But for Pep Guardiola, Michael Carrick might have been a triple Champions League winner. A Manchester derby is a meeting of deep-lying midfielders of different generations.

Carrick was more Spanish-style schemer than a traditionally English box-to-box bustler. He attracted an admirer in the man who will be in the opposite dugout on Saturday. In 2017, Guardiola called Carrick “one of the best holding midfielders I’ve ever seen in my life”.

Yet there might have been more recognition for Carrick’s talents but for Guardiola. He played, and scored in the shootout, when Manchester United beat Chelsea in the 2008 Champions League final. In 2009 and 2011, they met Barcelona. They were out-passed, out-manoeuvred, outwitted.

Carrick gave the ball away in the build-up to Samuel Eto’o’s opener in Rome in 2009. He was, he later said, depressed for two years afterwards. And yet 2011 may have been still more chastening. In the heart of United’s midfield, Carrick attempted 35 passes. In Barcelona’s, Xavi attempted 148, completing 141.

Not that it was really Carrick’s fault. If United were unable to cope with Barcelona’s passing game – and that remains arguably the best match of Guardiola’s career – they were further handicapped tactically. They were outnumbered in the middle of the pitch. Sir Alex Ferguson played a trademark 4-4-1-1. Carrick and a 37-year-old Ryan Giggs were up against Sergio Busquets, Andres Iniesta and Xavi.

There is a sense that United have never fully recovered from Guardiola’s appointment: not just at Manchester City, either, but at Barcelona. If 2008 represented a turning point in the game as a whole, it certainly did for United. It was the time when Ferguson’s brand of football began to become outdated, even if United could carry on winning in England as long as they had the great Scot. Ferguson did not have a philosophy in the way Guardiola did, beyond his insatiable love of winning. His teams had the ball but not to such extreme degrees.

Whenever one of Ferguson’s former players suggests the current United should play attacking football, with wingers and pace on the break, they are probably harking back to a time before 2008. In a more modern framework, they have sometimes been forced to become a counter-attacking team, because they have less of the ball; in turn because teams like Guardiola’s have more of it.

Ole Gunnar Solskjaer’s revival project was closest to the spirit of Ferguson, and had some success against City: but playing on the break. It wasn’t the front-foot, dominant football United used to play. And if one of the reasons is that, arguably, United have never really replaced Carrick, never found a distributor of his class to anchor the midfield, at times an entire club has been stuck in the past.

There have been some attempts to escape it, whether with Louis van Gaal’s dull possession game or Ruben Amorim’s inadequate 3-4-3. United tried to counter Guardiola with his old foe Jose Mourinho, without realising the Portuguese’s gameplan had become anachronistic in the days when the Catalan shaped footballing theory. They had David Moyes, Ferguson without the flair in his two banks of four; they had Erik ten Hag, who is Dutch but whose football is less of the stamp of Johan Cruyff than Guardiola’s.

A problem with an identity rooted in Ferguson’s time is that, as the game moved on and United struggled to, the goals have been more infrequent. United scored 86 league goals in Ferguson’s last campaign; they have not topped 73 since and bottomed out at 44 last year. For Guardiola, the low was 72 last year; his City have twice topped 100 and bettered 90 in three more seasons. Carrick is walking into United’s wider struggle to determine what they are and can be, while some forever talk about what they were.

Meanwhile, City are less fixated on possession as Guardiola has evolved. They have averaged a 58.9 percent share this season, their lowest in his reign. They have played more on the transition, signed more runners; Antoine Semenyo, who was a United target, is the kind of fast winger who seems in keeping with Old Trafford traditions. But now City have far greater pulling power.

Even as the age of Guardiola – both as the dominant footballing influence and as the City manager – may be nearing an end, United still seem no nearer to finding an answer to it. A gulf has grown: even as City had an off-year last season, they still finished 27 points ahead of their local rivals.

The supposed superpower rivalry of Guardiola and Mourinho has given way to the Catalan facing a series of United managers: Carrick will be the sixth to take him on. Guardiola may be relieved United did not appoint Solskjaer, his unlikely nemesis, but Amorim won as many as he lost and Ten Hag beat City in an FA Cup final to prove that, even when United have won the battles, City have been triumphant in the war.

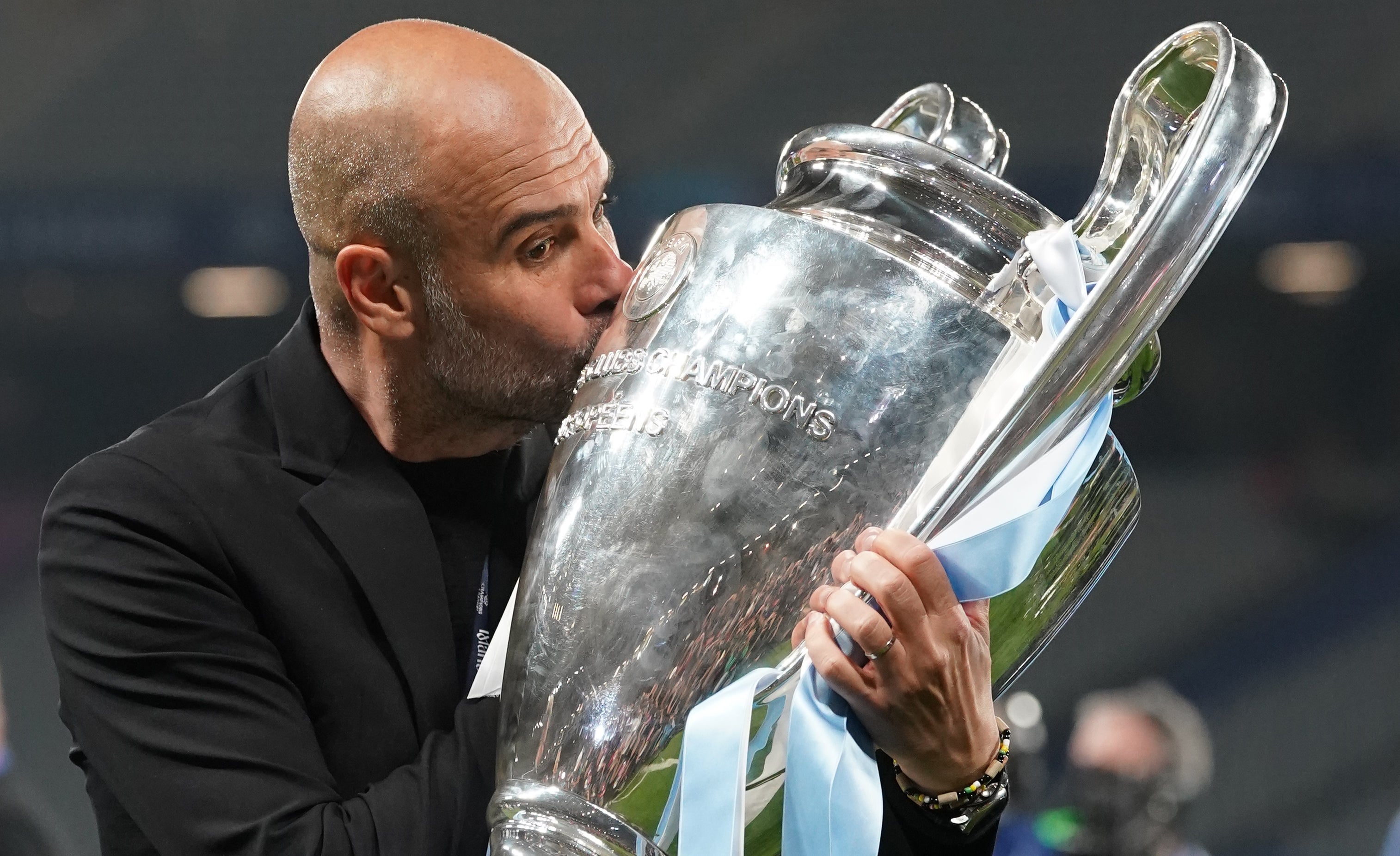

Carrick is United’s latest general but, if Guardiola sees out his City contract, probably not the last he will face. When the Catalan retires, the 2011 Champions League final will provide irrefutable evidence of his greatness. It may long remain the last time United played in one.

But if this proves Carrick’s first, last and only derby in charge, United’s search for his replacement is not merely Jason Wilcox’s quest to find a new manager. Amid talk of Elliot Anderson or Adam Wharton, they still need to unearth a belated successor in the midfield.