A recent measles outbreak in West Texas triggered a dramatic surge in school absences, far exceeding the number of children who actually fell ill, a new study reveals.

The disruption was largely due to students being excluded or kept home by their families as a precaution to curb the disease’s spread.

According to a preliminary Stanford University study, which has not yet undergone formal peer review, absences in the Seminole Independent School District – a system at the epicentre of the outbreak – soared by 41 per cent across all grade levels.

This figure is compared to the same period over the previous two years, highlighting the significant impact on student learning.

The findings offer a stark glimpse into the wider consequences of measles, a highly contagious disease that has seen a resurgence in US communities with low vaccination rates.

Nationally, and in Texas, approximately two-thirds of measles cases have been identified among unvaccinated children.

Public health officials typically respond to outbreaks by excluding unvaccinated students from schools.

Thomas Dee, a Stanford economist and education professor who co-authored the study, noted: “The costs of that absenteeism are just not among the sick kids, but all the kids who are kept out of school as a precaution.”

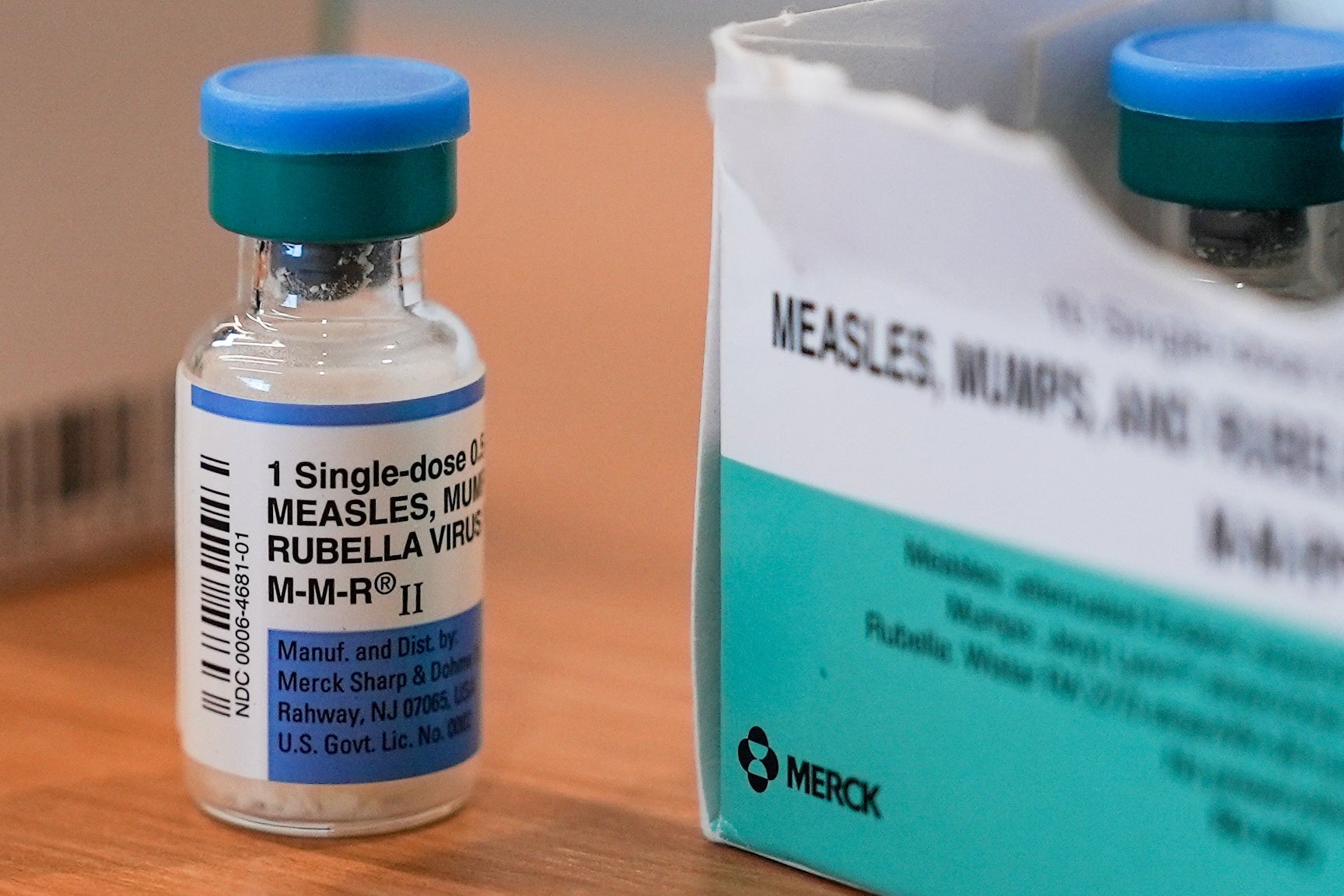

Measles, an airborne illness, poses severe risks, particularly for young children. While the disease was declared eradicated in the US in 2000 thanks to widespread uptake of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, recent years have seen an increase in parents seeking exemptions from school vaccination requirements.

Consequently, most states now fall below the 95 per cent kindergarten vaccination rate experts deem necessary to prevent outbreaks.

In Seminole Independent School District, only 77 per cent of kindergartners were vaccinated against measles in the 2024-2025 school year, according to state health department data.

The measles upsurge there launched the United States’ worst measles year in more than three decades, sickening 762 people across Texas in seven months.

That number could have been even higher, as the Texas Department of State Health Services says there were an additional 182 potential measles cases reported in March 2025 among children in surrounding Gaines County that the state excluded from its count due to lack of information.

Absenteeism extended far beyond confirmed measles cases

The study estimated, based on state data, that 141 Seminole district students had confirmed measles cases.

It found the increase in school absences was approximately 10 times what would be expected from just those students.

State health officials recommend that people sick with measles or suspected measles isolate at home until four days after they get the telltale rash. State guidance calls for unvaccinated or otherwise vulnerable students to be excluded from school for up to 21 days after exposure to measles.

Children from preschool to first grade had the most pronounced spike in absences — a 71 per cent increase from the last two school years, according to the study.

Most student absences amid the outbreak were due to local health requirements for children to stay out of school if they may have been exposed to somebody diagnosed with measles, Seminole Superintendent Glen Teal said in a statement.

Beyond the students who were directed to stay home, it’s unclear how many families may have kept children out of school on their own as a precaution.

But there’s a good argument that parental concern played a role, said Jacob Kirksey, a Texas Tech University education policy professor who was not involved in the study but reviewed it.

“If you’re hearing on the news or you’re seeing that there is just an illness outbreak more broadly, the parents are going to be predispositioned to just be more hesitant to send their kids to school,” he said.

Other states with outbreaks see many kids miss school

Outbreaks in other states, such as South Carolina, also have produced spikes in school absenteeism.

More than 165 people — including 127 students from three schools — were in a 21-day quarantine as of Tuesday because they were unvaccinated or otherwise vulnerable to getting sick.

Some children have been quarantined twice due to new cases, said Dr. Linda Bell, state epidemiologist for the South Carolina Department of Public Health.

“Vaccination continues to be the best way to prevent the disruption that measles is causing to people’s education, to employment and other factors of people’s lives in our communities,” Bell said.

Missing out on learning time can have long-term implications for a child’s success. Schools have been dealing with learning loss from the COVID-19 pandemic, which contributed also to elevated rates of chronic absenteeism.

More frequent absenteeism also puts a strain on teachers’ ability to educate their students. Most educators aren’t trained on how to handle instructional pacing when a large chunk of their students are absent, Kirksey said.