It rarely takes more than a few scrolls to see an AI-generated video in 2026.

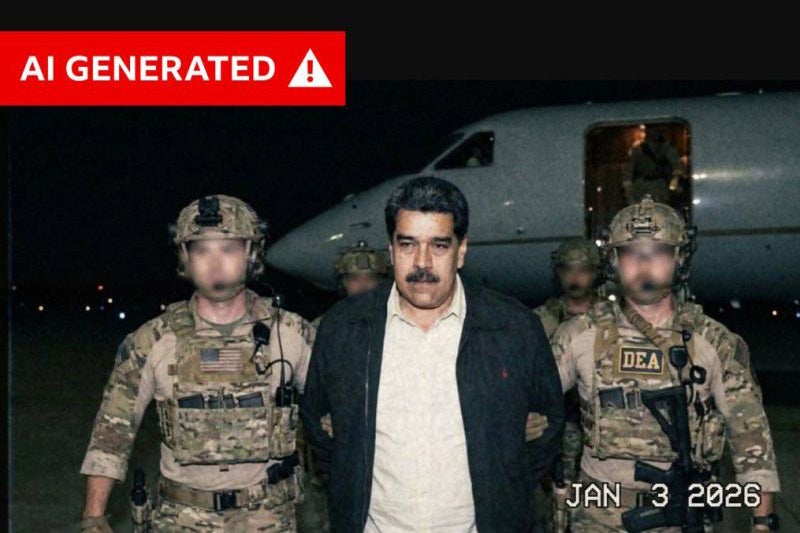

From the capture of Nicolas Maduro by US forces in Venezuela to the fatal shooting of members of the public in Minneapolis by ICE agents, millions of people are consuming AI-generated videos and images on some of the world’s most significant news events – making it impossible to discern what is real or fake.

Experts have warned The Independent that AI-generated content is spreading at such a rapid pace that it is filling the information void before facts emerge, leading to the emergence of false narratives as news organisations scramble to verify details.

“As AI videos continue to improve, it’s becoming harder to trust what we see while scrolling through social media,”, says Sofia Rubinson, senior editor at Newsguard’s Reality Check.

“Visual cues that once helped us spot fake content are no longer reliable, increasing the risk of misinformation spreading at scale — especially when AI fakes are amplified by well-known or verified accounts.”

In such an unregulated information space, bad-faith political actors can now claim that real videos are fake.

“What we now see is a real video will start circulating and they will claim it’s an AI deepfake, which gives them plausible deniability,” warns Professor Alan Jagolinzer, co-chair of the Cambridge Disinformation Summit.

“That’s actually part of the danger here, and arguably it’s more insidious than people buying into a fake video.”

Even the White House recently provoked outrage after sharing a digitally altered photo of an activist who was arrested for organising an anti-ICE protest at a Minnesota church. The picture had been edited to make it look like she was crying.

Analysis by digital forensics expert Hany Farid, a professor at the University of California Berkeley, said the image was likely edited with AI.

“This is not the first time that the White House has shared AI-manipulated or AI-generated content. This trend is troubling on several levels. Not only are they sharing deceptive content, they are making it increasingly more difficult for the public to trust anything they share with us,” Farid told CBS News.

Asked whether other image-editing software had been used, the Trump administration directed The Independent to a tweet from Kaelan Dorr, the White House deputy communications director. It simply said: “The memes will continue. Thank you for your attention to this matter.”

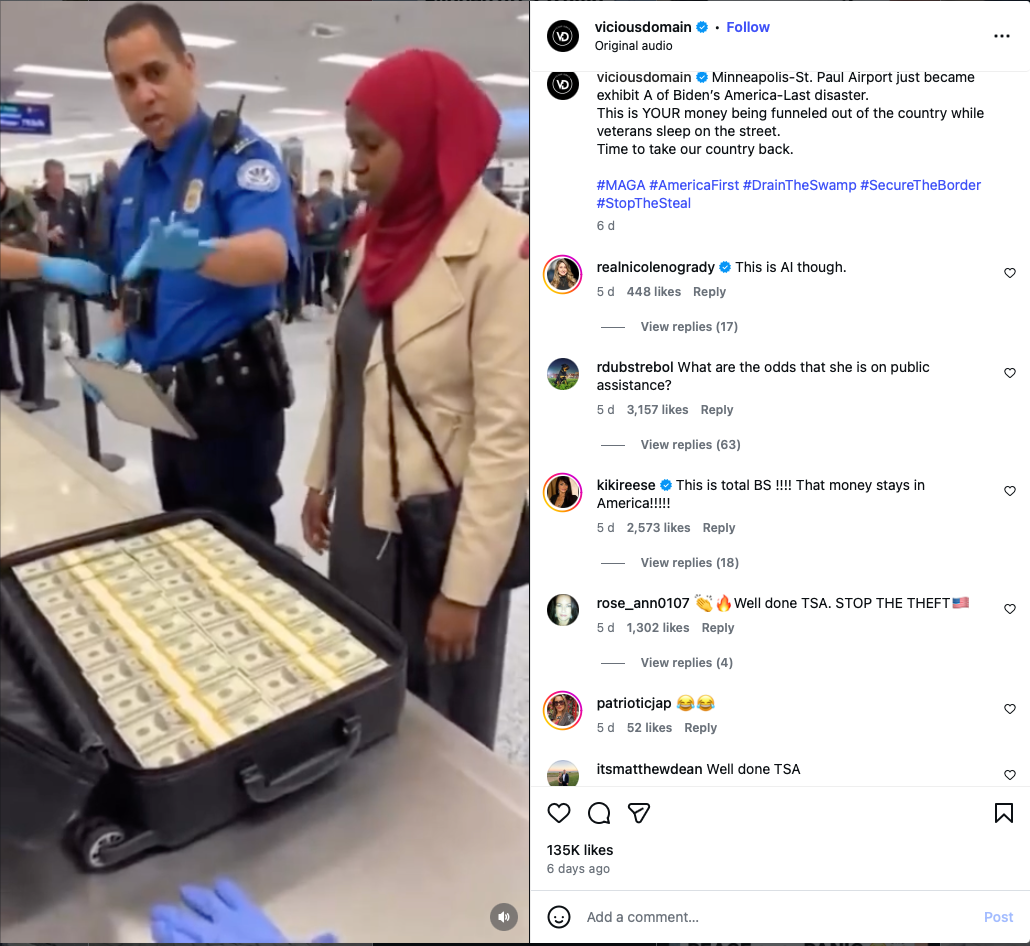

Another video generated by AI purported to show a Somali woman caught at Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport attempting to smuggle $800,000 of welfare support cash out of the country. The video, viewed by millions of people across multiple platforms, appeared to reference allegations that Minnesota’s Somali community participated in wide-scale social services fraud, which prompted ICE agents to swarm the state.

Footage appears to show a woman in a headscarf looking outraged in front of a suitcase full of neatly arranged cash. “You have no right! That’s my property, all of it,” she yells while airport security replies: “I know my rights.”

Jeremy Carrasco, a media consultant specialising in AI media literacy, told The Independent that he was “95 per cent sure” that the clip was generated using OpenAI’s Sora 2, without a watermark. The main giveaway for him was the suitcase.

“This looks like a briefcase size. This doesn’t look like any luggage size that we would have in the United States,” he said, adding that it had an unusually large shell. “If she was walking with this, the cash would have just like shaken around because there would have been too much space in the suitcase.”

Comments underneath the video were flooded with people agreeing with the actions of the officers, such as: “Well done TSA. STOP THE THEFT”.

The Independent has contacted Meta for comment about the post.

Check the source

Outside the US, content generated by AI has also played a role in promoting false narratives about major global incidents including the arrest of Maduro, protests in Iran and the recent antisemitic terror attack on Bondi Beach.

According to Mr Carrasco, the biggest step people can take to discern the from the fake is a simple one. Ask yourself: do I trust this source?

“If you don’t trust the source or you’ve made a judgment that you can’t, move on with your day,” he says. “There are a lot of indications. For example, a page that just reposts a ton of different crap from everywhere isn’t going to be able to discern if they’re reposting an AI video or a real video either.

“You need to look at the original source or consume this through a news organisation that is accredited and has an authentication department. Just make sure that they’ve ruled out that it isn’t a real video that’s been modified.”

Trying to find an original source can also allow you to get the best quality of media, Mr Carrasco explains. Videos that get reposted or re-uploaded can get re-upscaled by a machine learning algorithm that is trying to make them higher definition, which can mean that perfectly legitimate videos can end up with a lot of the same qualities as an AI-generated video.

Look at the background

While AI-generated images can appear quite convincing in the foreground, Mr Carrasco says that the background is “oftentimes where a lot of the bodies are buried.”

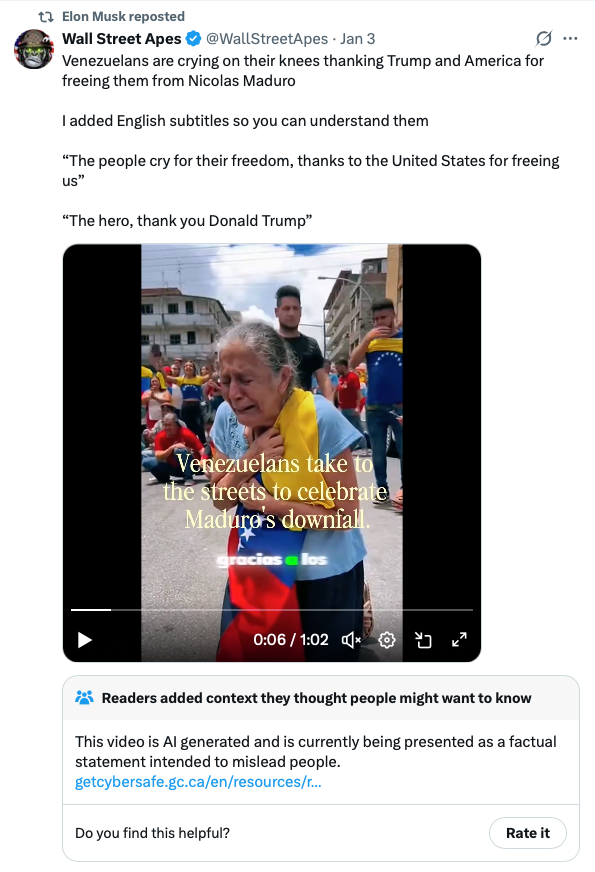

Mr Carrasco highlights a debunked AI generated video that claims to show Venezuelans crying in celebration of the arrest of Maduro.

“I think anyone can see that the guy at the back is actually holding a flag at first and then after it goes behind her head he is no longer holding the flag.”

After looking at the edges of the frames in AI-generated videos, you can find things coming into scene that don’t quite make sense. These include hands or changing facial features.

Dealing with the impact of AI generated content and its impact on politics and society will take “patience and evidence”, experts say. But we can also ourselves by asking some basic critical thinking questions.

“Try to assess, not just the message, but the incentives behind the message. So who is communicating and what are they getting after?,” says Professor Jagolinzer.

“What’s in it for them to send that message out? I think people forget that when we communicate, we have incentives, we have a reason to communicate. So I try to get people to think about ‘why are they telling me this? what’s in it for them?’”

The scale of false information is “worse than anything we’ve seen before” because of how easily accessible generative AI apps are, Mr Carrasco said.

“It’s not only a question about how we detect individual things, but also about how society is processing this new wave, this flood of fake images and fake videos that they’re seeing every day.”