In the late 1980s, after the US-backed Pinochet regime had destabilized their country, José* and Claudia* moved from Chile to California with their two young daughters. Alejandra*, the oldest, was five years old; Ines* was still an infant, about to turn one. Their mother still has her old Chilean passport with the three-person photo they took for the journey, Alejandra and Ines grinning together in their mother’s arms. Back then, minors routinely traveled on their mother’s passport.

Alejandra and Ines are long grown now, both in their mid-30s. José and Claudia are both 65 years old. And instead of doing what they always imagined they’d be doing — celebrating their naturalization, retiring comfortably after working and paying taxes diligently, getting to know their daughters’ new families — they are planning a very different life. They are packing up almost 40 years’ worth of belongings, keeping an eye on the neighborhood apps that let them know when ICE is in the area, and holding clandestine meetings with an immigration lawyer about how to self-deport safely. After spending almost their entire adult lives in America, José and Claudia plan to kiss their daughter goodbye outside their rented family home and get on a plane at LAX in the next few weeks. They know they will never be allowed to return.

“The thing is, we were for so many years over here paying taxes,” says José. “And working hard, working so hard… We pay, pay, pay, and we receive nothing back. And the worst thing is [Claudia] got sick, and I got sick.”

Undocumented immigrants across the US have long paid taxes, even without legal immigration status. Since 1989, the IRS has allowed people without Social Security numbers to pay income taxes by using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN). This system was created so anyone earning money in the country could meet their tax obligations, regardless of immigration status. Many undocumented workers also have taxes withheld automatically from their paychecks by employers, meaning they contribute to federal programs like Social Security and Medicare even though they are not eligible to collect those benefits. This means that undocumented people have been steadily contributing to America’s tax base for decades — an estimated $96.7 billion in 2022 (the latest year on record) alone, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. That includes well over $8 billion in the state of California, where José and Claudia have always lived.

Although their life in California wasn’t as hard as their situation in Chile — where tens of thousands of socialists were murdered under the fascist dictatorship, and unemployment had reached almost 30% — it was still a tough life for José, Claudia and their two young children. Ines remembers their initial apartment in the Coachella Valley with fondness: “We had a lot of community back then,” she says. “Our neighbors were our friends, like in the apartment complex, and everyone was Latino. There were Chileans, Peruvians, Mexicans, a lot of Cubans. Growing up, there were just so many immigrants around us, actually.” They had a supportive community but it was very different from Chile. José and Claudia struggled to adapt to the desert environment, where summer temperatures regularly topped out at 120F (“I mean, Chile is a cold country!” says José.) And they learned English slower than their children, who became fluent once they went to school.

While Ines and Alejandra progressed through elementary, middle and high school, José worked installing water filtration systems and Claudia waited tables in restaurants. And slowly, the immigration laws changed for the worse. First to go, in 1993 under the Clinton presidency, was the ability for undocumented immigrants to hold full and unrestricted drivers’ licenses. That meant that although José and Claudia could keep renewing the licenses they’d applied for under the Reagan administration, their children wouldn’t have the same privileges.

“I think it was really hard for me and my sister when we were teens, and we realized that there was a lot we couldn’t do,” says Ines. “Our school would be going on a trip and we’d be like: Oh, we can’t do that. Or I’d want to get a driver’s license and I can’t at 16… And they’re these really big markers of liberation when you’re young, of being like, ‘I’m gonna drive!’ or ‘I’m gonna get on a plane for the first time!’ And we were like: Oh, we can’t do those things.”

Where they lived was a seasonal town, and their mom’s wages especially were dependent on tourists. Six to eight months of the year, the family would be doing OK. And then finances would suddenly drop, and there was no safety net. At one point, when Ines was in high school, the family had to move into a small house with “a bunch of other immigrants”. She remembers there being 10 people in a tiny, cramped space, living almost on top of each other.

“We had a lot of curiosity, both my sister and I, about where we were from,” Ines adds. “We wanted to understand and feel a part of the place that we were born in.” But they couldn’t travel back to Chile: “Going back meant that we could never come back to the States. And we knew that.” Indeed, any international travel at all was off the cards. For Ines especially, who entered the US as a baby and had no memories of anywhere else, the idea that she could be barred from America felt both terrifying and absurd. So she accepted that she’d have to stay put.

Both José and Claudia have medical conditions that require daily medication: José has diabetes and Claudia has rheumatoid arthritis. They’ve spent the past few years self-funding their healthcare through Obamacare, but now they’ve turned 65, they’ve aged out. American citizens in their situation would start Medicare (or the California equivalent, Medi-Cal.) But, because they’re undocumented, they don’t qualify. They’ve paid taxes toward the system all their lives, but they won’t be able to access it themselves. And paying out-of-pocket medical expenses simply isn’t sustainable.

As the end of the Biden presidency approached, Ines hustled to get her green card and citizenship sorted as soon as possible. She’d just married an American citizen — and she’d entered the US as a child, making her a DACA recipient or “Dreamer” — so she still had an easy route. It was still expensive and time-consuming, and drained her paltry savings. But she did it, with the hope that she’d be able to sponsor her parents to become citizens not long after.

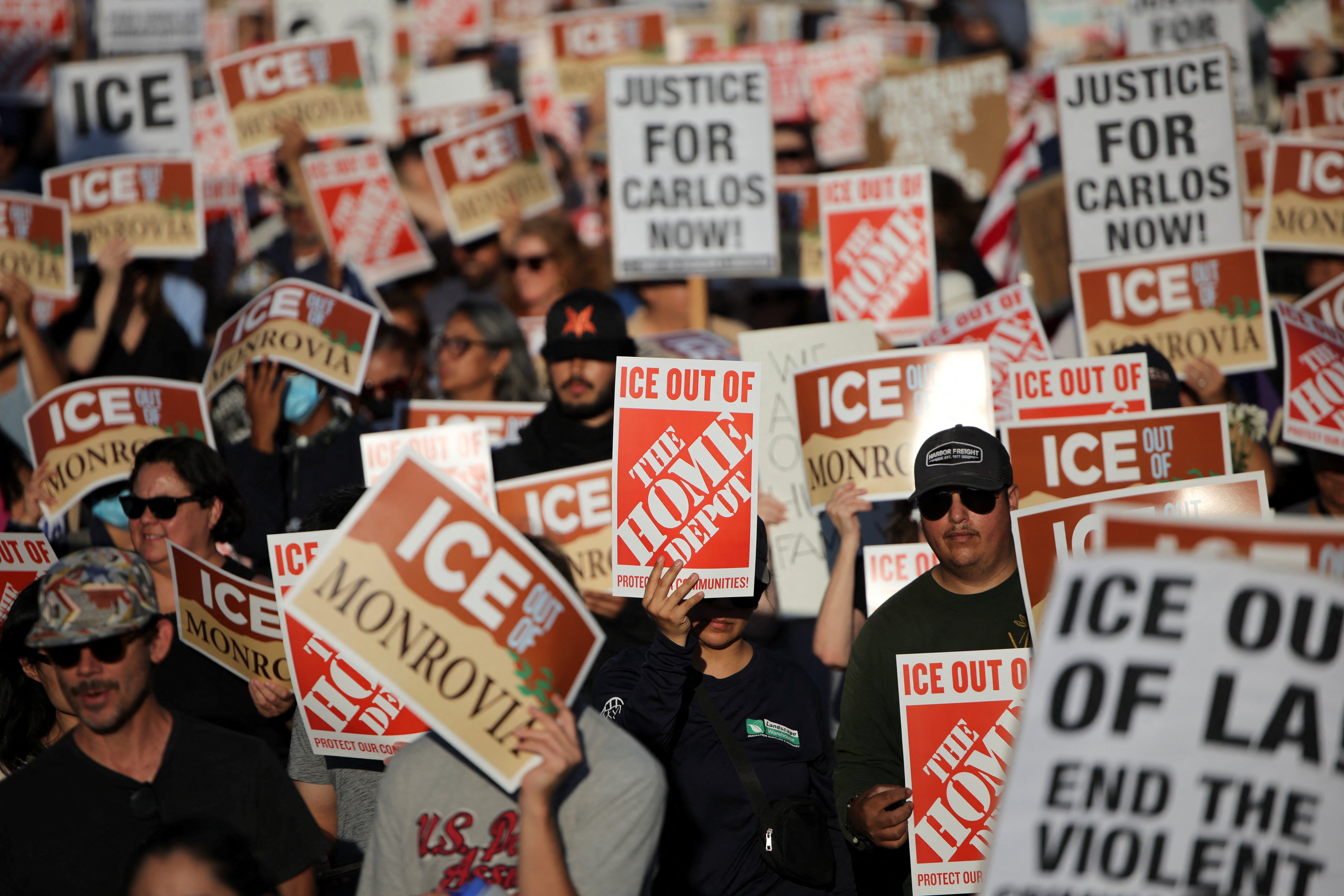

Then Trump’s second term began, and the consequences were so much worse than they’d all imagined. José and Claudia stopped going out as much. They checked the apps every time they wanted to grab milk from the store.

And then reports started coming in of people attending their legal, arranged appointments with ICE and USCIS and being arrested. People were being taken into custody at green card interviews or when they went to attend immigration court. American citizens were being jailed and held in ICE immigration raids in California. No one seemed to be immune: a 71-year-old woman was handcuffed by ICE agents in San Diego at a court hearing; a pregnant woman was allegedly wrongly arrested and assaulted by ICE officers, causing her to go into early labor; hundreds of undocumented Venezuelan migrants were arrested, put on planes, and transferred to the El Salvadorian mega-prison CECOT, despite the vast majority of them never having committed a crime.

“The most scary thing is, if something happened to us — if they arrest us or something — we can die,” says Claudia, “because [José] is diabetic. They don’t care. They don’t care if you have medicine or not. They don’t tell you where you’re going… They just arrest and keep you. That makes us very, very scared. My husband and I, we are scared.”

The family has now decided it isn’t worth the risk to even apply for José and Claudia’s citizenship. A court date or an interview with ICE isn’t worth dying for. Instead, they have decided to move to a third country, which they don’t want to disclose publicly. But even flying out of the country from a California airport comes with its risks, so they’ve spent their remaining funds on employing an immigration lawyer to escort them onto the plane and intervene if anything happens. Every step of the way is paved with fear.

“One of the things that we talked about when we started making this decision was that my dad, for the first time ever, was monitoring how much my mom could leave the house,” says Ines. “And he himself was like: I’m not gonna leave the house much at all anymore.” A couple of weeks ago, the couple had a minor falling-out before Claudia — who now drives taxis for a living — went to work. She switched her phone off for an hour, and when José rang the taxi firm to check in on her, they mentioned that she hadn’t been seen for a couple hours since she dropped off someone in an immigrant-heavy neighborhood known for recent ICE raids. José called Ines, who tried to contact her mother and couldn’t. They drove to the taxi firm’s headquarters together, Ines sobbing, convinced she might never see her mother again.

“I was bawling, crying,” says Ines. She begins to cry again as she remembers the fear that she and her father felt. “I was like: How do I find out where she is? And I realized in that moment, there’s no way to know where they took her. If they just take your family member, I was just like: How the hell do I find out? I need to be able to call a place or a number or something, or someone, to be like: Where’s my mother?”

Eventually, Claudia returned to the firm’s headquarters from her latest trip, safe and sound. José and Ines ran up to her, saying, “You can’t do this to us again — we thought you were kidnapped.” Ines describes it as “one of the scariest moments I’ve had in a long time.” Somehow, over the past few weeks, this has become their reality. “And I think sometimes it feels like it’s not or something — we can live day to day and we laugh and, you know, we’re still people,” she adds. “We go to the store and we have our jokes. We hang out. It was my birthday yesterday, so we celebrated together. And we have so many moments of joy, but the reality that we’re living under is like, if we can’t reach my mom for an hour, we think that someone’s literally going to kill her because she’s an immigrant.”

It’s a sad way to live out your golden years, says José: “We gave so much to this country. We worked very hard all our life here… So it’s not fair for us to live with this fear. Every day we watch the news and it’s just the same things, negative things. Poison things.”

It will be difficult to leave America. José says that he loves the country; that he’ll miss their block, their friends, the neighborhood where they raised their children. But now Alejandra has left with her husband to live in Greece, uninterested in staying in a country so alive with anti-immigrant fervor. And Ines is staying in Los Angeles for now, but she imagines she’ll soon follow her parents. “I just need a moment,” she says, “before I leave my life behind. I’m like: I will go meet you, I just need a second.”

Between the two sisters, they’ve saved up enough money to pay for their parents to live for a year and get settled in their new country. After that, the future remains unsure. José and Claudia own no property. The furniture they have will be donated to other family members who are arriving in the U.S. What they can sell to go toward their living expenses, they will over the next couple weeks. They will arrive at their new home — via a “very specific route” that they’ve worked out with the lawyer, one that’s less likely to get them flagged by ICE at the airport — with “seven or eight suitcases,” all that’s left of their time in United States. A friend of the family, based elsewhere in the state, is running a GoFundMe to cover some of their expenses.

“You fall love with a country,” says José. “For so many years, we were over here. And it’s difficult to say goodbye to everything, the street, you know, everything. And to start thinking about another culture at this age — it’s hard. We try to be positive.”

“I feel so protective of them,” says Ines. “And so I put on a really strong front. But the truth is that we were displaced in actually a big way because of a US-funded coup in our country. And things got really hard in Chile, and we came here literally because of US dollars and US intervention in our politics and to be pushed out this way… I’m just angry.” She thinks of what her parents went through, knowing that they were making a decision that would likely mean they’d never see their home country again, knowing that they were giving up a lot of their freedoms in order to build a better life for their children. The future they imagined, when they crossed the border in 1989, was so different.

If they’d known that this was the direction America was headed in when they crossed the border 36 years ago, I ask José and Claudia, would they have made the same decision? Both of them answer immediately: “No.” They never would have come to the United States if they’d have known. They would have left Chile, but they would have immigrated somewhere else.

There is a sense of empowerment in choosing to leave, says Ines: “It’s just like: No more, you can’t terrorize us anymore. We’ve already been living in fear.” Pre-DACA, “it was so scary for me,” she adds. “I was undocumented. It was horrible. It was super xenophobic here. Cops used to just stop us because of profiling, it happened to us many times. And my dad saved me once from a cop, because I didn’t have any identification. My dad lied and said I was younger than I was.” And these days, “it’s so much scarier… Now there’s no pretending. It’s so open: ‘We want you dead.’ It’s so clear, it’s so racist, it’s so xenophobic… So it does feel somewhat empowering for us to say: No, we’re choosing a different life.”

There are some small but important positives. For almost four decades, José and Claudia kept their heads down, worked and grinded, didn’t let themselves think about the future beyond the day-to-day. But once they leave the U.S., “they’re not trapped anymore,” says Ines. They’re going to be free to travel the world. “My dad was just saying he’s going to take my mom to Italy to see this bridge that he always wanted to, since they met over 40 years ago.”

“Living with the stress every day is not good enough for us,” says José. “It’s not good. No, no way. No, I’m tired.” He knows that the future won’t be easy. He knows things didn’t work out how they planned. He knows that even the exit route is mired with possible danger. But it will be nice, he says with a smile, to “be free”.

The names of José, Claudia, Alejandro and Ines have been changed to protect their identities. A GoFundMe is being run for the expenses surrounding their self-deportation, which you can contribute to here