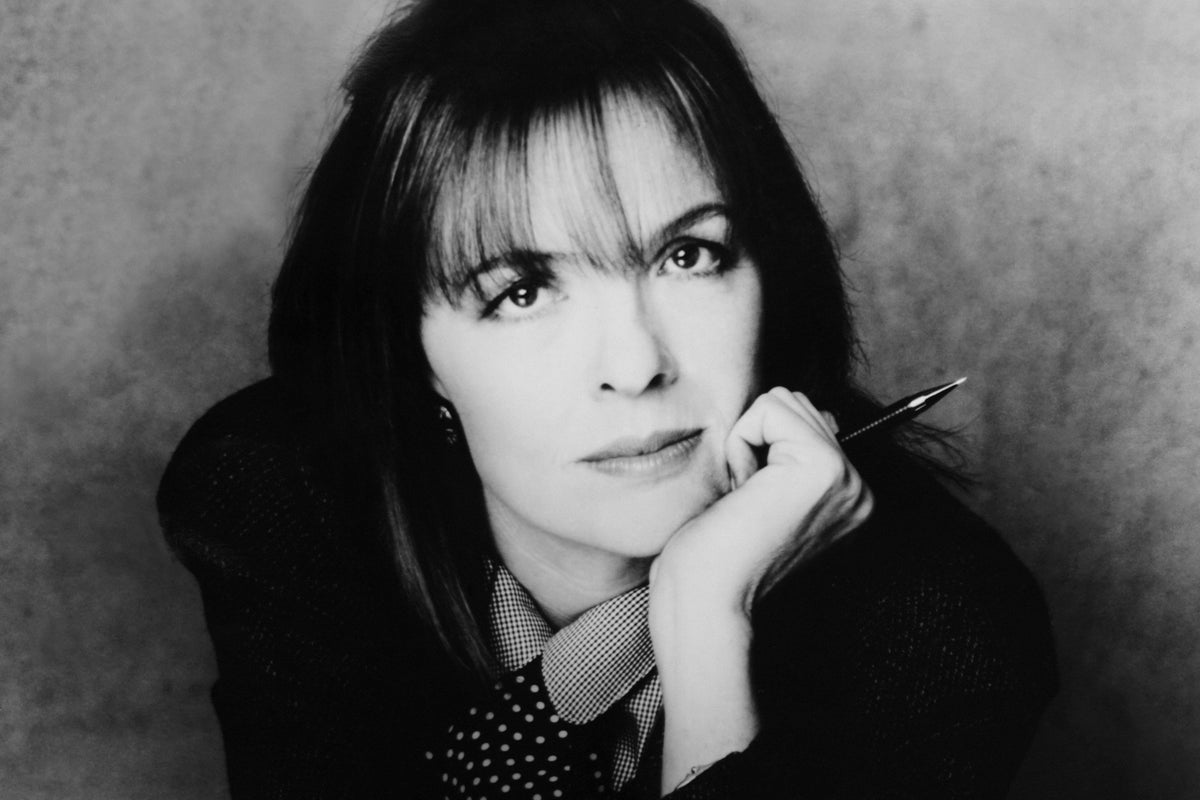

In 1987, Diane Keaton directed a documentary about dying. Heaven is a scrapbook collage of a film, in which Keaton intercuts footage of Hollywood stars, silent movies, dead clowns, and floating heads alongside interviews with individuals of all stripes: she asks them what they believe happens in the afterlife, what lies beyond this mortal coil, and whether they’ll be happy once they get there. She couldn’t believe the film got financed. “It turns out that the people who like Heaven most are from two groups: women and ‘experiential’ types,” she told Interview magazine that year. “I asked, ‘What’s an experiential type?’, and it turns out that they’re your weirdos, oddballs – your downtown set.”

Keaton, who has died at the age of 79, had a life full of these eccentric little detours. It’d be wrong to call her underrated. The outpouring of love from co-stars, exes and movie fans in the hours since the news broke is proof of how much she mattered – as an icon of New Hollywood filmmaking, a symbol of off-kilter style and off-kilter living, and a pioneer in how we think about comedy, romance and performance on screen. But there was always a sense that few got the totality of her, that she had unusual interests and a singular point of view on the world that went beyond the androgynous dressing for which she was known, or that anxious, fiddly la-di-da, la-di-da, la la of her voice.

Keaton produced independent films about school shootings, published coffee table books of her photography, had an interest in taking snapshots of shopfronts and houses, and wrote elegantly and frankly about mental illness in a book about her late brother, who struggled throughout his life.

In interviews, particularly those that took place in her later years, Keaton breezed past many of these things – as if they were mere spill-over from a big box of zany personal quirks that no one could possibly be interested in. “I really am fascinated by these [abandoned] places, because they’re abandoned, but they were something very important,” she told The Guardian in 2023. “Anyway, we shouldn’t talk about that, because people are gonna go: ‘What is she talking about? Get rid of her!’” It was always unclear if this sort of approach to public conversation was defensive by design, or whether she truly believed people wanted the “Diane Keaton persona” over the real nitty-gritty of her.

That persona, of course, was gargantuan. The scatterbrained nervousness. The sing-song neuroses. The menswear. Woody Allen helped harness it, directing her to an Oscar in his seminal romcom Annie Hall (1977), but it got massaged over time – in the squawking comic hopelessness of her businesswoman-turned-single-mum in Baby Boom (1987), the slapstick delusion she brought to the scorned ex comedy The First Wives Club (1996), and the weeping messiness of her work in Nancy Meyers’s late-in-life romcom Something’s Gotta Give (2003).

I liked her sadness most of all, though. There is the sheer devastation slapped across her face in the final seconds of The Godfather (1972), of course, and the haunted unease of her work in Looking for Mr Goodbar (1977), in which her character trawls Manhattan’s singles bars aching for sex and attention and hurtling towards certain doom. But it’s also there in so many of her comedies. Annie Hall hinges on a particular kind of self-loathing typically masked by comic theatrics and flibbertigibbet filler words. Annie is convinced she’s not smart or interesting or beautiful (Allen based the character on Keaton herself), despite very clearly being absolutely all of these things.

Later on, in 1993’s Manhattan Murder Mystery, arguably Allen’s most underrated work, he cast Keaton as a middle-aged melancholic, somebody suddenly bored by her life and marriage, pining after what might have been (in the form of a man she could have run off with), and recasting herself as an amateur detective to give her something novel to do. It’s an incredibly funny performance, but laced with prickly anxiety. I think often of a scene in which she and Alan Alda, playing the one who got away, stake out a woman’s apartment in the rain, and talk about a time when they could have gone all the way together. “It could have been our little secret,” Alda tells her. “Yeah. God,” she replies. “It feels like such a long time ago, doesn’t it?” She trails off, sad and blushing.

Call it the curse of the romantic comedy heroine that Hollywood’s greatest purveyors of quiet insecurity and restlessness (among them Meg Ryan, Sandra Bullock, and Lisa Kudrow) are so often considered far breezier and less complex actors than they actually are. Keaton is very much the blueprint for this: a woman of such depth and fascination, yet so often reduced to a “type”. Her later work saw her play variations on the klutzy, chaotic, immaculately tailored neurotic: Book Club, Summer Camp, Arthur’s Whisky, all movies that felt wildly beneath her.

In death, hopefully, the scope of Keaton’s work and interests will be more widely appreciated. The memoirs. The photographs. The episode of Twin Peaks she directed. The fact that she was, genuinely, always a Hollywood outsider – an inspiration for many, beloved by many more, but someone who only ever marched to the beat of her own drum. “I had no sense of the world and I did not hang out,” she told Interview back in 1987, about her time in the outré musical Hair in the late Sixties. “I was never a true member of the tribe, although I did like the show.”