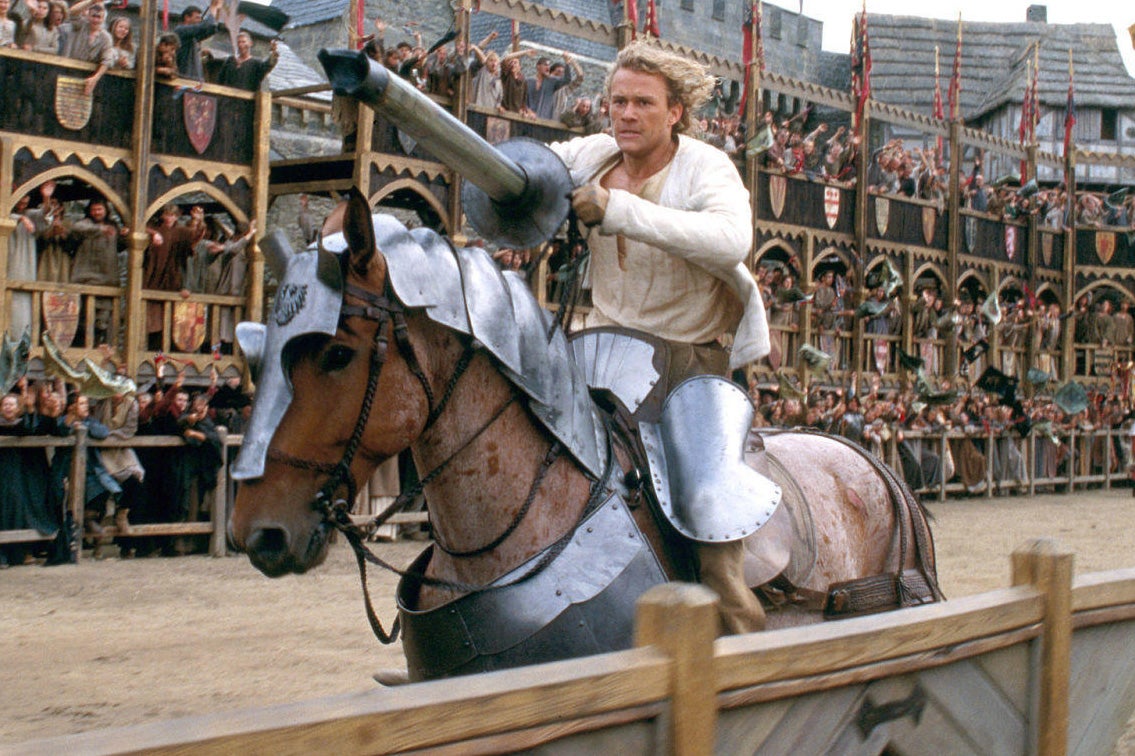

Did anyone really need a medieval jousting movie scored to Queen and David Bowie? No. Did millennial audiences in 2001 immediately understand that Brian Helgeland’s A Knight’s Tale – out again in cinemas this week – was exactly what they wanted anyway? Absolutely.

Five years after Baz Luhrmann had proved that modern soundtracks could electrify period texts in Romeo + Juliet, Helgeland applied the same logic to tournaments in the Middle Ages, and discovered it worked brilliantly. For this is a film so joyous and free of pretentiousness that questions about historical accuracy splinter on impact.

Part of the film’s pleasure is indeed how gleefully it flaunts every bizarre, lurid anachronism: peasants hammer wooden stands to “We Will Rock You”, courtly balls pivot to Seventies disco, and the whole thing vibrates with a classic-rock swagger that feels bracingly alive. Heartwarming, too. Tingeing it all with bittersweetness, of course, is Heath Ledger’s wonderful lead performance, shot seven years before his death in 2008. The film preserves his beauty in permanent youth.

In many ways, A Knight’s Tale is a time capsule from a very specific cultural moment. The story of a peasant squire who seizes his destiny landed at a point when Pop Idol had reduced stardom to a phone-in vote and the right sob story; when The Strokes had every alternative kid in drainpipe Levi’s and battered Converse thinking they could transform themselves through nonchalance and the correct haircut.

What the film instinctively gets – and what millennials understood right back – is that reinvention isn’t about lying. It’s about performing a role so completely that the performance becomes the reality. William Thatcher doesn’t pretend to be a knight; he decides he is one, then commits. Beneath that surfer hair, he moves like nobility and talks the same way.

Confidence becomes truth – it’s the same logic that powers Gatsby’s rebranding, Don Draper’s assumed identity in Mad Men, and Julien Sorel’s social climbing in The Red and the Black. Helgeland applies it to the stratified ranks of 14th-century feudalism, and makes anything seem possible. If a peasant can become a knight through self-belief, why can’t a medieval movie have a soundtrack with synthesisers and guitar riffs?

Ledger and Paul Bettany are the film’s twin engines, both operating at maximum charisma. Ledger plays William with courtly grace despite the beach-blond tangles, spouting lines like “Perhaps angels have no names, only beautiful faces” as if Jocelyn’s reaction is the only thing in the world that matters.

Ah yes, Jocelyn. Played by Shannyn Sossamon – whom the casting director, Francine Maisler, discovered DJing Gwyneth Paltrow’s birthday party – she’s the hipster pinup with whom William is smitten. Watch Ledger’s face light up around Sossamon, around his co-stars, around the audacious silliness of it all. Bettany’s Chaucer – first appearing naked, trudging through the countryside having gambled away his clothes – struts through the film like he’s already famous, a braggadocious raconteur with mischief in his eyes.

Before his first joust, Chaucer promises William: “I got their attention, you go win their hearts.” If the baroque pre-tournament hype handles the attention-getting, the “Golden Years” scene is where the film ignites. At a formal ball, William is asked to demonstrate how nobles dance in Gelderland, his invented homeland. What starts as courtly footwork suddenly shifts when Bowie’s melody kicks in and the room turns into a swirling medieval rave. The young lovers start bouncing and flailing, while Rufus Sewell’s deliciously villainous Count Adhemar glowers from the sidelines.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

It will remind you of the prom scene from another millennial coming-of-age classic, 1999’s She’s All That, only in doublets and wimples. One reviewer admitted to leaving the film “with a great big grin” on their face, and that’s the alchemy of A Knight’s Tale. It bypasses any critical faculties, heading straight for the pleasure centres where sincerity and silliness become entwined.

Roger Ebert, the celebrated film critic, called it “whimsical, silly and romantic”, noting that it reminded him “of the days before films got so cynical and unrelentingly violent”. The cast back this up: Mark Addy’s Roland makes tunics from tents, Alan Tudyk’s Wat promises to “fong” his enemies, Laura Fraser’s Kate stamps her armour with a Nike swoosh. In one scene, they assemble a love letter together from the wreckage of their broken hearts, and somehow it doesn’t feel sickly sweet.

Weighed and measured, this is a movie that runs on innocence and uncut charm. Like its star, it will forever radiate warmth.