Vibha Chawla never paid much attention to air pollution. But when her elderly mother almost died of a severe coughing fit during the Diwali holidays late last year, she decided to act.

Chawla, a 50-year-old resident of Delhi’s affluent Siri Fort area, barged into a meeting where the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was preparing its manifesto for the upcoming election in the capital, where she says she was one of the few voices to raise the issue of air pollution.

“I stood up and said, ‘We’re choking here and no one is talking about it’. Some people nodded, but I could tell most just didn’t care,” she tells The Independent.

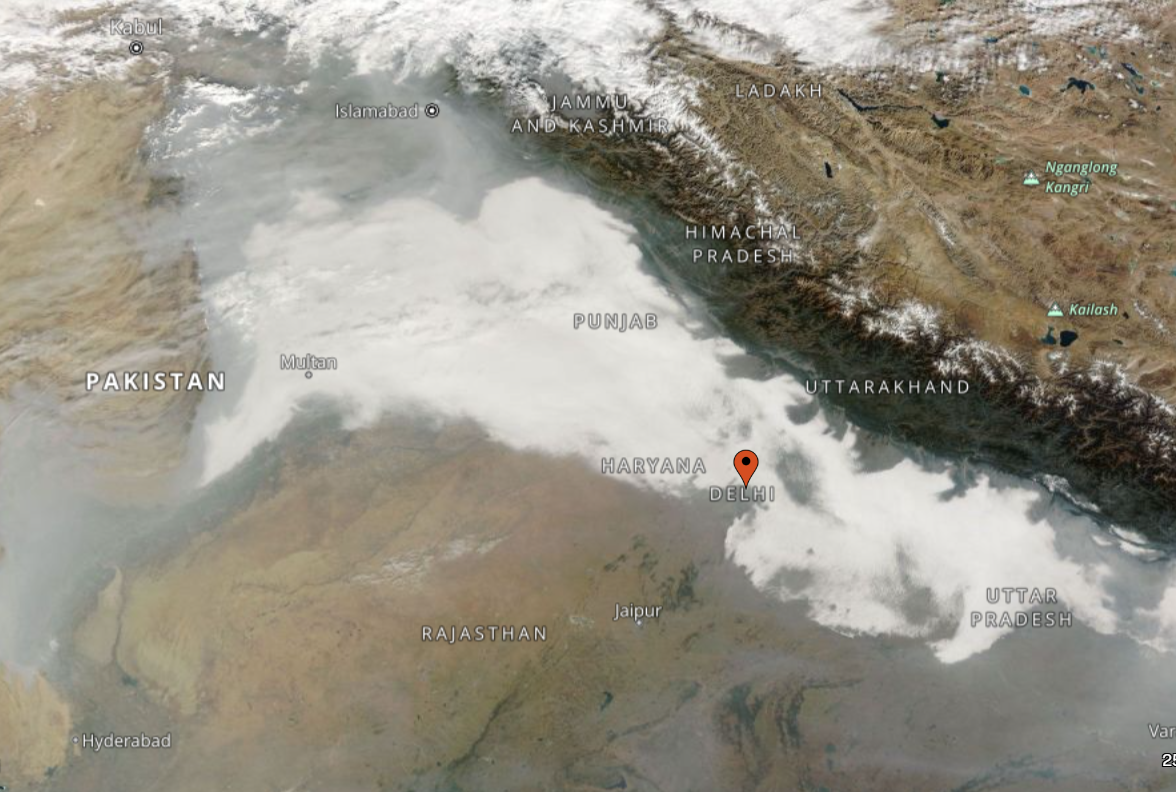

Chawla, wasn’t surprised – although much of northern India remains blanketed in a toxic haze for months every year, pollution has rarely been a major issue in elections in India. But with Delhi going to the polls for important state assembly elections on 5 February, things are changing, and air pollution is finally finding its way into political debates and manifestos. Politicians going door-to-door to ask for votes are being forced to answer questions about the toxic air that continues to surround the city.

But the solutions they are promising, experts say, barely scratch the surface of the problem.

The city, home to some 33 million people, has long struggled with hazardous air. The air quality index this winter repeatedly rose above 1,000, more than 15 times the level considered safe by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Yet public discourse around pollution has been overshadowed by issues like water and power shortages and corruption. In recent weeks, however, faced with mounting public pressure and undeniable health impacts, politicians have been forced to talk about it.

The BJP, which rules the country and the neighbouring states of Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, has placed pollution at the centre of its Delhi campaign to take on the Aam Aadmi Party, or AAP, which governs the capital. The latest opinion polls show AAP retaining control of the capital with the narrowest of majorities, closely followed by the BJP in second.

“People are falling ill due to worsening air quality. We cannot let the AAP government go scot-free,” the BJP’s Delhi chief, Virendra Sachdeva, declared during the launch of the party’s manifesto in November.

The Congress party, once a dominant force in Delhi politics but now polling a distant third, has also seized on the issue of pollution to target AAP. Senior party member Sandeep Dikshit addressed a press conference on Saturday where he outlined how Arvind Kejriwal’s government had failed to act.

“The issue of pollution really hit me during our door-to-door outreach. Common people, even those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, are questioning us about how their health is being impacted by polluted air and water. They know this isn’t just a seasonal problem anymore,” the former parliamentarian said.

“The people are no longer willing to accept excuses. They want accountability, and they’re asking tough questions.”

Experts say the issue has come into focus because it can no longer be ignored but all political parties are guilty of downplaying the crisis in the past.

“Air pollution has become a political issue, mostly because people, organisations, citizens groups, mothers have organised. And elections are happening at a time when air quality is really bad, so it’s visible,” says Shweta Narayan, a global climate and health campaigner at the organisation Health Care Without Harm.

She points out that many politicians across party lines have made statements in the parliament to deny the link between air quality and health.

“Everybody in the political arena has been dismissing the concerns about pollution,” Narayan says. “So to now promise action feels a little disingenuous and it seems like they’re exploiting the moment for political gains.”

While Delhi’s pollution often gets blamed on farmers burning crop stubble in Punjab and Haryana, it is vehicular pollution that is at the forefront of the election campaign. Vehicular emissions are the single largest contributor to the capital’s toxic air, accounting for 51.5 per cent of locally generated pollution, according to the Centre for Science and Environment.

The BJP has promised to add more electric vehicles, especially buses, and create more walkable paths.

Dikshit of the Congress party accused AAP of failing to expand public transport, which he cited as a key reason for rising pollution.

Despite a 1998 Supreme Court directive mandating a public bus fleet of 10,000, Delhi currently has only 7,683 buses, including 1,970 electric buses, falling well short of the benchmark of 60 buses per 100,000 people.

Public transport challenges extend beyond buses. The Delhi Metro, which has a network of 351km, has not regained pre-pandemic ridership levels.

A 2024 analysis by the Centre for Science and Environment shows private vehicles, including two-wheelers, cost significantly less per kilometre than public transport, further discouraging people from switching.

“If these surplus 2-2.5 million people are opting for private vehicles, it’s clearly adding to Delhi’s vehicular pollution,” Dikshit says.

AAP has defended its record, pointing to measures like the introduction of over 1,900 electric buses to the city’s fleet. “In 2016, there were only 109 days out of 365 when Delhi’s air was clean. This year we achieved clean air for 209 days. We’ve done 70-80 per cent of the work, and the remaining will be done in the third term,” state environment minister Gopal Rai said in an interview with ETV Bharat.

In the past, AAP has installed smog-cleaning towers and proposed cloud seeding but critics have described such measures as “band aids” and not solutions.

“Air pollution management is a highly scientific process that requires the highest level of political will. Both the central and Delhi governments have had opportunities to show results, but neither has done anything worthy of praise,” Aarti Khosla, director of Climate Trends, tells The Independent.

Criticising the National Clean Air Programme, Khosla points out that it focuses on reducing pollution by larger PM10 particles instead of the more harmful PM2.5. “This approach is like putting a bandaid on a bullet wound,” she says.

Delhi’s people are also frustrated by extreme pollution control measures that go into effect every November, including fines for diesel and petrol vehicles and closures of schools.

“Every year, the same drama happens. Schools shut down, construction is banned and odd-even vehicle schemes are announced. But what’s actually changing?” Chawla asked.

Many of these ad hoc measures target ordinary citizens while violations by more powerful interests go unnoticed, activists say.

Illegal construction and tree felling continue unabated, for example, even when restrictions are supposed to be in place.

Chawla recounts how construction dust aggravated her mother’s condition. “We complained to the Residents’ Welfare Association and even police, but nothing happened. It’s like the rules only apply to the poor,” she says.

Bhavreen Kandhari, a green activist, says the government’s data on the city’s green cover is misleading. “They include shrubs and green spaces, not just trees. Meanwhile, five trees are cut every hour in Delhi with permission, and who knows how many are cut illegally?”

Kandhari accuses politicians of focusing on “optics” to show people they are doing something instead of actually addressing major violations.

It is in this context that the BJP’s campaign promises are under scrutiny. Critics note that the party governs Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, which contribute significantly to pollution in Delhi through stubble burning and industrial emissions. In Punjab, where AAP is in power, farm fires remain a persistent problem despite promises over the years to address it.

Ashwani Khurana, a Delhi businessman who has spent a fortune on air purifiers for his home and cars, does not think the election will make much of a difference when it comes to tackling the problem of pollution.

He is instead pinning his hopes on increasing awareness to bring change.

“We are quick to blame politicians, but are we doing our part? Every shopkeeper burns garbage outside their shop, adding to the pollution,” he tells The Independent.

For Chawla, however, this election feels different.

“We’re finally talking about it,” she says. “Maybe this time, they can’t ignore it anymore.”